A few months ago, I met… let’s call him a gentleman of transgender experience, shall we?

Not a particularly unusual experience, in and of itself, except that this fellow was a couple of decades post-transition and deeply, deeply stealth. Only out to his family—and now, somehow, me—this fellow was a gentle, tender soul who felt deeply and had lived through things I could only imagine.

We talked for a long, long while.

He told me about his struggles transitioning around the turn of the century. Of the profound transmasculine erasure that had told him—a man who’d known he was a man from an incredibly young age—that transition was a thing only for trans women, not people like him. How it’d held him back for so, so long.

How, when he’d finally began to step into himself properly, the very transness that he’d fought so hard to gain access to was used as a weapon against him again and again. Sure, by cishet people. He expected that.

But what really stung was when queer folks used it against him.

And what wounded him was when trans people had used it against him.

When queer and trans people had threatened to out him—and in some cases had actually done so—to strangers again and again and again, against his express wishes.

It wasn’t exactly hard for me to understand why this fellow viewed his transition, his transness, as a medical event, no matter what it meant to other people—and he was adamant about that part, that it applied only to himself, and that everyone else had the right to define themselves and their gender how they saw fit. How he had chosen the deepest form of stealth when he’d finally had the option, and had guarded his history so closely and fiercely.

Betrayal like that, and especially betrayal by people who should know better, who’ve lived all of the reasons not to do what they did—it’s a terrible trauma, and one the mind and heart learns to guard itself against at great cost. My friend had made choice after choice to protect himself, each of them completely understandable and rational and sensible as an immediate response to what had been done to him, and continued to guard his boundaries and minimize the part of him that had been what he saw to be the cause of this terrible trauma: his transition. He cut himself off pretty completely from trans community to, as he saw it, protect himself from the people who didn’t see him for himself, as a whole person, with needs and history and tenderness inside that deserved gentleness and respect.

But as he unburdened himself to me in this torrent of obvious relief, something else became increasingly clear, and it was clear almost from the first moment after he’d come out to me: I’m a stranger. If he’s so deeply closeted, why was he coming out to me? Why was he sharing this part of himself with me, yet another trans stranger who could, given his past trauma, betray him, as so many others had?

And why, given that history and given his desire to be, and remain, stealth, was he so plainly desperate to connect to a trans person in this way?

So we kept talking.

The finish line…?

At the beginning of 2023, I was struggling. Part of it was coming to terms with the fact that I was still feeling top dysphoria after my first top surgery, but the larger part was something I was very surprised to discover—I was within a couple of months of the end of my transition, and found myself filled with a growing, and deeply unsettling sense that amounted, more or less, to what now?

My therapist firmly commanded me to find trans folks who had been in transition for much longer than I had, and who I could look up to as mentors, or at least as examples I could learn some of the answers to that question from. Relatively new to Mastodon, I started looking and was surprised and delighted to find several trans folks who’d been in transition for a long time. CJ Bellwether, for instance, who I’ve talked about before on Stained Glass Woman, Cait, the Canadian activist, and a series of others. It was wonderful to really connect with folks who’d made it, and who could give me an idea of what life after finishing transition could be like.

They gave me hope. Excitement.

I realized after a while that there were really only two groups of trans elders I could find. The first, like CJ, had transitioned long ago, but had never left the front lines of the fight for trans rights. They fought tirelessly for us in countless ways.

Then there was the second group: people who’d been living in deep stealth for years, for decades, and who had only recently returned to the community, effectively coming out for a second time as trans. One after another, they’d eventually talk in some detail about why they’d decided to rejoin the community and be public about being trans. Many of them talked about community and the importance of self-identity. Many of them shared incredible details about the realities and struggles of their transitions.

And a lot of them talked about how much it had hurt them to live in stealth.

It was a real sea change for me, to think of that. I’d never thought I’d be gendered correctly on a regular basis when I entered transition. I planned from the get go for it, telling my wife that I’d be a “crossing-guard,” the visibly trans woman there to protect everyone else because I was safe being myself. I’d always lived very, very out, in that expectation. But, by the winter of 2022, it was pretty clear that that didn’t have to be my fate if I didn’t want it to be.

I’d never thought of living stealth before… and listening to my elders was giving me pause. Serious pause.

What if going stealth could be just as traumatic as living in the closet? Not for everyone… but for a lot of us.

History, oppression, and exclusion

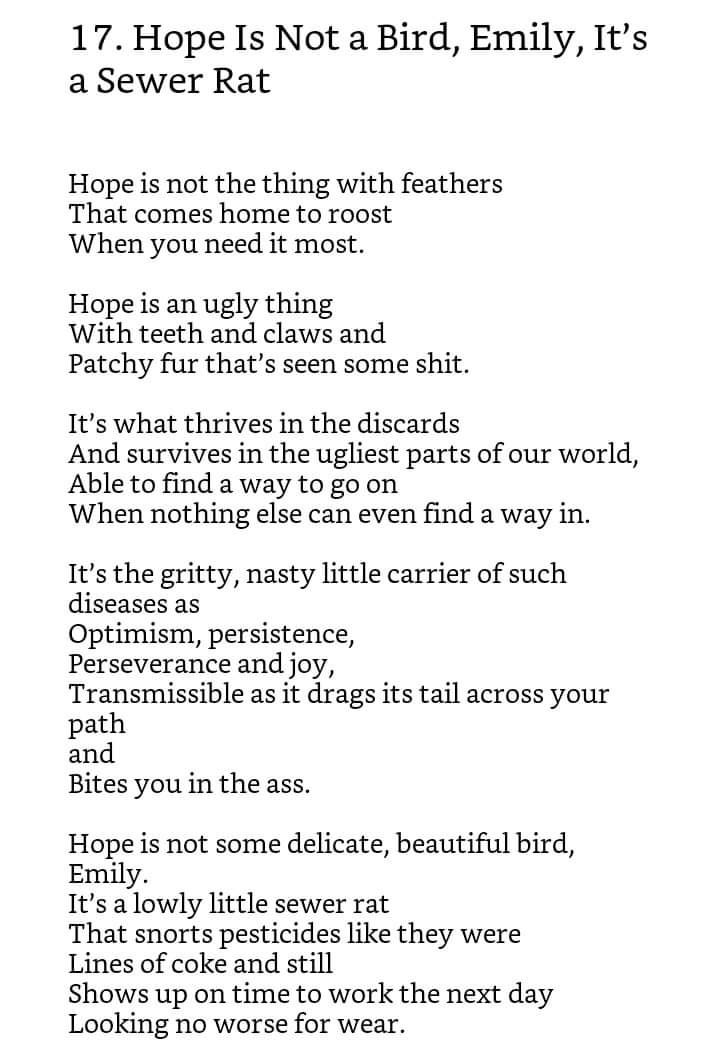

Maybe one of the most important pieces of homework I think every trans person needs to do when they either come out to themselves or enter transition is to read Susan Stryker’s Transgender History. It’s a hard book, in many places. Brutally hard in some. Our history is not one of triumphs, of battles fought and won—it’s one of survival, grim determination, and hope in a form that Emily Dickinson would never recognize.

One important part of this history, however, is the history of what we were required to do in order to gain access to gender-affirming care. To transition, often, at all. Stories of men fighting tooth and nail to get the testosterone they desperately needed, writing therapist after therapist after therapist to no reply, ignored and erased by a medical establishment that had no interest in their existence. Women, walking San Fransisco’s Tenderloin district, selling their bodies to afford the estrogen, and the surgeries, that were saving their lives.

Those fortunate few who made it through all the hatred and oppression, who were deemed by skeptical therapists that they would be physically attractive enough after transition to be allowed to transition at all (I wish I was joking), were forced to move away to completely new places, cutting all ties with the families they’d had before, and to never speak of or acknowledge their history of transition again. It was almost like the witness protection program, except without any protection.

They had to forget their entire lives, before.

Identity, stealth and privacy

One of the things my post-transition friend talked about a lot was how even the label “trans” felt like an itchy sweater to him, something he couldn’t stand. He struggled to even find a way to talk about who he was that felt like an identity, and not a label.

Something that didn’t make his manhood feel conditional.

If you’ve ever read a word of Stained Glass Woman before, you know that my experience of transness is the opposite of his—that, for me, it’s liberatory, the key to the door that had shut me out from womanhood for my whole life. It gave me wings to soar and unchained a lonely heart to finally allow me to truly love the people who are precious to me.

But… but that sentiment? I can understand that sentiment. I’ve heard it from so many trans people of every imaginable gender, this strange and troubled love/hate relationship with a part of themselves that gave them everything they’ve ever dreamed of having with one hand and punished them brutally for taking it with the other. Even captured in the way we used to say trans—the hanging asterisk. A footnote to who we are.

Conditionality.

It’s a sentiment that comes up so commonly in discussions of what-comes-after-transition that it’s hard to find conversations that don’t include people explaining how they love being their gender and kinda-sorta-hate-but-kinda-not being trans. It’s a sentiment I’ve seen in some of my close friends, who could go stealth if they wanted, and who have even toyed with the idea and the desire to do so, but have never quite been able to. Something about their transness keeps drawing them back, drawing them out.

Reaching for connection, like my gentleman friend so desperately was, despite his many hurts.

The thing about identity is that it’s arbitrary. Each of us picks and chooses the bits and pieces that make us who we are and raise some up while tossing others aside. That’s normal. What can be an identity for one person can be a hurtful label for another. That’s normal too.

But.

But there’s an important difference here between being stealth—actively and proactively obliterating any trace of your transness from the world in an effort to live in a way that cis folks can’t detect—and privacy. Privacy is just picking and choosing who you’re out to. That’s inevitable.

And the thing about stealth is that it’s just another closet to hide in, from the same old tigers you were hiding from before you transitioned.

The Glass Closet

On a long enough timeline, pretty much everyone who wants to “pass”—to be gendered correctly consistently and automatically—will, no matter how impossible it seems when you take that first, impossible, dizzying step into your social transition. And, when that day finally comes, there’s nearly a century of history that tells us that what we should do is disappear, to live our lives as though we were cis, as though we’d been born in the bodies we’ve spent years, and maybe our whole lives, finally making right.

The thing I came to realize from getting to know the many other older trans folks I met when I finally went looking for them is that for trans people, unlike for most other queer people, we’re not generally just in or out of the closet. When we’re post-transition—and I am now, as bizarre as that is for me to say—we find ourselves thrust back into a closet of a different kind. No longer hyper-visible as in-transition trans people, we’re simply assumed to be cis by the people around us, erased in a whole new way.

A fractal glass closet. No matter how often you come out, there’s always another closet door, closed and waiting for you.

We’re visible and seen as who we are, sort of, but with the entire history of what was, for most of us, the greatest struggle of our entire lives just… amputated, the stump of where it once existed left bloody and raw and dripping, the wound invisible to everyone around us. Sure, for most of us that history didn’t exactly feel good, but it’s a part of who we are, and goddamnit if we didn’t do some amazing things in transition.

Now, I need to be clear: you don’t owe anyone being out and proud, the way that I am. It’s right for me. It might not be right for you. But the fact of the matter is that staying closeted has devastating effects on the mental and emotional health of trans folks, whether we are pre- or post-transition, because the act of closeting itself is a denial of our authentic selves. The fact that we’re living as our true selves now, in bodies that fit who we are, doesn't change the fact that that glass closet is still a closet, and that by fighting to go stealth, we enact the exact same minimizing emotional self-harm on ourselves that we did by staying closeted before transitioning.

There’s a terrible price that comes with that emotional and historical amputation: nobody who hasn’t been through transition can ever understand what it’s like to live the lives that we live. They can try. Well-meaning, with open hearts and kind words, oh, they can try. Many do.

But they can never understand. You have to live it.

You don’t owe anyone your identity or your privacy. Anyone. But you owe yourself the right to the fullness of your own story, to share with the people you want to share with. To be seen for a whole, complete, complex person.

To heal from the traumas of being closeted.

And that means coming out of the glass closet from time to time, for the rest of your life.

Other articles in the Grinding Glass series:

Shattered, a new model for understanding gender dysphoria.

Growing Up Broken, an examination of how trans trauma forms.

Slivers, a discussion of how we reenact our trauma on ourselves.

Complex Trauma Disorder? I hardly knew her!, which helps you walk through the process of accepting a complex trauma diagnosis.

Holding the Girl, a discussion of what healing from complex trauma looks like.

"On a long enough timeline, pretty much everyone who wants to “pass”—to be gendered correctly consistently and automatically—will, no matter how impossible it seems when you take that first, impossible, dizzying step into your social transition."

Thank you, I apparently really needed to hear that.

One thing that recently got to me is how universal can this erasure be. I come from an eastern block post-socialist country and I've learned that, seemingly spontaneously, trans healthcare used to operate in much of the same 'witness protection' way as in the Strykers' account of US history. There are trans folks alive here today who are even closeted from their own biological children. Another example would be UK, where gender recognition is conditioned on the trans persons' commitment to 'live in the acquired gender until death.'

The overriding message is clear and transcendents borders: 'Try to be cis as much as possible, and if you really really can't, transition as quickly as possible, and for christs' sake, don't let anyone see you doing it!'

Anyway, excellent piece as always!

I'm still in the middle of my medical transition, but I can see the finish line. I have two major surgeries scheduled for next year, in February and April, and unless I need revisions, I expect that will be all I need.

I don't know what to expect when this phase of transition is over, but I think my trans identity will fade into the background. It will never completely disappear - too many people know me as a trans woman, and I don't intend to abandon them. But I'm hoping it won't be a big part of my daily life. A lot will depend on how femme my appearance becomes and how completely I pass.

A lot of that has to do with how I think of my various identities. I've always wanted to be able to call myself a woman, and the label is beginning to fit. I imagine it will feel much more natural after my next surgery. I'm also a lesbian, and that label already feels natural to me, even with my medical transition still incomplete. And I'm *enthusiastic* about those two identities. They're things I've wanted my whole life, and I've known I wanted them for a long time, even if I couldn't acknowledge that until fairly recently.

I'm not enthusiastic about being trans. It's an important part of who I am, and I'm proud of that, without any shame, but it's not *important* in the way that being a woman or a lesbian is. I'll always be publicly out and part of the community, but if the average stranger can't see that I'm trans, that's fine.

We always say trans women are women, period. But I don't feel like I am right now. This trans woman is a woman, asterisk. I'm looking forward to the day when that's no longer true.

I do realize how privileged I am to be able to transition today, without all the nonsense required of trans women in the past.

As always, thank you for sharing your experience.