A couple of years ago, I was in Colorado visiting my sister. We’d had a great time—camping, cooking, stargazing, playing board games, shopping—so, on the morning my wife and I were heading out of town, the three of us decided to grab breakfast at a nearby diner. While it wasn’t quite a properly rural greasy spoon, it was pretty close—on the far outskirts of the sort of suburb where houses front on fields. After all, we’d been camping. Nobody wanted to drive a half hour into the city just to drive back out afterward.

So, my wife, my sister, and I rolled into this diner. This darling of a little late-middle-age lady bustled the three of us to a table in her section and cheerfully asked what had brought us in. I told her that we’d been camping and were having breakfast with my sister, gesturing at C—, before we left town. Of the three of us, my sister was the only person who’d had a shower in the last couple of days. My wife and I, smelling of campfire smoke and with little more than wet nap wipes to keep us decent for public were, to say the least, a bit disheveled.

The server smiled and seated us, looked at me, then my wife, then back to me, and asked, “What can I get you and your husband for drinks, honey?” I blinked, looked over at B—, then back at the server.

“She’s my wife?” I replied, sure the server had clocked me, but she’d been looking right at me when she’d spoken.

Instead, she started, looked at B— in surprise and said, “Oh my goodness, I’m so sorry!” I sat there in stunned silence as B— ordered drinks for us; my cisgender wife, who has a rather significant bust and very prominent hips, had been misgendered by this little countryfied server while I’d been gendered correctly. At the time, I was barely a year into my transition and I couldn’t believe it. Forty-five minutes later, as we got up to go, the server pulled my wife aside to apologize again for misgendering her.

We drove away from the diner and toward the next stop on our road trip, and about ten minutes after we got onto the freeway, I turned to B— and asked, “What the hell just happened in there?”

The science of gendering

How we gender someone—meaning, how we guess at the gender of an unknown person—is, it turns out, a pretty weird and messy process. Because of that, it’s something we’ve been studying for a long time, and for a lot of reasons. In particular, it’s useful in neurology to study how the human brain performs something called heuristics, which is the process of using cognitive shortcuts to get to an answer in far less time than we’d need to make a decision if we really went through the whole pro/con decision tree process that we use for conscious decision-making. It’s a really important area of study because, among other things, it’s how we’re able to make split-second decisions that can save our lives in a pinch. Beyond that, it also dives deep into how stereotypes and bigotry are formed and reinforced, which is, as you might guess, an increasingly-important area of research these days. Ever taken one glance at some sketchy food from the back of the fridge and noped right out in a split second? That’s heuristics, saving you effort and trying to keep you safe.

These days, a lot of the heavy lifting of this research is done with brain scans, and especially fMRIs. These tools let doctors and researchers watch the brain as it lights up with a decision-making process in real-time, and lets us record each fraction of a second as it does, for analysis later. From these brain scans, we’ve learned a whole bunch of things about how people gender folks.

As a note before we dive into the meat of the data here: as with almost everything, nonbinary genders are desperately understudied in the science of gendering, to the point that I could find no significant research on the gendering process which was inclusive of nonbinary identities. This is wrong. It is evil, in my opinion. But I can’t report on data that doesn’t exist, unfortunately.

First: Gendering happens fast

It turns out that it only takes between 100-300 milliseconds to gender someone we don’t know. For reference, that’s the literal blink of an eye, start to finish, or less than half as much time as it takes for us to receive sensory input, like seeing something, and form a conscious reaction. That puts the gendering process squarely into the realm of the subconscious, meaning that there’s no actual decision-making involved in it, just heuristic instinct. Now, the brain is an incredibly powerful computer (even if it is made out of meat), so it can do a lot lot lot of work really quickly, but it still uses electrical and chemical reactions to do its thing. Thinking, in other words, takes time.

Second: It’s almost all about silhouettes

When someone’s having that blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment where they gender an unknown person, 80% of the information a person uses to gender that person comes from the fundamental structures and shapes they see. When scientists say that, what they’re saying is that bits and pieces like the shape of a person’s hair, their brow, the shape of their jawline—stuff like that—are what people are seeing. People assemble a best guess at a person’s gender by piecing together some shapes that they’re seeing at a glance into a whole. Moreover, social context clues are really important—often more important than physical structures!

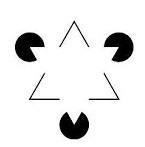

This is the basis for a school pf thought in psychology called Gestalt psychology, but you’ve probably run into the core idea underneath it in art class, where your teacher talked about Gestalt as a design or artistic thing. In a nutshell, it observes that people recognize the whole of a thing from a collection of parts which are much less than that whole. It’s why, when you look at this picture…

…you see two triangles, not some random lines and circles. The same basic thing is happening when we gender someone based on a glance at their face or body—we see rough bits and bobs, and take a subconscious guess before the full information gets in.

Third: People have Big Problems when they perceive conflicts

Because of how gestalt works, when a person—especially a man—sees a face that they would gender one way and hear a voice they’d gender the other, they report real distress. That mismatch causes people to think much more negatively of the person they’re gendering in all sorts of ways, and this cognitive dissonance can lead to outbursts of violence. Anyone who’s struggled with voice training will have noticed this effect themselves, and it’s a big part of the reason that voice feminization surgery exists.

The upside of this is that when a voice “matches” what the person gendering expects for a face, the strength of their confidence in gendering them rises a lot. Gendering is quick and messy, remember, so information from a different source that reinforces what a person is guessing has an outsized effect.

It is for this specific reason that I won’t be offering suggestions in this article for ways to achieve gender confusion or high androgyny, as many nonbinary people work hard to achieve. With enbies understudied in general and the only data we have pointing towards potential danger, I’m worried that I might make a suggestion that could get someone hurt. It’s not that those goals are not legitimate and worthy—I just don’t know how to point someone towards achieving them safely.

Fourth: When in doubt, people tend to guess “man…”

Almost every piece of research what looks at how we gender people has found that when in doubt almost at all, people guess “man,” and this effect even happens when people gender voices from audiorecordings. Many people argue in the tradition of de Beauvior that this is because women in the West are culturally “marked” by the ways that they are not men—that, ultimately, this happens because women categorically are subjugated by men. There’s not a lot of good science to support this argument. Now, that’s not to say that patriarchy isn’t a thing, and that women aren’t subjugated by men—just that it probably isn’t that simple in this case.

A good social psychological counterargument would be that in the West in the 1800’s, women were very forcefully shoved into the home and out of public life, and that it wasn’t until the 1960’s and 1970’s that we re-entered public life in a meaningful way. After almost 200 years where, when you met a stranger on the street, it was overwhelmingly likely to be a man, that perspective would argue, undoing that bias at a macro, cultural level is going to take a long time. Same general point de Beauvior was making, but more of a question of logistics than philosophy.

I tend to agree with the social psychological argument there, because…

Fifth: …and men are much more likely to guess “man” than women

Look at any of the studies I linked in the last couple of paragraphs and you’ll see a note in every abstract that women are a lot more accurate at gendering unknown figures and voices than men are. Not infallible, for sure! But between eight to ten percentage points more accurate is pretty common among findings from study to study.

This is why I tend to buy the social psychology argument above other theories I’ve seen—men are primed to expect to see and meet other men in public and on the phone, so they guess “man” much more often than “woman” when they’re in doubt. Women, who were exiled to the home and saw a more balanced split of men and women during that time period, are more accurate.

Sixth: We know exactly what cues people to gender a face

And the number one thing is the shape and style of your hair. No joke. A good haircut and the right hair care dwarfs almost everything else. Beyond that, in order of most to least significance, here’s what goes into gendering a face:

Brows (inclusive of eyebrows plus brow bone)

Eyes

The jawline as a whole

The chin by itself

The nose and mouth in combination

A person’s nose by itself and ears by themselves didn’t have any effect on how a face was gendered. But here’s the cool thing—they also studied how a face can be shifted from being gendered one way to the other, and the order is different! By changing facial features, again in the order of most significant to least significant, this is what changes can be made to a face to change how it’s gendered:

The jawline as a whole

The brow and eye, as a combined block

The chin by itself

Brows alone (inclusive of eyebrows plus brow bone)

Interestingly, changing the nose and mouth block in a face didn’t affect how people gendered a face at all, and noses by themselves and ears by themselves didn’t change anything either.

Whatever, nerd. How do I get gendered correctly?

Well, the first bit you need to accept that you’ll never be gendered correctly all the time. Ever. And that if you’re transfeminine, you’ll be misgendered more often than you will be if you’re transmasculine.

Let me be clear here: this reality has nothing whatsoever to do with you.

Gendering is a fast and messy cognitive process, which means that it’s going to be wrong sometimes. Ask any cisgender woman, even one with a pixie-high voice, when the last time she was misgendered on the phone, and the answer you’ll get will rarely be more than a year ago.

Yes, it hurts when you’re misgendered, and that pain is very real and very valid. We fight like hell to be seen as ourselves by the world around us, and every time we get misgendered, it feels like all of that work is pointless.

It’s not. Remember: each person’s brain is a meat computer.

Wired by a drunken electrician.

On an ad-hoc basis.

It’s gonna screw up.

That being said, because gendering is a fast and messy process, there are a few things we can do to screw with it and make it much more likely to get the outputs we want—and none of these require surgery, or even hormones.

Get a good haircut

Since visual gendering is first and foremost about silhouettes, your hairstyle is by far the biggest thing you can do to change the silhouette of your head. Have a look at the two people, below, both of which have long, curly hair, just one masculine and one feminine:

Men’s hairstyles, whether short or long, tend to pull hair back, away from the face. A degree of messiness and quick-and-dirty control of their hair is really common, and can actually be a signal for masculinity. Women’s styles, on the other hand, tend to be split left-right and pulled forward. There’s a much higher priority on really good haircare, so that even with hair that’s naturally curly and frizzy, it looks carefully-groomed. Seriously, look at those two hairstyles—the woman’s hairline is higher and farther back than the man’s, and his hair has none of the classic androgenic M-shape, but you’d never guess hers as being masculine and his as feminine.

In a nutshell, men's hairstyles tend to expose the face, and women's hairstyles tend to frame the face.

If you haven’t had a gender-affirming haircut, invest in one with a stylist who knows trans hair. Talk to them about proper hair care for your specific hair type. You might be shocked at the difference it makes.

Get the right brow wax

A browline can be absolutely transformed by the right eyebrow treatment. Look at the hair picture again. The man has lower, flat, bushier eyebrows, and the woman has higher, thinner, arched brows. But, more importantly, that guy has basically zero detectable brow bone. If you’re transmasculine, and you’ve got naturally-arched eyebrows? Go get them flattened out some. If you’re transfeminine and have flat or bushy eyebrows? Get them thinned and arched. It’s cheap, and it can completely transform the look of your brow.

Tweak your body language and gait

If we’re putting together a gestalt of the body, it can’t start and end with the head, can it? Men and women tend to take up space in different ways with our whole bodies, and that body language—especially the way you walk—can make a really big difference. One of my favorite ways to see this is in animation, because animated figures deliberately exaggerate gendered behavior, in the same way they exaggerate everything else. So that we’re making an apples-to-apples comparison, I’ve plucked out a gif of two people animated by the same studio and in very similar styles (credit to Jocelyn). Check out Li Shang, from Mulan:

He plants each fot directly in front of where it was in its last step. When he moves, his arms swing from his shoulders, his elbows adding almost nothing. His elbows are further out than his hands. His hips are stable and his back is stright, and there’s a bit of a forward lean. His head stays at almost the same exact height from step to step, but rocks back and forth, left to right, as he moves. He occupies space, expansively.

Nani, meanwhile, places each foot with about a 1/3 overlap with the foot trailing it. When she moves, her forearms add much more swing to her arms than her shoulders. Her back is arched, so that by the time it gets to her neck, her spine is almost perpendicular to the ground, and her hips swivel forward-to-back with each step (not rocking side-to-side, as many people mistakenly do when they’re learning a more feminine walk—pay special attention to the side-on animation here). Her head bounces up and down as she walks, with virtually zero side-to-side sway. As a whole, Nani uses space in a much more compact way than Li Sheng.

Now, it’s important to note that gait and body language aren’t definitive! Women with balance or mobility disabilities, for example, sometimes walk more like men typically do, because it allows for better balance control in certain ways.

Clothes, clothes, clothes

The last thing you can do is something you’ve probably already done, but it bears repeating—men’s clothes tend to be baggier, and women’s more form-fitting. It’s not just a question of style here, but of fit, and that’s where a lot of trans folks misstep when they’re early in their transition. Careful measurements are really important here.

What the hell happened back in the diner

We didn’t know it then, but what happened to my wife and I in that diner was a pretty simple combination of things. First, the little old lady saw that we were touching in the ways that couples casually touch in public, and wanted to read us in a heteronormative way. Second, I had long hair that I wore swept-forward and to the left, and I was wearing a casual jersey knit dress. My wife, on the other hand, was wearing a baggy T-shirt and shorts, which she prefers while camping. She had a very short undercut, and was wearing the hair pulled up and back into a quick ponytail, because she hadn’t been able to shower in a couple of days.

In short, I was presenting in a classically-feminine way because I just enjoy doing so, while my wife, for whom camping is very much vacation and relaxation time, was dressed for maximum comfort. I fit the “woman” mold, and my wife the “man” mold in that moment, to that server.

And gendering is quick and messy.

I have often said that it is amazing just how much dysphoria one can store in one's eyebrows. Great article, as usual!

I still get misgendered all the time. I feel pretty good if I get ma'am'ed more often than sir'ed over a given week, and I live in Seattle, where people know how to override their heuristics for trans people. I'm hoping FFS can improve that ratio, but I've resigned myself to always being visibly trans. The one place where I consistently get gendered correctly is over the phone, where the only available information is my voice and (maybe) my name.

My (cisgender) wife *also* gets misgendered all the time and has since she was a child. She has a very short (but femme) haircut, and she tends to wear bulky clothes. That's all it takes for her.