Foreword: This article includes a frank discussion of childhood abuse.

“Here, put this on,” my mother says hurriedly, pressing a black beanie cap toward me. The school bus is coming, and the bright cold of the early January morning is fierce, here in Minnesota. It’s just barely 1992, and this winter has already been legendary, even among us northerners. The first blizzard came so early that we’d all had to go as skiers for Halloween a few months back.

“No,” I say, insistently. The hat has a cow pattern, which is fine if a bit embarrassing, and a ring of bright red hearts around its brim, which is emphatically not. I know that there is no circumstance under which I can allow the boys to see me wearing a hat with those hearts on it. I cannot explain what I know, or how I know it—only that it would be bad, apocalyptically bad, to a six-year-old, for me to be seen wearing this.

“Put it on. It’s cold,” my mother commands, her tone brooking no discussion. We’re in this situation because I can’t find either of my other two hats, the ones I prefer, and neither can she.

“No!” I shout with all the petulance and rage my little body can muster. I’m fighting back tears, and I don’t know why, but I cannot lose this fight. She takes the hat from my hands and stretches it onto my head.

Well. It seems I’ve lost the fight.

“The hearts…” I trail off, hopelessly. She presses her lips together and rolls the brim up, hiding them.

“There,” she says. “Now nobody will see. Now go! You’re going to miss the bus!” I’m hustled out the door, and trudge through the snow, my little legs struggling with the deep, heavy, crystalline drifts. Four boys already wait at the bus stop—my next door neighbor Eric and three whose names I have trouble remembering. They’re rowdy this morning, jostling each other and laughing.

I figure I can take my hat off and hide it in my backpack once I’m on the bus. Mom won’t see then. I won’t get in trouble.

I shuffle out of the snow and stand near them. I’m friends with Eric, but I stand just a little bit away today and hope they won’t notice me.

It works. For about two minutes.

Eric stumbles against the snowbank as he reels from another boy’s roughhousing and bumps against me, laughing in delight. He turns, grins widely, seeing his friend.

And, with one hand, bats the folded-over brim of my hat down. It slips down all around my head before I can even begin to reach up to fix it

That moment hangs in the air for me, an existential dread I’m far too young to understand overwhelming me. All four of the boys are looking right at me, the traitorous row of hearts exposed for all to see.

“Zac’s a giiiiiiiirl!” Eric shouts, and the moment shatters. All of the other boys join instantly, and this is the worst possible thing to be called, the worst possible thing that could happen to me. My young brain cannot understand why this is so terrifically bad, why it is the thing that must be avoided at all costs, but it is, it was, and—

I burst into wailing tears as the school bus rolls up.

The boys make me get on the bus first. The bus driver is a mean old woman, and she doesn’t even glance at me as I pass her, sobbing. The boys chase me to the back of the bus, howling with shouts of “Girl! Girl!” Utter delight at getting such a huge reaction from me.

I know I need to stop crying, or it’ll only get worse.

But I absolutely cannot stop crying. Something about this that I don't understand—can't understand—makes me despair in ways my little heart can't bear.

I stuff the traitorous hat into my backpack, but it’s no use. We’re one of the first bus stops, and every little boy and girl who get on the bus is egged on by those already there, joining the jeering and taunting. Twenty minutes later, we finally arrive at school, and by that time, the entire bus is shouting and laughing at me as one.

Eric never treats me like a friend again.

Neither does anyone else at school.

I will not know a single day’s peace at school for another seven years, despite two school changes afterward. Not a single friend. Somehow, they’ve unearthed something in me that every one of these students knows to be repugnant, to be worthy of nothing but mockery and derision and the most absolute hatred. In middle school, the boys devise a rota to attack me, beat me bloody, because the school has a zero tolerance policy for fighting. This way, they only get suspensions, but the school quickly gears up to expel me, despite the fact that I never once fight back. The only way I avoid getting expelled is because my parents threaten legal action against the school for not protecting me.

Even then, when I finally find a very few friends by copying, for years, the mannerisms of the boys around me until it all becomes habit, the teens who hate me vandalize my family’s home with motor oil, and one of our cars with silicone caulk. They scrawl what a pervert I am all over my home, in ways that can’t be gotten rid of without tearing out concrete.

Just to make sure I know I’m untouchable.

It doesn’t end until I flee to college. I want to flee the country, but I can't.

None of them could ever articulate what it is about me that sets them off. None of them, let alone me, as I bury everything in me that might possibly be objectionable as deep as I possibly can, could identify the queerness that they pick up on by instinct.

But they do.

Being the Other

Queer people don’t grow up as ourselves.

Each of us knows this, on a deep, deep level. Some of us even engage with it after coming out, whether as a sexual minority or as trans, and stand up to speak about oppression and intersectionality and all that good feminist stuff.

But let’s get deeper here. What does it mean, fundamentally, that we don’t grow up as ourselves?

There’s this idea in philosophy, psychology, sociology, and feminism called The Other. It was first laid out by the very famous dead-white-guy philosopher John Stuart Mill as a way of understanding the difference between how a person builds and understands themselves in their own mind and how they do the same thing for everybody else around them. Useful, sure, but it didn’t really take off until another dead-white-guy psychologist by the name of Lacan, and eventually the jack-of-all trades Derrida (yep, the panopticon guy we talked about a while back) picked it up and built it out as a way of understanding not the difference between the self and the not-self, but of social orders themselves. Othering is a psychological and social tool which allows a person to conceive as another human being as less human than themselves, and therefore someone they can act out against with no fear of retaliation.

Yeah. Things get a little abstract when Lacan and Derrida join the party.

I mention all this because in many ways, understanding Othering is the basis for understanding all of the big moves in psychology, sociology, critical theory of all kinds, social justice, feminism, queer theory—everything—in the last forty years.

So, let’s talk about it in concrete terms.

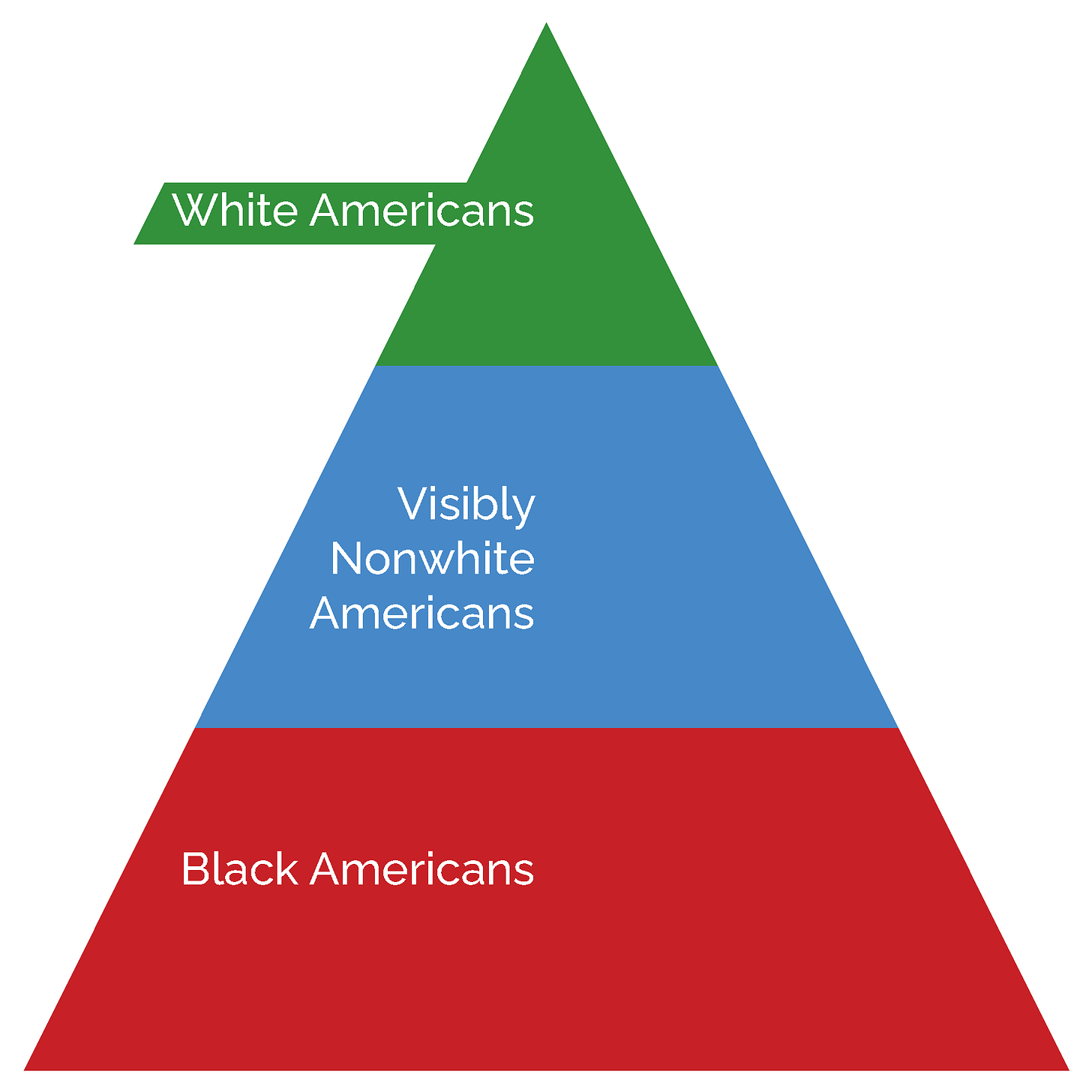

Isabel Wilkerson is one of the most brilliant people alive today when it comes to talking about race and racism, and her monumental book, Caste, argues that America—all of western society, really, but she works with data from America—is a caste system, drawing from the Indian historical term. Castes work by assigning people an inherent, hierarchical rank based on their birth, and the American white supremacist caste is an even sharper calcification of this in many ways. People at the top can act out against people below pretty much however they want, and their opportunities and social limitations are defined by that birth-reality. Probably the easiest way to understand it is as a pyramid:

The golden rule of a caste system is this: anyone on a higher caste layer can strike out against anyone below in the hierarchy and anyone on a lower caste layer may never exercise power over the people above them; any attempt to do so is and must be met with overwhelming retaliatory force. Not everyone in the system exercises this power consciously, but if you look at things like incarceration rates for Black men and compare them to white men, for instance, the differences are striking, especially given that white and Black folks commit crime at pretty much the same rates.

One person others another in this hierarchy when they exercise their power over someone lower, to make them subhuman—or, at least, less human than the person lashing out. The thing is, race isn’t the only inborn, inherent trait that people have, and which is used to other. Gender and sexuality are too, which is the whole premise of feminism. That means that that pyramid can have more detail.

A few quick disclaimers: this second pyramid is not exhaustive or completely accurate; I’m white, I’m not a scholar on race, and arguments could and should be made about model minorities, whether, for instance, straight men of a lower caste have more power than trans women of a higher caste, how people who are both gay and trans add even lower layers to each gradiation, how being disabled adds even more complexity to the whole pile, and things like that—that’s intersectionality for you, and it’s incredibly complex. The point here is to illustrate part of that complexity, so we can understand it and talk about it.

When you’re queer, being out or public at all about the fact that you're queer allows people to exercise their caste power over you. We are constantly pushed, pressured, punished to be not-ourselves, to seize the greater power that comes from living in a higher level or gradiation in the caste.

But that means that if someone can figure out that you’re a member of a lower caste and hiding it, or refusing to submit to the caste system? Oh, the retaliation is severe. But you already knew that, didn’t you? We have a whole Day of Remembrance for those of us who are murdered every year.

And, yeah. That’s why the overwhelming majority of the people we remember on TDoR are Black trans women.

Alienation and Self-Loathing

Growing up trans is a process of growing up and being told by the whole world that you are the Other, whether you know it or not, and the degree to which you’re othered is increased depending on how racialized you are. You spend your childhood watching a parade of horribles, disgusting caricatures of who you are inside. Maybe it’s Ace Ventura, whose climax shows a trans woman being stripped naked in public.

Or maybe it’s Buffalo Bill, from Silence of the Lambs, who murders women to make a skin suit from them. Not a “true transsexual,” of course, according to the show—just someone deranged, who doesn’t deserve to live as their true gender.

Or maybe the biggest crime procedural of its era spends a whole season chasing a trans serial killer, with the lead characters of the drama mocking trans people over and over.

I was a child when I saw all of these characters. Watched them dance across the screen as monsters beyond description, “rightly” rejected with profound disgust by the caste system. And, I’m guessing that if you’re trans and you’re reading this, you can look back in your own memory and find your own parade of horribles, murderers and victims and parodies of transness, all of which existed for one purpose:

To tell you that trans people don’t deserve to exist.

Stop and think about that for a minute.

What happens to a child who’s told from birth that they don’t deserve to exist?

In psychology, there are a few categories of severe psychological harm that happen as a result of needs going unmet as a child. They’re called attachment injuries, and I want to focus on two here: alienation and self-loathing.

I grew up not knowing I was trans, but I knew, nose to toes, that being trans was a bad thing. Maybe the worst possible thing. Before I really even knew who I was, I knew that I had to hide the heart of myself, for my own safety. I grew to hate the parts of myself that people attacked me for, and eventually I started copying the behaviors of people around me—my dad, more than anyone else—in an attempt to obliterate myself, to rewrite myself, to replace myself with someone better. I can even remember, at 13, my conscious decision to do so.

It wasn’t until my dad died from cancer that that armor of self-hatred began to flake and shatter.

My gender dysphoria, as with many trans people, was founded in a rejection of who I am. Not, as transphobes like to imagine, a rejection of my natal biology—it was a rejection of the fundamental self inside me, which used that biology as a weapon of self-harm to keep her subjugated. Every time I rejected that self, I hurt her again and again, stabbing her with the knifepoint idea that she did not deserve to exist, because look at the body and the life I had. Indisputable evidence of the “rightness” of what was and the “wrongness” of her existence. I internalized the hatred of the caste towards trans people and enforced it on myself.

But let’s imagine a kid who didn’t grow up like me, though. They figured out that they’re trans young, and their parents embraced them when they came out. If our basic model of gender dysphoria is that it’s mostly or entirely triggered trauma from cPTSD, how does that fit with this child?

They are told by movies and television that being trans is bad, that them being trans is bad. They hear politicians rant about exterminating all trans people, and watch as law after law is put in place to restrict their most basic freedoms. They’re bullied by their peers just for existing as themselves, and some parents won’t even let them be near their own kids. They are overtly othered, in other words, separated from society, pushed out to its outer edges.

Alienated.

They are powerless to defend themselves, because any attempt to do so is seen as an infringement of the caste’s right to abuse them with impunity. Their attempts to enforce their own identity feel increasingly meaningless, and their isolation grows. Their transness becomes symbolic of that alienation, so any physically identifiable part of them that might possibly give that transness away. The need to exterminate it to be able to pass for a less-oppressed part of the caste becomes an imperative, a weapon they wield against themselves to try to escape the torment of a culture that constantly strikes out against them. “Passing” becomes a holy grail objective to them.

Yeah. Internalized supremacy culture is a real bitch.

Oh, and by the way, when Black trans folks talk about how trans spaces often have a white supremacy problem? This is the root of that problem.

The prison of internalized self-harm

Every single trans person is alienated in our society.

All of us.

And most of us learn profound self-hatred for our transness along the way.

These expressions of emotional self-harm are the means by which we try to squeeze ourselves into higher, safer levels of the caste, and to do that, we have to enact constant self-harm upon ourselves—whether that’s my self-obliterating lack of awareness of my own trans heart or our hypothetical young transitioner who pursues “passing” with a desperate singlemindedness.

And it also explains why it’s so hard to resolve the post-traumatic pain that comes from these expressions of gender dysphoria. After all, the golden rule of healing from complex trauma is that the trauma has to stop before you can heal. If we wait for cisheterosexual society to stop lashing out at trans people before we heal, we’ll be waiting for a very, very long time, won’t we?

Healing trans trauma is a monumental task. We must heal our own relationships with ourselves, setting aside the tools of lifelong emotional self-harm we learned to use before we even had words to describe who and what we are, but we must also and at the same time dismantle our internalized supremacy culture, the belief that it’s better to be one way—any way—than any another.

And yes, that means you have to give up the idea that it would've been better to have been born cisgender if you want to heal.

To draw an analogy, we have to, simultaneously, recover from habitual self-harming behavior, process and work through white supremacy and how our whole belief structure—not just the beliefs connected to us being trans—is based on racist assumptions and power structures that need to be set aside because they’re killing us, let alone the people and the world around us. Many of us have to undergo religious deconstruction. And then, we have to do trauma therapy, one of the hardest and most painful tasks in all of psychology.

And we have to do it in a world that’s constantly trying to punish us for doing any of it.

I won’t claim to be done. In all likelihood, I’ll probably never be finished healing these wounds or unlearning these things. I’ll never be the dream of a person who never had to suffer these hurts, who had to live through these injustices, or who had to learn and unlearn these evils.

I will never be un-broken. You will never be un-broken.

But every step I’ve made has brought me more peace and healing and pride in who I am. It’s why kintsugi is one of my favorite things in the world. It’s why I named this newsletter Stained Glass Woman.

Because we don’t have to be un-broken to become whole again.

Other articles in the Grinding Glass series:

Shattered, a new model for understanding gender dysphoria.

Slivers, a discussion of how we reenact our trauma on ourselves.

Complex Trauma Disorder? I hardly knew her!, which helps you walk through the process of accepting a complex trauma diagnosis.

My parents named me (AMAB) Stacey. I was teased, harassed and bullied for that before I even knew what it meant to be a boy or a girl. Despite the abuse, I could never accept going by my very masculine middle name, somehow, in ways I didn't understand and couldn't explain, that was worse. So I stuck by my 'girls' name and just took the brunt of the bullying.

Now it feels like I finally earned my name, my identity. Not that anyone should have to do that. (and plus side: it made changing my documents way easier! I hated my middle name so much, I only used it when I absolutely had to.)

I definitely felt that transition down in caste from (barely passing) as a "straight white man" or at least a "gay white man" (because real talk I was always very femme in a way that everyone thought meant I was gay, including the kids who routinely beat me up on the playground) to "white trans lesbian". Two of my closest friends, both white, cis queer female academics, who I had been friends with for 10 and 20 years respectively, both started treating me like shit and I had to realize "oh, this is what they look like from below, rather than above in the hierarchy that exists in their heads". It broke my heart to cut ties with them, but it turned out they had always been shitty, and I'd just not seen them from the right perspective to notice it before.