Face First

A comprehensive guide to facial feminization surgery

Foreword: This article talks in non-graphic detail about surgery.

The warm Mediterranean day makes the trees outside rustle just enough to be audible and I wait anxiously in the little office at HC Marbella International Hospital. It’s a lovely little place with an open campus, but I’ve been in meetings, medical checks, and CT scans all morning, bustled off from room to room with such efficiency that I’ve barely had time to appreciate the warmth of the early summer day. This room is a consultation office—my first of the day, after everything else, and the first time I’ve been left alone with my wife, aside from lunch. I squeeze her hand. She squeezes back.

“Do you think it’s going to be enough?” I ask nervously. It’s Friday. My facial feminization surgery is on Monday. This is the first in-person consultation I’ve had, and we’ve flown halfway around the world on a massive leap of faith, paid a little over €24,000 of money from my retirement, plus airfare, in the prayer and the hope that these people can finally fix the facial dysphoria that’s dogged me since I was eleven. That they can make the sobbing, the despair, finally stop.

“I’m sure it will,” B— says with one of her little smiles. She’s always so much more confident than I am about these sorts of things, but I know she’s nervous too. My dysphoria attacks get pretty bad, and none are worse than the ones for my face.

We’re at FacialTeam. If you want a natural-looking facial feminization, they’re supposed to be the very best there is, and there’s nothing I want more in the world.

A door in the rear of the office opens and a gentle-looking fellow with a well-trimmed beard steps in, holding a manila folder. “Hello,” he says, his voice carrying the warm Spanish accent we’re already used to. “I’m Dr. Bellinga. Zoe, right?” We shake his hand, and there’s a little back-and-forth and he covers the boilerplate information he has to recite and that I already know by heart because I’m a lunatic, and I’ve done more reading about forehead reconstruction than any non-surgeon should ever do.

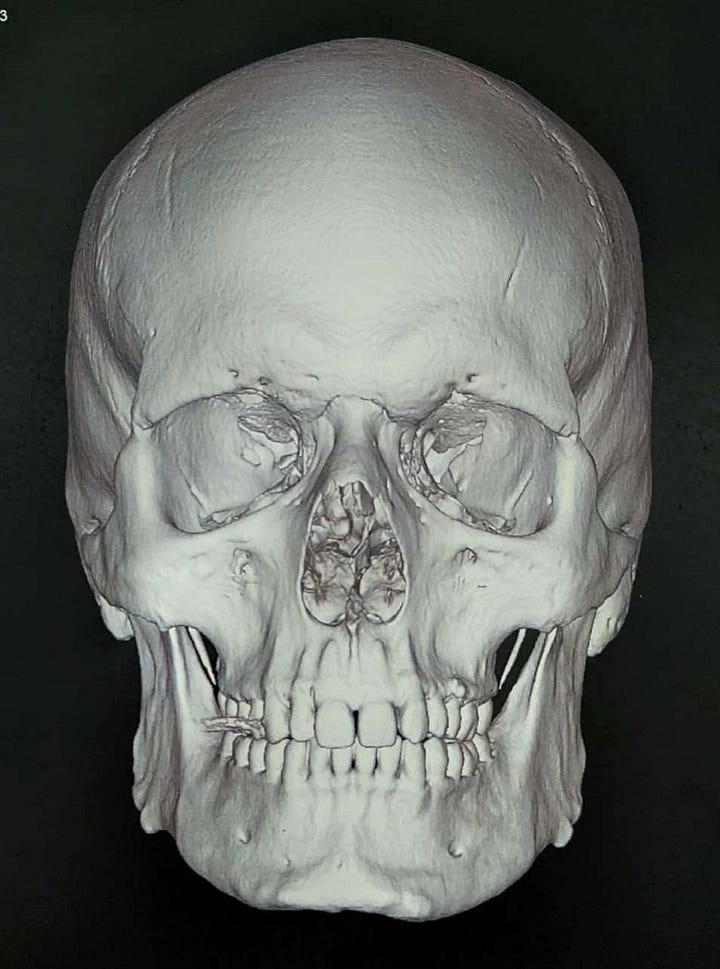

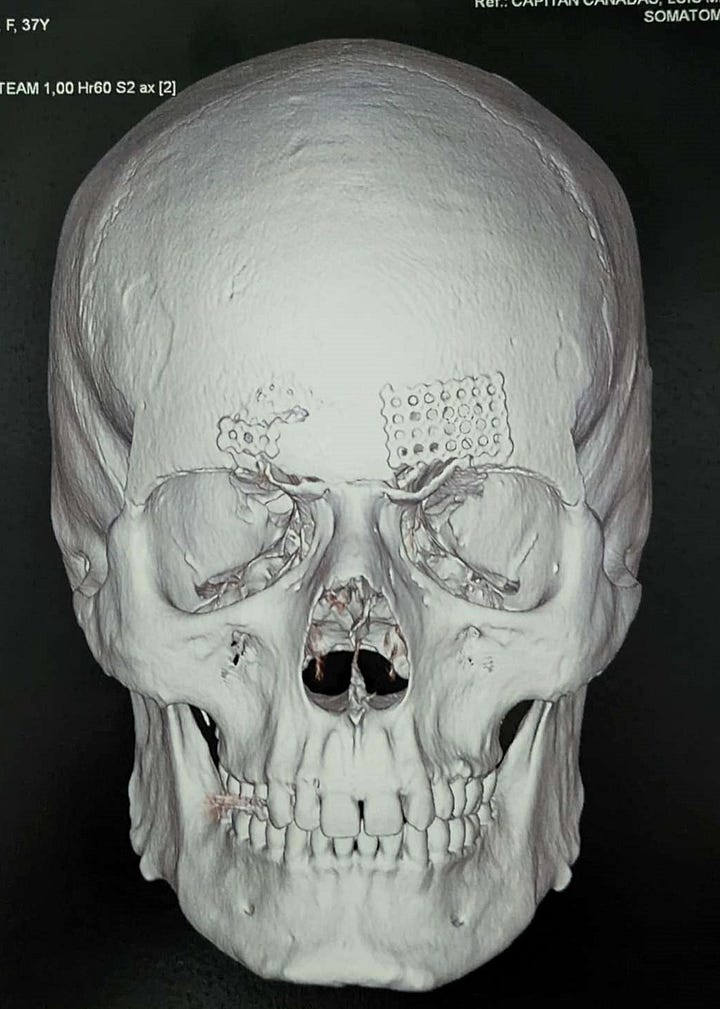

“So,” he says, opening the folder. “This is the scan we took of you this morning. I have to say, the brow ridge is,” he pauses for a moment and shakes his head with a wry little laugh, “much more extreme than we’d thought from the pictures you sent in advance. You have some subcutaneous fat on your forehead that hides a lot of it.”

He’s not wrong. I stare at my skull for a long moment, and all I can see is something that looks an awful lot like a Neanderthal’s forehead ridge.

“Is that good or bad?” B— asks, but my heart is already beating faster, because I know it’s good. More bone means more material they can remove. More they can do.

“Very good,” Dr. Bellinga says. “She is a perfect patient for forehead reconstruction. Let me show you what we can do,” he says, sliding the scan of my head in profile forward and putting a transparent plastic sheet over it. He outlines the current contour in red. “This is what you have now.” A blue pen, now. He draws the contour of my nose, which I love and won’t let them touch, and then just goes straight up—no bump out, nothing. “And here’s what we will do.”

I start crying, choking back tears of swelling hope. Dr. Bellinga smiles, but seems pretty well-used to this sort of reaction. He swaps the profile scan for the portrait scan. “And here’s how we’ll change your orbital sockets,” he says, and the drooping eyes that I’ve always hated are carved away by that little blue pen. I can’t hold the tears back now, and I sit there, blubbering in hope and happiness.

“Is that going to be good?” he asks. I can’t see his expression, but I can hear the satisfaction in his tone. Wordlessly, I nod.

My eyes crack open slowly. I’m still in the operating room with the bright lights of the surgical lamp shining down on me, as they said I would be. A team of three is crowded around my forehead, as they pat one hair follicle after the next into place from the hair transplant that’s the final bit of my FFS. There’s no pain, and it’s best to be awake for this part. Patpatpat on the left as another follicle slips into place.

The skin on my forehead feels odd. A little numb, which is expected, but more importantly, it moves differently. More smoothly. Particularly across my brow. Patpatpat on the right. I try wiggling my eyebrows. They move a bit, and I can feel the smoothness of the way they move. It feels flat. My eyes feel open, for the first time since I can remember.

I start giggling uncontrollably.

“Stop that,” Dra. Moya chides me gently as she works. She’d stepped in to do the hair transplant part of my facial feminization at the last minute, after I had told FacialTeam that I wasn’t comfortable with Dra. Meyer working on me. My consult with her hadn’t gone nearly as well as my consult with Dr. Bellinga had—tears of a different kind there. The emergency patient coordinator, Isabel, had worked through the weekend to make sure that Dra. Meyer would never be in the operating room at the same time I was.

“It’s flat,” I say to her, trying to hold back my giggles. “My forehead is flat.”

“Yes it’s flat, and we have four hundred more grafts to do. Close your eyes and stop giggling so we can work,” Dra. Moya says, her tone a mix of seriousness and warm teasing. I close my eyes and slip in and out of consciousness for a while, warm and happy and finally, finally free.

Hours later, recovering in my hospital room, I get to see my reflection for the first time. I’m incredibly swollen, but I knew to expect that, and I know what it’ll look like when it’s done—and, for the first time since I can remember, I recognize the girl in the mirror.

I still don’t really have words to describe what that was like.

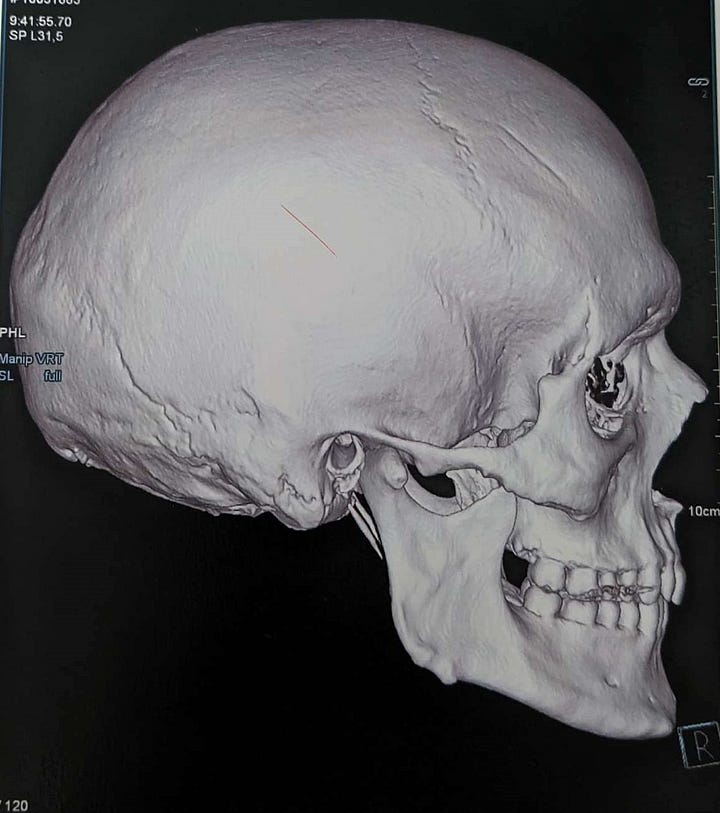

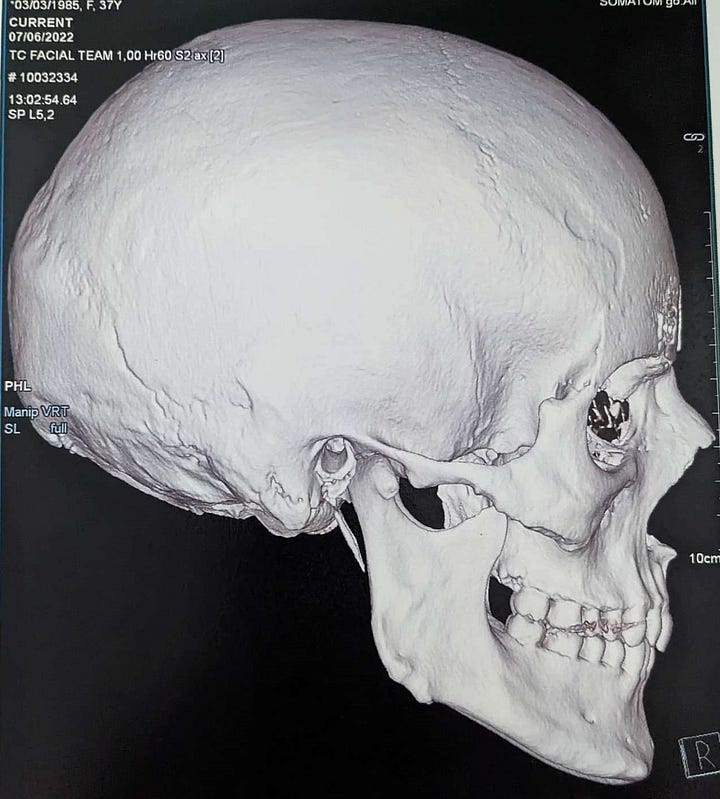

A week afterward, they take new CT scans of my skull. I can barely believe the difference, even though it’s exactly what they promised me.

What the hell is FFS?

If you’ve hung around transfeminine spaces for very long, you’ve probably heard of FFS, but there’s a pretty good chance that you don’t know the full story. FFS is one of the most complicated surgeries out there, easily on part with many bottom surgeries in potential complexity, but it’s also—maybe a little paradoxically—a surgery that can be quite simple.

What the hell, right?

This is because FFS isn’t actually one surgery—it’s a pick-and-choose grab-bag of individual surgeries and procedures that get done together, to feminize a person’s face as a whole. Each person who goes in for it talks with their FFS doctor in detail about what they need, what gives them dysphoria, and what they like about their face as it is, choosing the changes that will make the biggest changes based on their specific facial features. By carefully picking those procedures, the surgeon and the patient work hard to find a combination that’ll change the way the patient’s face will get gendered by other people who see it and, more importantly, resolve the patient’s facial dysphoria.

A note about myself, being gendered correctly, and FFS

Getting gendered correctly is usually called “passing,” which is a term I don’t personally like to use because I’m white, and because of passing’s history as a tool for escaping racialized oppression. The term as it was coined by Black folks has a fundamentally different meaning to how the trans community often uses it—which makes our use feel kind of appropriative to me, but I’ve got a history of being a little over-sensitive to such things, so it may just be me. I’m not going to judge anyone who does use “passing” in this way—I just wanted to explain why I’m using a complicated term instead of a plain one, since I usually try to do the opposite.

Moreover, I’m writing this as a white woman who passes pretty much all the time and chooses to live very out of the closet, as someone who is publicly, proudly trans. That is a massive privilege. Many trans people face life-or-death-level oppression for being trans, where the difference between being gendered correctly in the wrong place at the wrong time can result in them being straight-up murdered. The intersectional oppression that BIPoC trans women have to face magnifies the ways that womanhood is policed on members of those communities—particularly the Black community—and significantly increases the rates at which they are made into the victims of violent acts. As such, FFS is often a lifesaving surgery that is urgently, desperately important, regardless of the more personal feelings or dysphorias of the person getting it.

But some of us aren’t in that kind of situation. We just want to live our lives, be respected for who we are, and recognize the person in the mirror when we look at ourselves. Despite that, I’ve heard from so many transfems in safe situations that they want FFS to be gendered correctly. That fighting dysphoria is a distant second place to them in importance.

That’s not a good place to be, and it’s not a good place to make decisions about major surgeries from. Ultimately, it’s valuing other people’s judgment about how you look higher than your own, which is a form of internalized transphobia. It’s the same thing as staying closeted because you’re afraid of how your family will react.

If you aren’t going for FFS for your immediate, physical safety: please take the time to work on these feelings in therapy before finalizing your plans for FFS. Get this procedure, but get it for you, and nobody else in the entire world.

Why we do a thing matters. You deserve to love your reflection more than anyone else in the world.

So… what are these different techniques?

Because FFS is a big bucket of possible surgeries aimed at changing the apparent gender of a face and resolving a patient’s dysphoria, each person needs to pick and choose the surgeries that are right for them. For instance, I needed forehead reconstruction, orbital contouring, and a hair transplant, but I’ve always loved my nose, and didn’t feel that my jawline was masculine—all of which FacialTeam agreed with me on.

I’m going to lay out the different procedures you can get, what’s involved in each, how tough the physical recovery is, and I’ll add a note for how significantly the research says that procedure can feminize a face where the base structure is causing a person to be gendered incorrectly. That last bit is important—if you “feminize” a structure that’s already within normal feminine ranges, the result can look… weird. Be thoughtful—this isn’t the sort of thing where you can just tell a doctor “go as feminine as possible” and call it good. A face is a gestalt, which means that the whole is a lot more than the sum of the parts.

So, remember: go for a balance, and when in doubt, work to resolve your dysphoria more than working to be gendered correctly. Preserve what’s already good, and change what’s not working. Nobody’s going to need or want all of these procedures.

Forehead Reconstruction—Major Change

Forehead reconstruction comes in 3 types, and the main difference between them is how much bone needs to be removed and what kinds of repair or replacement needs to be done afterward, based on the bone removed. For instance, I had a Type 3 forehead reconstruction, because a sinus cavity was exposed during the procedure—that’s what those bits of titanium mesh are for in my “after” CT scans. They protect the cavity and encourage bone regrowth.

For all types of forehead reconstruction, the surgeon will make an incision from ear to ear, either along the patient’s hairline or inside your hair (this is called a coronal approach, and is less common). The skin and fat are peeled down to the patient’s eyes and, basically, a surgical-grade Dremel tool is used to sand down the brow bone. Sometimes, a piece of bone needs to be cut out and repositioned. Then, finally, the skin and fat are replaced, and the incision is closed with a whole bunch of stitches. Forehead reconstruction is generally considered to be the definitive technique of FFS; it’s pretty rare to have FFS and not have a forehead reconstruction.

Increasingly, forehead reconstruction and orbital shaves are done together, because it’s very rare to need one and not the other.

Recovery: Pretty easy, in terms of pain. I’ve had worse flu recoveries. However, it’s very slow; once the initial swelling heals, the fat and skin of your face, which has adapted to your brow ridge being there, will sag and look pretty terrible for a while. Expect it to take about a year for everything to adjust fully.

If your doctor goes in with a hairline incision, it’s incredibly important that you stay out of the sun for the first 6-12 months of your recovery. If you tan a lot, it can really highlight your incision scar, making it highly visible for a long time. This is the reason some doctors use a coronal incision—your hair hides and protects everything.

Orbital Shave—Major Change

An orbital shave is done by opening up a patient’s face in the exact same way as forehead reconstruction, and often as a part of that surgery. A rotary tool (that same surgical-grade Dremel) is used to sand down the shape of a patient’s eyesockets, to remove the shape changes that testosterone in puberty generally causes in them.

Orbital shaving is a newer FFS technique, but most experts say it makes just as big a difference for facial feminization as forehead reconstruction.

Recovery: The same as forehead reconstruction, except that your eyes tend to swell pretty badly in day 3-4 of your surgical recovery. Think “two nasty black eyes,” plus the same long, slow readjustment you see with a forehead reconstruction.

Hair Transplant—Moderate to Major Change

A hair transplant is usually performed by removing a strip of hair from the back of a patient’s head, using a microscope to dissect each individual follicle, and then transplanting each follicle by hand to reshape the hairline. A less-common version of the technique uses a robot to move each follicle individually, but it’s not used very often for facial feminization because it’s slower than using a strip.

How much a hair transplant can feminize a face depends a lot on how receded a person’s hairline is. For people who had very badly receded hair like I had, it can make a dramatic difference in how a face is gendered. For others, with a simple M-shaped hairline, it can actually have no effect whatsoever—many cis women have M-shaped hairlines. As a result, hair transplants are often more about resolving dysphoria than changing the way a face is gendered—but that doesn’t make them any less important.

Recovery: Low pain, but rough and slow. You’ll have to sleep on your back and sitting up for about a month, spray your forehead with saline every half hour for about a week after the operation, and avoid getting sun on the transplant area for about three months, so find a hat you like. All of the transplanted hair will fall out after about a month, and it won’t start growing back until month 3-4. You won’t see full results for 12-18 months.

Hairline Advancement—Moderate to Negative Change

To perform a hairline advancement, a surgeon makes an incision along your hairline, removes a strip of skin an inch or two wide in front of it, and pulls your hairline forward, reattaching it with the removed strip of skin thrown away. For someone with a badly receded but otherwise-full hairline who’s already having FFS—and especially when they’re getting a standard hairline incision for that FFS—a hairline advancement can dramatically reduce (or even completely replace!) how much of a hair transplant you need to have a feminine hairline.

But!

But feminine hairlines don’t vary as much as masculine hairlines do, and if you pull a hairline forward too far—and, remember, with FFS, there’s a lot of soft tissue readaptation, which isn’t always perfectly predictable—it can actually masculinize a face. For this reason, an increasing number of FFS surgeons won’t do hairline advancements except in very special situations, and even then, they’ll usually lowball how much they advance the patient’s hairline on purpose, meaning they’ll still need a transplant later. Overshooting on a hairline advancement is bad.

Recovery: Similar to a forehead reconstruction, because it’s basically the same move-the-skin-and-fat maneuver that a forehead reconstruction is, with the extra bit that you have to seep sitting up for about a month while things heal.

Eyelid Surgery—Very Mild to No Change

This one’s called a blepharoplasty in medical terms, and I’m mentioning that because few people will call it “eyelid surgery.” Basically, fat under the skin of the eye is moved and removed, and a small incision is made to tighten the skin of the eyelids themselves.

Bellaphroplasty is usually considered to be a purely aesthetic technique, though it can have a small feminizing effect for people with very droopy eyes when their skin doesn’t quite heal ideally from a forehead reconstruction. If you’re getting it as part of a forehead reconstruction, though, this one’s definitely aesthetic.

Recovery: Not too bad, but expect very swollen eyes for a few days after surgery. Have lots of ice packs!

Nose Job—No Change

A lot of people get a nose job as part of their FFS, and I expect that me saying it won’t change how you’re gendered going to be a little controversial. Thing is, the research says, pretty convincingly, that changing a nose doesn’t affect the way a face is gendered. Because of this, a nose job is almost always considered to be a beautifying technique by itself.

Thing is, a nose job is also how you fix a deviated septum, which is really, really common—as many as one in three people have a deviated septum, and when you have one, a nose job is medically necessary. Better yet, FFS surgeons are the exact specialty of doctor to do a nose job, so it’s pretty common for people to get a nose job as part of FFS.

A nose job is pretty simple. A surgeon makes a couple of incisions in the nostrils or, sometimes, through the outside of the nose. They’ll use tools to cut, remove, and reshape the bone and cartilage of the nose, then set it in place with a splint after closing the incisions.

Recovery: Painful and stressful. Post-op swelling often forces people to breath through their mouths for weeks, which can be really irritating for many folks. Expect headaches, especially if you had a deviated septum corrected. Your nose will start to settle into shape about four months after surgery, with final results after 9-12 months.

Cheek Implants—No to Minor Change

Cheek implants are small silicone domes that a surgeon can insert on top of your cheekbones to give you rounder cheeks. This is almost always a purely aesthetic surgery. To do it, a surgeon will make small incisions on either side of the inside of your mouth, and use those to slide your cheek implants into place, then close the incision.

You can get pretty similar results with filler, like Juvaderm, which lasts about 9 months and will cost much less. Filler can be a great, affordable way to try out the look you could get with cheek implants.

Recovery: Swelling for about a month, but otherwise fairly easy. Don’t eat or drink acidic things until the incisions in your mouth have healed, or you’re in for a pretty sharp jolt of pain!

Fat Removal—No Change

Using a small version of the suction tool that doctors use for the kinds of liposuction you’ve probably heard of, a surgeon can remove fat from your cheeks, neck, and face. This works just the same way as any other liposuction, just on a small scale—the surgeon makes a small incision, and uses it to suck out the fat you want gone. Unsurprisingly, this procedure is entirely aesthetic, and has no real effect on feminization by itself.

Recovery: This can be pretty painful, relative to the small sizes of what the surgeon removes, right after surgery, and you should expect some bruising. Recovery is relatively quick, but it can take a while for your skin to adjust.

Lip Lift and/or Filling—Minor Change

Full lips are generally considered more feminine but—and this is important—thin lips aren’t unfeminine; as a result, lip filling and/or lifts have a fairly minor effect on feminization. For a lip lift or when a silicone implant is inserted, a small incision is made inside your mouth, and the surgeon will either insert a small silicone implant or adjust the connection of the muscles and fat of your lip to your skin.

You can also use Juvaderm to get most of the same effect. It lasts for about nine months per injection process, but it’s a lot cheaper, so it’s a great way to try before you buy, so to speak.

Recovery: About the same as for cheek implants for a lift or lip implants. For filler injections, you’ll be good to go in about a week, with only minor pain on injection day.

Jaw Contouring—Moderate to Major Change

A surgeon will make a few incisions in your mouth, detatch your jaw muscles from your jaw, cut a long slice out of the underside of your jaw through those incisions, and then reattach your jaw muscles.

And if you’re thinking that that sounds very painful and like it’ll make it hard to chew for a while, you’re exactly right.

For people who got heavily angular, thick jawlines from testosterone puberty, jaw contouring can absolutely transform to how their face gets gendered. It’s also definitely the most invasive possible part of FFS, and the part with the hardest recovery.

The biggest thing you need to be ready for with this surgery is that your chin and neck will sag badly for months after surgery, even when you wear the chin strap that your doctor will give you as much as you possibly can. This is very frequently a source of huge dysphoria during recovery, because your jaw and neck will look worse than they’ve ever looked before in your life.

Be ready. Especially around month 4 of your recovery, make a point of reminding yourself that soft tissue readjustment takes about a year.

Recovery: Painful, hard, and dysphoric. After surgery, you’re going to be ravenous, because your metabolism can as much as triple after major surgery. At the same time, you’re not going to be able to eat things that aren’t soft for the first couple of weeks after jaw contouring (and, in tough cases, for as much as a month or so). Even for the things you are able to eat, it’s going to be slow going; one of the girls who got her jaw shaved at the same time I was recovering in Marbella budgeted an hour and a half to two hours of time per meal while I was there. On the upside, she got to have all-she-could-eat gelato, so it’s not all downside in that respect.

You won’t see final results for a year or so after surgery.

Chin Contouring—Mild to Moderate Change

Chin contouring works in mostly the same way that jaw contouring works—a surgeon makes an incision in the inside of your mouth, slices off the tip of your chin, and then either moves it forward to strengthen your chin or backward to reduce it, depending on what you need. Some surgeons, as a note, prefer to come in from the underside of your chin, in which case you’ll want to take good care of the incision so the scar won’t be visible. In either case, chin contouring is usually done as part of jaw contouring, but sometimes do it on its own.

Because it’s a smaller surgery, it has a less dramatic effect on your face’s feminization than a full jaw shave does, but your chin is the most noticeable part of your jawline. That means that chin contouring can have a really disproportionate effect on how you’re gendered, relative to how big it is.

Recovery: Similar to chin contouring, but a little less intense in every way, and for all the same reasons. Since most people who have chin contouring get it as part of jaw contouring, there aren’t very many reports that I could find about how hard the recovery for just this procedure is.

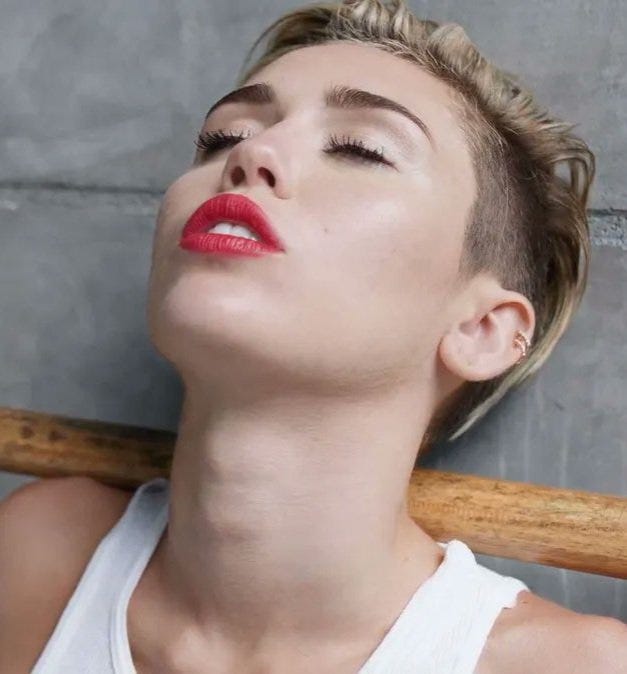

Tracheal Shave—Moderate Change

The surgeon makes a small incision underneath your chin. Then, they use some very small tools to shave down the thickened cartilage of a trans person’s trachea—the spot that people usually call an Adam’s Apple. For people with very sharply pronounced tracheas, this can make a really dramatic difference in their profile, but it’s also important to remember that it’s really common for cis women to have pretty noticeable tracheas too—and not just random women. Famous women. Gorgeous women.

For instance, Miley Cyrus.

I mention this because sometimes people go in for a trachea shave and are disappointed with the results because they expected a completely flat trachea and didn’t get one, or ask for a tracheal shave and are refused by their surgeon. There’s a really important difference between a pronounced Adam’s Apple and a visible trachea—and the latter is very, very typical for women of all kinds.

Recovery: You’ll have a pretty sore throat for a couple of weeks post-op, and a lot of people find that it’s worthwhile to stay pretty quiet for that time. That said, the recovery only takes about a month, and you’ll usually see your results really quickly.

One Year, One Recovery

It’s one thing to read “this recovery goes like such-and-so,” but it’s really different to live through it, and the hardest part of FFS is that it’s a huge, life-changing surgery that you don’t really get to see the results from for a whole year.

That. Sucks.

So, here’s what recovery looked and felt like for me, as someone who got forehead reconstruction, orbital shaving, and a couple of hair transplants.

With pictures.

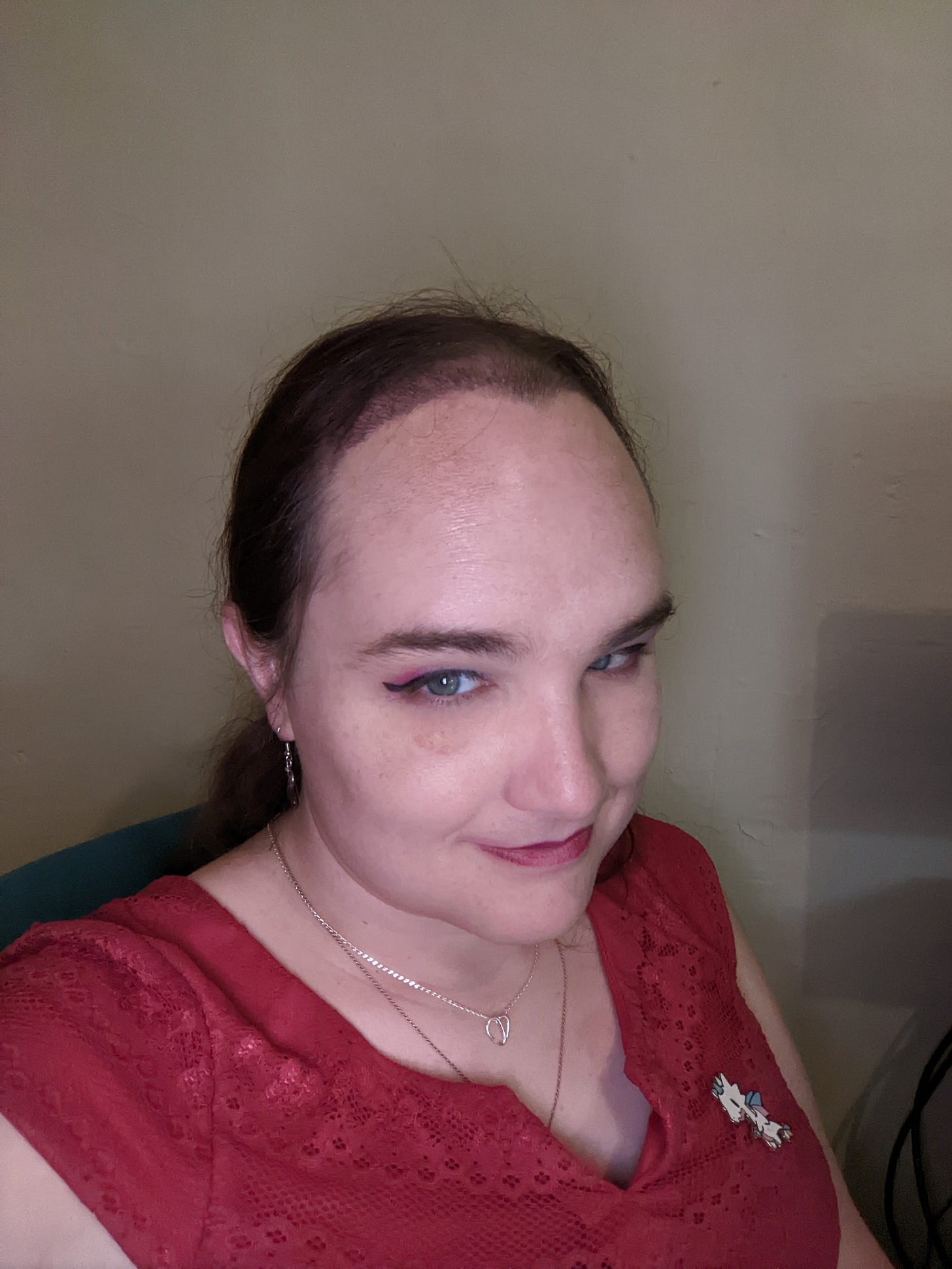

Here’s where I started, the night before surgery. No makeup, no clever tricks.

The Immediate Aftermath

I spent the night after my surgery in the hospital, but I bounced back pretty quickly, and was discharged the second day. Two days in the hospital is more common, though, so be ready for that. In the afternoon of the second day, I got into a taxi, hair covered lightly by a shawl, and went back to my hotel room. This is how I looked, give or take.

For the next two days, I was tired, and stayed in my hotel room, resting and ordering take-away food, while my incision got cleaned every morning by a nurse from FacialTeam. On day 3 after surgery, my eyes swelled so badly that I had to cycle through four cold packs to keep them from swelling completely shut. The saline I had to spray on my hair transplants to keep them healthy dried and crystalized in the rest of my hair, leaving it a salt-covered mess. After that, I was still pretty puffed up in general, and that didn’t really go away for about a month. After two weeks, this is how I looked:

For the first couple of weeks of my recovery, I would get tired pretty easily, and the top of my scalp was completely numb—which meant that it couldn’t sense temperature, and in turn couldn’t sweat. I had a couple of moments in the hot, hot Spanish summer where I got really dizzy because I was overheating. If I hadn’t had cold packs and strong air conditioning, things could’ve gotten pretty bad—heatstroke bad.

Respect the heat and your inability to sweat during this time. You’re at higher risk for stuff like heatstroke and heat exhaustion until your nerves start healing.

Early Recovery—Months 1-4

After I got home, the hair that had been transplanted all fell out and my swelling finally went down. Early recovery from FFS has a very, very well-deserved reputation for being a dysphoria trap, and I fell into it. Even though I knew what was going on was normal, even though I knew I needed to wait for my face to heal, I fell hard into despair, in large part because I had bad shock loss in my hair, and the rest because the reduced swelling made my brow look worse than it ever had before. This was me at month 3 post-op:

Shock loss is a very, very common side effect of scalp surgery of any kind, and when it happens, hair follicles freak out and shed their hair, then go dormant for a few months before they start growing again. The result? My hairline looked worse than it had any time since I started estrogen. Combined with a very saggy brow that had yet to begin its readjustment, I felt that I looked more masculine than I ever had, and with pretty good justification.

I spent most of Month 4 in a pit of total despair.

Expect this period to be the hardest part of your recovery.

Things Start Improving—Months 5-9

Around six months after a hair transplant, the transplants are starting to grow in earnest. You’re still only seeing around 40% of them doing anything at all, and what hair they are making is thin and scraggly, but it’s enough that things start to move in ways you can actually see. At the same time, this is when soft tissue readjustment really starts to have visible effects, with my saggy browline starting to pull up and snug into place. This happened unevenly for me, with the saggiest part—the bits on the insides of my eyes, near my nose, continuing to sag very noticeably. Here’s where I was at about Month five and a half:

During this time, I got a second hair transplant. We had known I’d need to from the moment I went in for my FFS, because I’ve got Type 2A hair, which is unusually thin, and just because of the number of follicles FacialTeam had been able to harvest just wasn’t enough to fill in the area I needed. Dra. Moya had actually told me as much as she was working on me in the operating room.

As such, I’m not sharing shots from later on in this period, because that second operation kind of makes for some complicated and not-entirely-representative shots. But, that’s why you’ll see my hairline shift again at…

Olly Olly Oxenfree—Month 12-18

The one-year mark is when you can expect to see the full results of your FFS. There’s often some straggling tissue readjustment if you had a particularly dramatic reconstruction—say, you went from an extremely square and thick jaw to a much more petite one—that can drag on to 18 months post-op, but the heart and soul of what you’re going to look like should be obvious on the anniversary of your surgery. This was what I looked like then:

And by 18 months, which is where I am now, you’ll really be seeing everything there is to see.

So… Where Should I go if I Want FFS?

You can see how I look now, and how I used to look. I’m gonna put in a solid recommendation for FacialTeam, because I’m really happy with my results—but they might not be right for you. The most important thing to do is careful research, and the best place to start with that is with the /r/Transgender_Surgeries subreddit wiki. They’ve got surgeon-by-surgeon reviews, with pictures, so you can see what the work these folks have done looks like. Realself is your second-best choice for this research.

In general, FFS surgeons have two philosophical approaches. The first is to work to eliminate what testosterone did to your body, preserving as much of your original look as possible, just without things like a brow ridge or a heavy jaw. The second is to take the opportunity of FFS to beautify your face as much as possible.

The Best of the Best

If you’ve got money to burn or great insurance and want the best of the best, you’re going to see a few names come up over and over again. Generally speaking, these folks are the best out there:

FacialTeam is generally considered the best in the world at creating a natural look, and their postsurgical care is second to none. These two things are why I chose them. They’re based in Marbella, Spain.

The Spiegel Center is an outstanding FFS center, and Dr. Spiegel is one of the best out there for magazine-beautiful faces. He’s based in Boston.

The Deschamps-Braly Clinic also specializes in making magazine-beautiful faces, but Dr. Deschamps-Braly positions himself as an expert on non-white physical aesthetics, which may be of particular interest to some folks. He’s based in San Francisco.

Dr. Keojampa is, arguably, the rockstar of the FFS world, and patients have posted remarkable results with both natural looks and more magazine-beautiful faces. With his rockstar reputation, however, comes rockstar wait lists and rockstar prices. He’s based in Los Angeles.

But just because you can’t go for the best doesn’t mean you can’t get incredible results; do your research and you can find some amazing surgeons that haven’t gotten the attention that the big names have. For example, there’s a FFS doctor working in Detroit, near me, named Dr. Garcia-Rodriguez, who spent years as one of Dr. Spiegel’s assistant surgeons. Several of my friends have had their faces done by her, and I’ve been very impressed by their results. There are a lot of doctors just like her all around—former fellows of the best of the best, who know all their tricks and techniques, and who’ve gotten out on their own.

You don’t need to be rich or to do reckless things to your retirement, like I did, to have an amazing face. Promise.

One last thing, since I’m sure you’re wondering:

Yes. Yes, it was worth it. It was worth every cent. I still find myself giggling with joy at how I look in the mirror.

Bonus! Wedding pictures!

I wanted to thank you all for your patience while I ran off and renewed my vow. So, allow me to share a couple of pictures of myself and my beloved B—, courtesy of the incredible Liv Lyszyk.

I'm scheduled (fingers crossed!) for facial surgery near my home in Seattle early next year, which happens to be the 37th anniversary of when my partner and I started dating, way back in high school. We're renewing our vows next year on our 33rd wedding anniversary, six months after facial surgery. I'll look however I look, and I'm fine with that.

For me, there's not really a difference between wanting to be gendered correctly and relieving my dysphoria, because the person who misgenders me the most based on appearance is *me*. I want to see the girl in the mirror, not just sometimes, peeking out from under a heavy brow ridge, but clearly and all the time. I want other people to see her too.

I don't have any control over how a given person perceives my gender, and I don't particularly care. The individual misgenderings don't bother me, whether they're an accidental slip from someone who knows better, a person getting conflicting signals and guessing wrong, or even intentional, hateful slurs. Fortunately, I've experienced very few of the third kind. But the weight of all of them together is a constant background irritation that I don't need. If FFS can reduce that irritation, that's a valuable improvement in my life. Not as important as what I see in the mirror, but still important.

My main concern, like you, is my brow ridge. I rarely bother with eye shadow because you literally can't see it when my eyes are open. I'll be having a forehead reconstruction and orbital shave, which will include a (minor) hairline advancement. I'm also getting a trach shave and lip lift. I'm not having a hair transplant as part of my surgery, but I might have a separate procedure later.

Thank you so much for the detailed explanation. I already know this stuff because I've done plenty of my own research and had consults with three surgeons, with a fourth this month as a backup, but this post is a great resource that gathers a whole lot of information in one place. Thank you also for sharing your personal experience with recover, and especially the photos.

And congratulations to you and B---- on your vow renewal. You both look gorgeous!

Thank you for sharing the details of what FFS can consist of and your journey. A friends wife recently had FFS and I was curious but I felt it was inappropriate to ask questions. I am so happy you get joy out of how you look now. :)