A Rose by Any Other Name

How language restricts scientific thinking, and how we're working to change it

There’s a lot about the nonbinary experience that I don’t understand.

I don’t say this as any sort of slight, except maybe against myself, for the failure of my own imagination, but at the end of the day, I’m a pretty basic binary trans woman. While my story is a far cry from the one that Harry Benjamin minted back in the ‘50’s and which psychologists around the world calcified in the ‘60’s—I didn’t know until, one day, I knew—my transition would look pretty familiar to Benjamin and his team. I went to a psychologist, started HRT, and came out publicly. I got a few surgeries, some a little more… prominent… than others. Skirts and dresses are my everyday. I like women, which would’ve rubbed them the wrong way, but except for that and maybe one or two other details, neither I nor my transition would merit so much as a footnote in anything they wanted to write about transness.

I am, give or take, fairly standard issue.

Stop. Think about that for a moment.

Why does standard issue for the entire incredible diversity of the trans experience mean “white, middle-class-or-better, classically feminine, binary trans woman?” Where are the trans men? Where are nonbinary people? And when you think of trans men or nonbinary people, what are the images that spring to your mind?

Think about it for just a moment before you keep going.

When you thought of a trans man, did you imagine a short, soft-looking guy, maybe with a bow tie? Perhaps with a short, scruffy beard that’s not quite there yet? Hints of some mythic natal femininity still clinging to him, how gender assigned at birth still, just barely, discernable.

And that nonbinary person—which shade of bright neon color was their hair, in your imagination? Did you imagine a binder, just peeking out from a button-down shirt, visible enough for you to know it was there? Again, they’re definitely white, aren’t they? And definitely slender.

Now, here’s where it gets really fun: unless you, the reader, were either a trans man or nonbinary, in which case I’d bet you thought of yourself, I’ll bet that there was more than a little bit in those descriptions that hit the mark of your imagination. And why? Well, scan through them again.

How many tiny indications of those people being rebellious females assigned at birth did I leave scattered through there, odd details to match with our implicit biases, which is our set of attitudes and stereotypes that we build up over a lifetime and which we don’t recognize as anything other than fundamentally true? And I say our here, because as much as I fight to deconstruct my own internalized implicit biases, I definitely carry them myself. You do too, I guarantee. Everyone picks them up.

When we trace the medical, social, cultural, and rhetorical way that we build up what it means to be transgender in any way, for most of the last century, being trans has been a condition that is fundamentally about femininity—either the embrace of it by binary trans women or the inching rejection of it by nonbinary people—who are far too often framed as “woman lite”—or, occasionally, the wholesale disconnection from it by binary trans men.

Where are nonbinary transfeminine people? And why do the enbies you imagined look androgynous? A lot, maybe most, don’t.

What about feminine trans men, delighting in the same skirts and dresses that I do? Or wildly successful, world-class athletes?

How about masculine trans women, fighting for gains in the gym with the bros?

I’m far from the first person to poke at this reality—it was one of the central pillars of Whipping Girl, in 2008, for instance, and has been a touchstone of Serano’s work ever since. A lot of people have written a lot about how this is philosophically problematic—gosh, that’s a word I hate, as if anything could manage to not have some sort of problem in it somewhere, ever—and how we should be more inclusive of people across the gender spectrum. They’re right. And yet, this stereotype, this myth, persists, even among trans people ourselves.

Don’t believe me? Think we’re better than that? Okay. Check this out, then:

That graph is from the 2022 United States Transgender Survey, the largest survey by almost an order of magnitude ever conducted on trans people, with over 93,000 participants.

Why are there about 30% more trans women than trans men? Why are there almost four times as many transmasculine enbies as there are transfeminine enbies? There’s no reason we’ve ever found that would make any part of transness be more of a thing for folks with XX chromosomes than XY or vice versa, and especially not one that’d explain such a massive difference in the proportion of nonbinary people. But there’s a more important question at stake here, and it’s one the scientific community has only very recently begun to ask:

Why is basically none of our research into transness done into nonbinary people?

Because that’s a question that affects a massive number of people, who have been almost entirely forgotten by, well… pretty much everyone.

Including the wider trans community.

Conceptual metaphors

What do women, fire, and dangerous things have in common? Yeah, I know that this feels like a swerve. Hang in there with me, though—it’s important, and it’s the answer to the other question.

If you’re George Lakoff, one of the most important linguists who ever lived, those three things are the title of the most important book you ever wrote. The core idea of the book’s title is that those three—women, fire, and dangerous things—share, to a cis, white man like George Lakoff as well as many other cis white men, a categorical feature: they are all inherently dangerous to men. These have a symbolic association, which is a fancy way of saying that the things themselves have a larger meaning to us, and that that larger meaning forms categories. In simpler terms, though, these things are all metaphors, like you learned about when you studied poetry in school. To borrow a smidgen from Shakespeare, “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet” isn’t about roses, it’s about Juliet, and how Romeo doesn’t really care that she’s a member of the Capulet family that wants him dead.

When you learned about poetry, you learned about how people can use metaphors to say one thing and really mean something else, using the symbolic relationship between those two things. The thing is, Lakoff and other cognitive linguists have learned that it’s very much a two-way street: sure, we make our meaning known through symbol, simile, and metaphor, but our how we conceive of the world around us, to understand its fundamental workings, is governed by metaphor.

Not just our thinking, but our very ability to think and learn is limited by these metaphors.

Now, that might sound pretty spooky to you, but it’s really an everyday thing. I want you to think back to the last time you had to learn something you didn’t know. Was the process a sort of slowly-filling loading bar? Where you learned and learned with each bit slowly building your knowledge until Understanding Was Achieved?

Or was it a little more like this:

You had that moment of epiphany, where you said to yourself something very much like, “oh, it’s just like X, except Y!” And suddenly, everything made sense, after that moment of crystalline realization.

Gosh, it’s not like there’s anything like that that’s become a cornerstone of the trans community.

Gosh, nothing like that at all.

Conceptual metaphors are how we learn, and why we don’t understand something at all until we get it completely. They’re also why it takes babies a year or sometimes two to say their first words, months after that to pick up a few dozen more, and then a sudden avalanche of vocabulary comes at a rate that’s almost impossible to believe. By using these conceptual metaphors, we use existing knowledge to bootstrap new knowledge, using the things we already know to build knowledge rather than craft entire new scopes of understanding from scratch. It’s why knowledge and understanding about things seems to grow exponentially, and quickly, once it passes a certain point, both individually and in the public consciousness.

It’s incredibly efficient. Complex thought, let alone personalities and society as a whole, wouldn’t be possible without learning through conceptual metaphor. But it also limits our ability to imagine, let alone research or understand, things outside of that existing frame of knowledge.

And if (overwhelmingly-cis) researchers think of transness as being about femininity on a fundamental level—wrongly, to be clear—they’re going to build all of their research tools around that bad idea.

Which is why basically no research is done about being nonbinary, and why the significant majority of all research is about trans women. When researchers think “trans,” they unconsciously fill in the blank with someone who looks a lot like me, in the same way most of us filled in the blanks earlier in this article with incorrect, stereotypical versions of trans men and nonbinary people.

Implicity

There’s a lot about the nonbinary experience that I don’t understand. Most of it, really, and that’s because I’m binary—in the same way that, I suspect, many nonbinary folks don’t really understand what it means to be binary. My understanding of transness as a whole was something I built based on my own experiences, my own knowledge, my own perspectives, and no matter how much I learn and grow, I’ll never be able to get away from that central fact.

And that’s okay. It’s normal. Unavoidable.

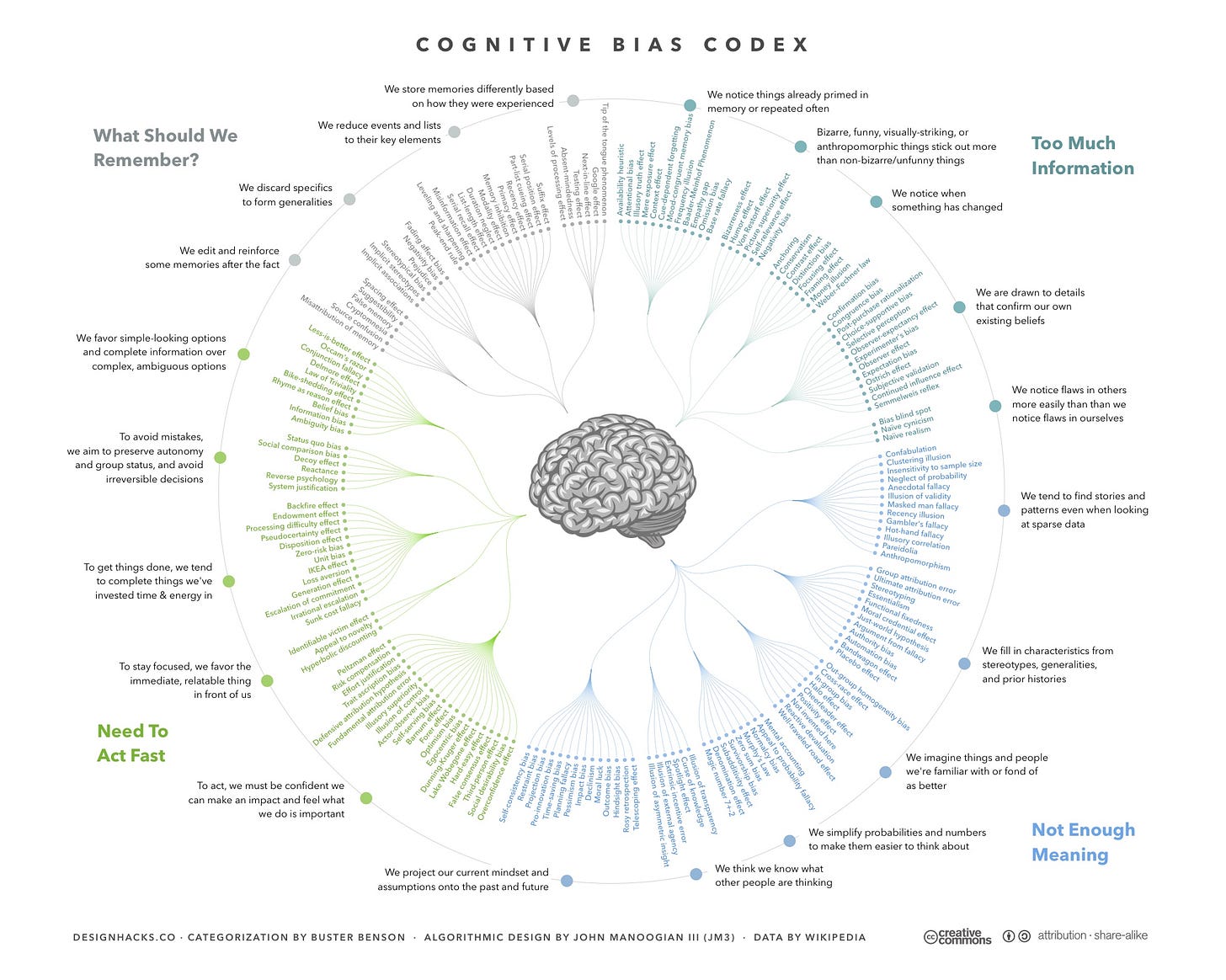

This is an implicit bias I carry that comes from the cognitive metaphor I used to come to terms with my own transness—in my case, an affinity bias. And there are a lot of biases that we all carry around with us, like forgotten homework at the bottom of a schoolbag we’ve had for too many grades. How much? Well…

… a lot. A lot a lot.

That’s the sacrifice we make as a species that learns through conceptual metaphor. We trade away the ability to get total accuracy so we can instead have speed, conceptual synthesis, and good-enough understandings that let us do an incredible amount.

To be clear: trading perfect accuracy for these things is a really good deal. Perfection is never really achievable anyway. But that means that cognitive biases are something every scientific researcher has, and that they apply to every single field of study out there. Like wolf biology.

Yes, wolf biology.

You see, for decades, researchers and the general public believed that wolf packs lived in a strict hierarchy, with a large male keeping vicious control over the group. Certain sorts of men have even taken on the terms for these hierarchies to describe their own sexist ideas of fiat rulership over their friends and, unsurprisingly, the women in their lives.

And all of it came from the sexist biases of mid-20th-century wolf behavior researchers looking at wolves in zoos. There’s no such thing as an alpha wolf—just a mom, a dad, and some kids.

One of the most important parts of being a good scientist is recognizing your implicit cognitive biases and designing research that doesn’t project them on whatever it is that you’re researching. And we’ve gotten a lot better at it over the years, as researchers have taken feminist perspectives more seriously and redone research people had thought was long-settled.

New modes of research

I’ve talked a lot about Julia Serano’s work on Stained Glass Woman, and I obviously think a lot of her, but one area where her work falls short is right here—the importance of conceptual metaphor on human cognition, despite the fact that her work is built on that very principle—that researchers in psychology, anthropology, biology, feminism, and a bunch of other fields of research brought their own biases about what it means to be trans to the table, and that when they did so, they mucked everything up.

In the foreword to the last two editions of Whipping Girl, Serano talks about what she calls the revolving door of trans terminology, and resists the call to newer terms. Her resistance is… unfortunate, because doing so reinforces her—and our—own cognitive biases.

This is a problem, fortunately, that the wider research community is paying close attention to. A recent article in Nature argues, with excellent evidence, that researchers’ biases to see transness through the lens of femininity and especially through the lens of a binary gender system that’s just plain wrong has led to a lot of inaccurate and incomplete research. In essence, they argue that the way you ask a research question shapes the answer that the research will find, so the starting perspective of all these studies has screwed up their results—and that’s both on the researcher’s side and on the side of participants:

In the United States, an estimated 9.2% of secondary-school students don’t wholly identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, yet only 1.8% anonymously answer ‘yes’ when asked whether they are transgender. These identities are not trivial. How people identify shapes not only their experiences of marginalization, but also their bodies — be it by influencing their smoking habits, whether they exercise, what they eat or whether they undergo hormone therapy or transition-related surgeries.

Human experiences are inevitably richer than the categories we carve out for them. But finding the right concepts and language to describe their diversity is an essential part of the scientific endeavour. It helps researchers to capture the experiences of participants more accurately, enhances analytical clarity and contributes to people feeling included and respected.

They propose “gender modality” as a term that would allow researchers to think of how a person’s gender relates to their gender assigned at birth. The term has a lot of uses, but they’re drawing it from the meaning in statistics, where several groups can have overlapping, intermingled tail ends.

And it’s a really good shift, because it encourages researchers specifically to think of gender as not being binary. That means more, and more meaningful, research on nonbinary people, on detransitioners and retransitioners, on questioning folks and, as they note specifically, on folks who are genderplural, though they don’t use the term.

How you frame a research question matters. A lot.

And the good news is that this, and steps like it, are helping to move the needle towards better research that’ll help nonbinary people be seen and heard for who they are.

As a non-binary transfeminine person, thank you. Another aspect of this bias I experience is the implicit biases in my own head telling me what I "should be" or "should do" in relation to what it means for me to be transgender. And it's so confusing and frustrating (and also frustrating trying to get across to people that non-binary != to androgeny). It's not just your bias from a binary standpoint,

it's my own fruatratingly binary bias as well having grown up in a culture that views gender as binary. And I would suspect a lot of non-binary folks experience a similar frustration.

Thanks again for another great, well sourced, and insightful article.

This is fantastic! I definitely saw how the cultural and scientific biases on transness gave me a fundamentally incomplete and flawed view of transness back in 2000 when I first started researching my trans identity. Even common words like "transsexual" at that time were (intentionally or unintentionally) exclusionary, but I didn't have the conceptual framework to see how.

As I aged, I continued to meet new people and try to constantly learn new things about transness and listen to people's experiences. Being in a support group that was 90% trans masc opened my eyes in a way that wouldn't have been possible in a transfem specific group, and once nonbinary people started joining the group I was forced to learn again.

I say "forced" because I was presented with new information. I couldn't ignore that information. Yet lots of people in the world do, all the time, because they're comfortable with the world being one set way. But I'm trans, and I figure that if I had given in to the "one set way" impulse, I wouldn't ever transition.

I find it fundamentally counter-intuitive to imagine a trans person, whose life is inherently about change and adapting to new concepts of gender, to be unwilling to adapt to new information about gender beyond their own circumstance. I understand why cis scientists and clinicians do it (not that it's right), but I don't understand why we do it. Is not growth beyond the norms inherent to being trans?

(Sorry if I'm way off, haha. I just get so tired of when I sometimes have to deal with enby exclusionists...)