Mujerísima… poses a bold new trans feminism for the twenty-first century and critiques the flaccid trans misogyny of the present in both anti-trans feminism and and queer and trans movements. Dissatisfied with the impotence of trans-inclusive feminism, which has proven unable to outmaneuver the trans misogyny of gender-critical and far-right anti-trans political movements, [mujerísima] turns to trans Latin America for a different lesson (p.26).

Everybody needs to read this book, I think. Everybody.

I lie on the softness of my couch, the evening sun warming my legs, and I clutch this short, little, green-jacketed book in trembling hands. Tears stream down my face as my eyes dance from word to glorious, breathless word in the conclusion of Jules Gill-Peterson’s A Short History of Trans Misogyny. It’s like Gill-Peterson distilled the living, thumping heart of my gender into a philosophy of feminism.

I drink in the words of the liberation I yearn for, the womanhood I want to scream from the rooftops, as though I were drowning of thirst.

B— checks in on me again from the kitchen. My sobbing is hard to miss, so it’s no surprise, but I wave her away. Anything to keep reading.

The last page comes, then the last word, each more wonderful than the last, and then it’s done. I close the book, hold it to my forehead, and howl with tears. I have never felt seen like this before, never been told these things before, and there simply are no words, no reality, that can possibly capture how much they mean to me. My body shakes and I cry and cry and cry and B— wordlessly comes over to the couch to hold me.

Some background

To say the least, I was deeply moved by A Short History of Trans Misogyny.

Mujerísima is a powerful call to arms, and the first truly transfeminine feminism that I’m aware of—but the reasons it needs to exist, the reasons it is so incredibly vital, aren’t obvious in a vacuum. Gill-Peterson lays it out for us in the conclusion to Short History, but when she does it, she rests it on over a hundred and thirty pages of detailed and thorough historical analysis, which stand as its foundation. Trying to understand mujerísima without a working understanding of the distinctions that Gill-Peterson makes in those hundred and thirty pages is basically impossible. So, before we can get there, we need a little vocabulary, and a little of the background that Short History covers.

First, the vocab. Some of these terms are going to be familiar to most of you, and are included here both for completeness and so that the differences Gill-Peterson’s work has with what you already know are more clear.

Trans Misogyny—When sexism and transphobia combine. This combined hatred, Gill-Peterson argues, makes its targets “uniquely killable,” by design.

Transfeminine—a person who is moving generally towards femininity or away from masculinity. An imperfect term meant to describe trans and nonbinary people assigned male at birth without referencing their birth gender.

Trans-feminization—When a person is assigned a feminine gender, gender role, or gender expectations without their consent. This has nothing to do with whether a person is trans.

For instance, when a relationship composed of two gay men is asked “so, who’s the man?” they are both being trans-feminized.

Similarly, when a nonbinary transmasculine person is treated as, essentially, “girl 2.0,” as many experience and complain of, they are being trans-feminized.

As a result, no person is trans misogyny exempt.

Trans Femininity—Femininity which is and has specifically been expressed, coded, or understood in a trans way, as a result of them being trans-feminized.

To be a bit flippant, “skirt go spinny,” is a perfect example of this, despite the fact that every little cis girl who’s ever worn a skirt or dress has done this just as much as any of us have.

Trans Woman—A trans person who understands themselves to be women.

Trans—A white, colonial amalgamation of gender diversity created in the 1960’s and 70’s and which really went global in the ‘80’s and ‘90’s, that set out to sever gender diversity from its historical contexts and meanings.

Many peoples were rolled under the trans umbrella without their consent—indeed, with their active objection—both the travesti of Brazil and Western Street Queens are examples of this.

The problem here is the melting pot problem; the amalgamation demands that people abandon incredibly impotant and precious personally- and culturally-unique traits to fit under a white, Western understanding of gender thats pretty much completely uninterested in their real, lived experiences.

The Grim History of Trans Misogyny

The core historical argument of A Short History of Trans Misogyny is that the global trans panic that we all are enduring now was the deliberate, calculated creation of European colonial invaders, who needed a moral excuse, a morality play, that they could sell to their citizenry to justify not only the invasion of the global South, but the ruthless, centuries-long exploitation and extermination of its peoples. The global trans panic has been ongoing for at least the last 250 years, and probably since the very stirrings of white settler colonialism in the early 1600’s. We are all, hopefully, pretty familiar with the unspeakable racism of the so-called white man’s burden, which argued that racist colonial exploitation was the method by which these “uncivilized” Black and Brown peoples would be remade into “proper,” white-coded, European-coded versions of themselves and their societies.

But what, asks Short History, made them “uncivilized” in the eyes of European colonists?

Drawing on extensive legal records from colonial India, the American Westward expansion, and elsewhere in the colonized world, Short History draws both from court proceedings and from laws enacted to systematically strip gender diverse targets of their manufactured hatred of their ways of life. Noting a number of other parallel instances across the global South more incidentally, Gill-Peterson argues that it was largely gender diversity that was the Western symbol for being “uncivilized” or “savage.” This was why Western clothing, for example, was so important to colonists, particularly in the Victorian era when these oppressions turned, typically, gendercidal.

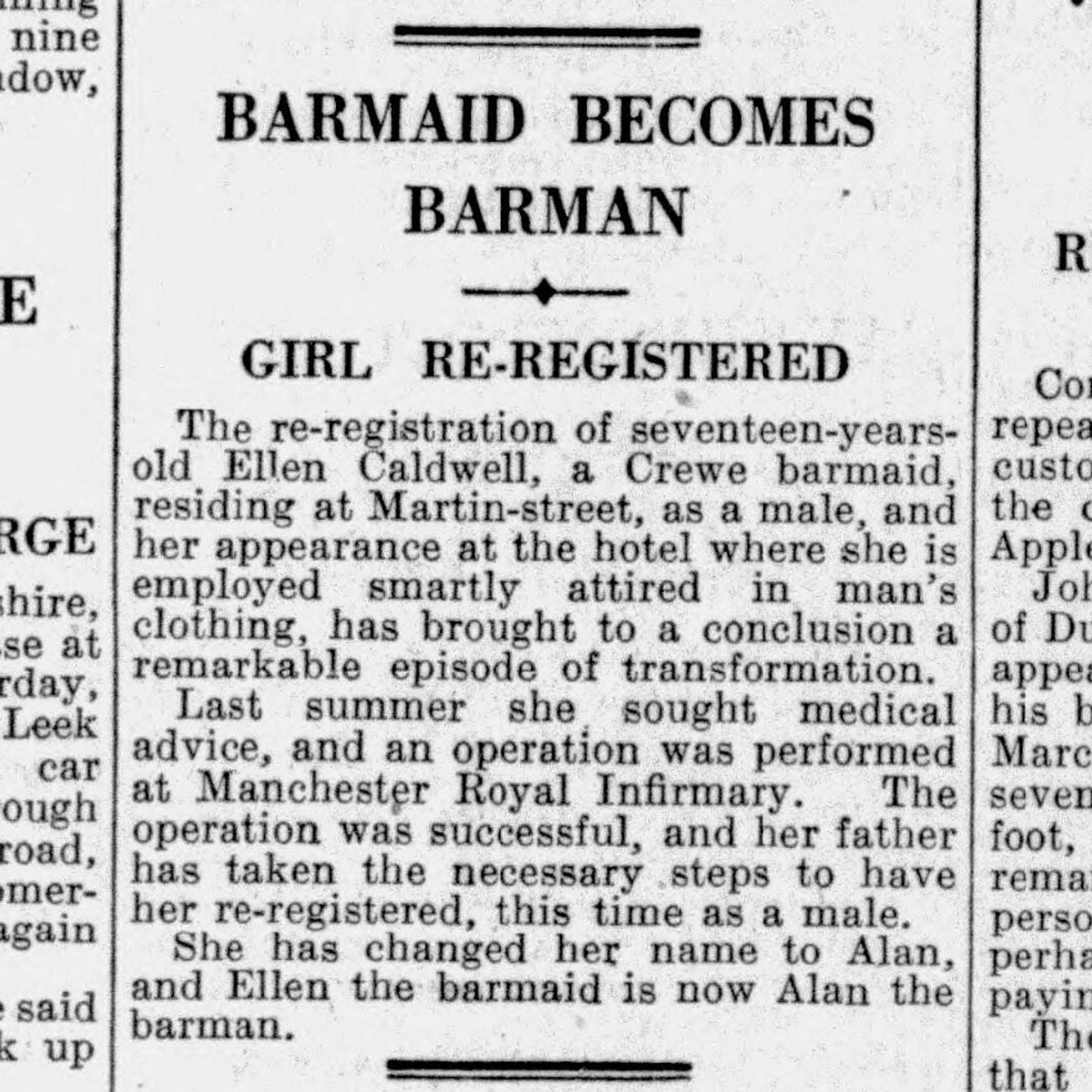

This move, and I cannot stress this enough, was entirely and completely manufactured. Before, and even during, the global colonial expansion, there was a large, well-known, and generally-well-tolerated gender expansive population in every part of the West. We know from historical records throughout Western history that trans and gender-expansive people were a normal and well-understood part of everyday life, from ancient times to medieval times, through the Victorian era, and onward to today. Trans people appeared regularly in newspapers and royal courts alike, their gender often mundane and unremarkable.

While trans people were often relegated to the fringes of Western society—transfeminine people far more so than transmasculine—and into sex work and the service economy, this division became far more ironclad during the Victorian era. With the rise of the Separate Spheres ideology, genderbending, queerness of all types, and even until-then-typical roles for, for instance, cis women as businesspeople were severely repressed. Arguably, this repression was trans-feminization itself, turned inward upon the societies that had used it as a tool for colonial domination, extermination, and extraction for a very long time. Before then, queerness was a fairly common and, if not enthusiastically accepted by the cishet majority, was generally pretty well-tolerated, to the point that nunneries, for centuries, had very a strong cultural subtext as hotbeds for rampant lesbianism.

Unfortunately, Western colonists were largely successful in their efforts to exterminate third-gender people and gender-expansive cultures, both at home and abroad. While a number of these people, like the hijra, survive to this day, their traditional ways of living, of being, their cultures, and even their common understanding of themselves as a part of a gender trinary were all but obliterated. To quote directly:

By the early nineteenth century, the global reach of European and American slavery and colonialism had stolen so many bodies, and severed so many people’s relationships to the land, that the urban, lumpenproliterian model of trans womanhood began to replace all others (p.92).

This, Gill-Peterson argues, is why trans panic—a panic in response to trans femininity— is so strong in so many places. It was the harbinger of and the justification for literal genocide for centuries, and old memories of such massive societal trauma run deep. That’s why many, but not all, cis, heterosexual white men fight to enforce it even today. The continued extermination of trans women is, at heart, the justification for white, masculine power.

And that’s why trans-feminized people are “uniquely killable.”

It’s not that trans people are a recent development. It’s that we were systematically exterminated until very recently.

Anything you can do…

One of the hardest parts of facing this history of global geno- and gendercide aimed, specifically, at trans people is that we must also face the grim reality that there’s very little we can do to recover what was lost. Culture is a living, breathing, growing thing, and like any living thing, when it is killed and left for dead, it remains dead. Revivals, at best, create something new and different, not that-which-once-was. It’s why efforts to keep Native languages alive, in regular use and in living memory, are so vital.

And it’s why Blackness exists, in comparison to having German or Irish heritage if you’re white. Once the cultural violence is complete and your heritage is dead and buried, recovering it is… well, if regional Black-African cultural traditions vital between the 1600’s and the 1800’s could be effectively revived by the descendents of those the white West kidnapped and tortured, they certainly would have been. Instead, as Gill-Peterson argues, it is much wiser to take instruction from other survivors of colonial extermination as we, as trans people, work to find our own sense of place and culture in a world that does systematic violence to us to this day.

And it’s not just violence from the political right, from trans-exterminationists who carry the modern flag of racist colonial systems. Our erstwhile “allies” to the left generally imagine a future in which gender is an irrelevancy, reenacting the melting pot fallacy on us again. It is… frustrating, to say the least, when those “allies” fight for “a world in which trans womanhood is implicitly obsolete, no longer needed in gender’s abolition or an infinite taxonomy of identities beyond the binary (p.135).” It is, ironically, the one thing that both the right and the left generally agree on: “trans femininity is not integral to the future they are fighting for.”

The core problem with white feminism is crystallized in this simple little ditty from Annie Get Your Gun! that’s since become a touchstone for little girls: “Anything you can do, I can do better. I can do anything better than you.”

Since the beginning of second-wave feminism, white feminists have pushed toward a single end, though they haven’t generally admitted it: the end of womanhood as a category. In many ways, it’s the original sin of modern feminism, tracing all the way back to Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, which is built from the ground up on its classification of ‘woman’ as ‘the marked sex,’—remember, at this time, sex and gender were exact synonyms in English—while man is unmarked, default. Ever since, white feminism has worked to escape the mark of that gender, not to tear down the system that marked it.

The system that thinks of femininity itself as disposable.

It’s why the key goal of each step in the feminist struggle has been, yes, towards equal rights, but in the form of doing the things men do in the way that men do them. “Breaking the glass ceiling,” for instance, does nothing to address the fundamental inequalities that caused the glass ceiling to exist in the first place—and continues to exist, at a much lower height and tempered with much greater strength, to resist Black and Brown women, who white feminists usually pay no mind to.

And at every step along the way, these white feminists have done so by rejecting, demonizing, marginalizing, and trying to exterminate femininity, and particularly trans femininity. This was ultimately the core argument of Whipping Girl: that white feminism is the same old gendercide, just wrapped up in pink ribbons and pantsuits.

That’s why Gill-Peterson calls both trans-inclusive and trans-exclusive feminism “flaccid.” Both versions ultimately support the fundamental caste structure that the racialized colonial cisheteropatriarchy we live in has built over the last several hundred years, and are just jockeying for a place higher up on it.

Under constant assault from both the left and the right, how can trans feminine people, trans women, people for whom trans femininity is not only important but vital—how can we even begin to put words to this glowing ember inside of each of us, which has survived millennia and the raging extermination of generations?

Traduttore, traditore

There’s an old Italian phrase that I love for its delicious irony: ‘traduttore, traditore.’ It has a fair bit of cultural context, but it more or less translates, variably, as ‘translator, traitor,"‘ ‘to translate is to betray,’ or ‘translators are traitors.’ The difference between those three interpretations of the phrase shows us the exact, specific point that the phrase is trying to make: that there is never a direct translation for anything, because all words and phrases, and especially idioms, have a lot of cultural context that’s impossible for any translator to capture. This idea is important here because the answer that Jules Gill-Peterson offers to us to the problem of trans feminine cultural and practical survival is a word, untranslated.

Mujerísima.

It can’t be translated directly. It’s a word, a philosophy, which has been used among the travesti for a very long time, so it’s got a huge amount of both historical and cultural context. That said, many of us don’t have that context, or even the Spanish to make the word literally intelligible. So, I offer here only a simple translation, and the acknowledgement that it is woefully inadequate:

Mujer—A woman.

ísima—a modifier that can be added to a word to indicate that it is maximal, extraordinary, unmatched and unmatchable.

Together? They mean something like “maximalist womanhood.”

And there’s an important note here: mujerísima is about maximalist femininity, not maximal femininity, which is already something else. Related, I suppose, and that approach could certainly be thought of as one type of mujerísima, but that’s not its objective. Mujerísima doesn’t aim to celebrate the girliest girl who has ever girled a girl—the philosophy is about celebrating femininity, and specifically trans femininity, loudly, forcefully, proudly, and unabashedly. Femininity is just as much torn fishnets or plaid punk skirts as it is Barbie pink dresses and petticoats, and no version better or more feminine than the other.

Call it roller derby feminism if mujerísima feels like appropriation, or if just the term “maximalist femininity” feels like a bad fit with your nonbinary gender. I don’t know if Gill-Peterson would care for the term, but I really can’t think of anything more loudly, aggressively, unashamedly, fleshily, and sensually feminine than roller derby.

Post-scarcity feminism

We know that trans cultural visibility and its liberal politics thrive on the disavowal, theft, and destruction of our ways of life, and of our dreams. We know this happens especially when we are most visible, at the center of other people’s thinking and activism, or even their central concern. When movements claim to act in our name, or use our image as their rallying cry, it is often to imagine a world where trans womanhood is implicitly obsolete, no longer needed in gender’s abolition or an infinite taxonomy of genders beyond the binary (p. 135).

This is the truth universally-understood by every transfeminine person, even if we never say so. Black women activists have seen the same effect for the longest time too, as their own identities and struggles intersect and parallel the trans and queer rights movements. All of our womanhood is conditional. On sufferance. Revocable.

White cis, straight women hold the reins of power, and they use those reins to both define the limits of womanhood and femininity and to conserve it from those less white, cis, rich, and straight than they are. When you hear a million white women on Facebook chant “trans women are women,” they’re not saying “womanhood grows with the inclusion of trans women.” They’re saying that “trans women are woman enough to be counted amongst our number, if you peel away the things that make then unique.”

Lesser. But acceptable. In the same way that Black femininity and feminism was eventually, grudgingly, accepted into feminism’s fold. And Latine feminism and femininity. And East Asian. And, and, and—you know the rest.

That our excesses and exuberances are tolerable.

That if we shrink our quirks enough we may be counted amongst them.

It’s the melting-pot fallacy all over again.

Fuck.

That.

Noise.

Trans women are extra. Trans femininity is too much. The first mistake of any trans-inclusive feminism is to confine itself by flattening what makes trans femininity and womanhood different from the generic [white] standard. Championing the inclusion of trans women by saying that they are indistinguishable from non-trans women is the product of a scarcity mindset. So, too, is claiming that trans femininity has a stable definition or that trans femininity fits neatly under the trans umbrella, or even the LGBT umbrella. Their assimilation into a whole is always a concession to the fear that there isn’t enough to go around (p. 141).

For hundreds of years—ever since the Victorian era, and by some measures for even longer before that—femininity and womanhood have been jammed into a scarcity mindset. The idea that womanhood or femininity must be protected from assaults from the outside, from the ravening hordes of the uncivilized, is a racist, settler-colonial myth that was created to murder and kidnap millions and millions of people and steal their homes from them.

And worse. So, so much worse.

Scarcity mindsets call back to our cultural pasts, when we had to face the constant fear of running out—running out of food, of shelter, of water, of family, of all the things that make living possible. Many of us have scarcity mindsets taught to us when we’re barely out of the cradle—”clean your plate, because there are children in China/Africa/South America/insert-colonized-and-exploited-location-here who are starving.” We learn at once to fear that there will never be enough anything, and that it’s okay for us to gorge to bursting at the cost of others starving.

And that it’s okay for us to horde what we want at the expense of others. To deny to them what is vital for all of our lives. Never mind that we already make enough food—enough everything, really, but let’s stick with food—to feed 1.5 times the world’s population. That for decades, governments have literally paid farmers with arable land to not farm, because there’s already too much.

But femininity, like all abstract concepts, is inexhaustible by it’s very nature. If a billion girls are born, the femininity we all have isn’t depleted. Far from it.

It grows.

And trans women, mujerísima argues, should not merely be accepted into femininity’s circle—we should stand at its very center.

What if feminists didn’t reply to the charge that trans women are too sexual, or too feminine, by shrinking trans women to prove the accuser’s bad faith [argument] wrong? What if trans feminism meant saying yes to being too much, not because everyone should become more feminine, or more sexual, but because a safer world is one in which there is nothing wrong with being extra?… What if trans feminism dedramatized and celebrated trans femininity as the most feminine, or trans women as the most women? How might trans women lead a coalition in the name of femininity, not to replace or even define other kinds of women, but to show how the world might look like for everyone if it were hospitable to being extra and having more than enough (p. 143)?

Who, on Earth, fights harder for womanhood, for femininity, than trans feminine people? Who loves and needs and vibrates with the quivering need to be feminine, woman, more than transfeminine people? Who celebrates every conceptual atom of femininity and womanhood more utterly than trans women?

To whom, in all of existence, does womanhood mean more than to us?

This is the heart of mujerísima.

Womanhood is not white womanhood. It is not cis womanhood. It is not straight womanhood. It is not Western womanhood.

It is those things, for those of us who are white, or straight, or Western, but it is far, far from being only those things. It means so, so much more, and we should not—cannot—allow white, cis, straight, Western womanhood to monopolize what it means to be a woman any longer.

If trans women and trans feminine people embrace our bodies, our sexualities, our femininity, more loudly, unabashedly, and more expansively than other women—cis, white, straight, wealthym Western women, who clutch their pearls and worry about the goddamned optics—it is because we know the value of every immeasurable iota of that gendered glory. And seeing us drink deeply and with such vibrant joy of the very femininity that they’ve worked for so long to abolish in the name of their own personal power unsettles white feminism and transphobic regressives in equal measure. Obliterating a level in a caste system is possible, but there can never be two truly coequal ways of being, because the entire justification for the caste itself is to conserve and exercise power. For there to be a strict, viciously-enforced hierarchy, where those above can exploit and abuse those below without fear or consequence.

Equality—real equality, not whinging claims of it—is anathema to any caste system.

And it is here that A Short History of Trans Misogyny turns fully to the lives and experiences of the travesti for instruction not only on what form genuinely trans-inclusive feminism should take, but how we can accomplish it without falling into the same trap of singular thinking—the idea that there is one right or best way to be.

To be, in our case, trans.

Mujerísima underlines a fierce commitment to being unabashedly the most feminine, or the womanliest of all, in a loudly travesti way, manifestly different from the normative [white, Western, cis, straight] ideal of womanhood. Mujerísima is a part of the travesti rejection of assimilation, including to transgender womanhood (p. 145).

Emphasis mine.

Strange as it may seem, the maximalism of mujerísima fits into the modest principle of lo suficientemente bueno [Note: for the reasons stated above, I offer no translation here, but Gill-Peterson uses “the good enough”]… Instead of medical gender identities or legal recognition of LGBT citizens, [the] good-enough questions for organizing are simple: “Why do we have to live everyday with fear? Why do we have to go home afraid?”… [It] imagines the work of convivencia—living peacefully across difference, where collective flourishing doesn’t require the adoption of a singular model and its imposition on everyone. Travesti politics… are about what’s good enough for everyone, not perfection for some and suffering for others. [It’s about giving] up the quest for the perfect language, or law, to govern identity. The good enough keeps us present, attuned to what is here in the world, instead of asking to wait for our reward until we find perfection or utopia (p. 149-150).

Again, emphasis mine.

White and queer feminisms have a… grim history of celebrating symbolic victories and pretending that they really matter in some sort of intense, universal way. “The first woman this,” or “the first gay that,” or even “the first trans such-and-so,”and yet here we sit, in 2024, facing a regression in basic human rights in the United states and rising misogyny, queerphobia, and fascism in many places around the world. Or, in more practical terms, the wealthy and powerful in our community—and by any reasonable measure, I must count myself among them, as a financially- and socially-secure professor—enjoy physical safety and the transitions of our dreams while so many of us are forced to flee their homes for their safety, or struggle to lay hands on the hormones that we rely on for our very survival.

By white feminist standards, my story is a triumph. I see it as a tragedy. Everybody deserves the level of care I got.

Everybody.

My transition didn’t really change much for anyone else. What I did with it? This newsletter? That’s my best effort to give back to the community that’s given me so much, and has allowed me to become who I am. But my transition itself, the access to world-class surgical care that I had because I had the money and education and training to fight for it? That helped me, not the rest of the community.

And that fact enrages me.

But beyond that, I find myself raised up with that privilege in no small part because I fit a particular mold—white, feminine, curvy, well-spoken, passionate without being too obviously radical… you know the rest. When people see me, they see a very traditional transfeminine look and mode we’ve all been trained to look for, all the way back to Christine Jorgensen.

Put a different way: why are you here, reading my work, not the work of the—in her own words—Brown trans woman who actually wrote the damn book?

Maybe think on that a bit. And remember: the parts of me I mentioned above? They’re far, far from the whole of me.

There will never be one way to describe gender diversity that really accurately describes us all. There will never be one way of being, or living, that meets everyone’s needs. Fighting for, demanding, expecting that idealized perfection is to shred any hope that there will ever be a good enough life for each of us. And that means that a good enough philosophy of feminist maximalism—mujerísima—needs to embrace what it means to be queer, at its deepest heart:

Failure. Fallibility. Idiosyncracy. The kaleidoscopic, infinite variability of what it means to be feminine, to be woman, to be trans, where none of them is better or more desirable than any other, and where each of them is celebrated and loved and supported.

We don’t rise when one of us rises. We rise when all of us rise.

Femininity is the reward, here and now. Sexuality signals its arrival in the fleshy present. Heaven is already here on Earth, growing with each demonstration in the streets and each ceremonial commitment to the sanctity of travesti femininity in shades richly Black and Brown, linking with the struggles of non-travesti women who have been policed by misogyny and racism. Strangely, wondrously, the travesti politics of the good enough, though they set aside the impossible threshold of perfection, are nothing like pragmatism. What’s good enough is not predetermined or static, which means it has no limit. What’s good enough can grow and change over time, without a prescribed end, meaning it can deliver on the vastness of mujerísima. What proves to be good enough for travestis, for trans-feminized people around the world, and for the divinity of trans femininity itself, is nothing less than the most.

Will you demand it all (P. 153-4)?

I actually did read the book a couple weeks ago, but I got a great deal more from your interpretation than from her book. (Although people should definitely go read "A short history of trans-misogyny".

I'm a white trans woman from Oklahoma who spent 9 of the last 11 years in Latin America and the first year of my transition in Colombia. I just moved back to the US in January to get access to the world class gender affirming care that should be available to everyone.

So when I read her book, I was already quite familiar with the concepts in the last third of it. But I failed to connect them to white American culture because I haven't been a part of that for so long. Now I’m trying to re-integrate into white culture but I’m just constantly too “extra”. Not just in my gender, but in everything. That was fine in Colombia where everyone is extra, but it’s rough in the US where white culture always wants me to be less in basically every way.

So I’ve been making myself small, mousy, etc… Trying to fit back into white culture, white queerness. But I feel Latina in my soul. The same way I have always felt woman-ness in my soul. Your post just rocked my world, because it makes me wonder if “it’s ok” to be Mujerísima, Latina, etc… All of me, all the extra bits… Exactly who I feel that I am in my innermost being.

And maybe I don’t need to make myself small for anyone, or any culture. And maybe this is an idea worth spreading.

Bought! And will be read. A longer read, but I also commend "That's Revolting! (Queer Strategies for Resisting Assimilation)" from Soft Skull Press in Brooklyn 💥