Transition Timelines

The long, slow tail end of hormonal transition when you're an adult

I sigh, staring into the mirror, and try to not be disappointed.

I’m at just over two years on HRT, and the January snow in Michigan is just now really starting to come down. A proper Michigan blizzard, it’s got the whole city shut down, and B— and I are tucked away at home, enjoying being snug and unable to do a thing of consequence. Or, trying, in my case.

A conference I’m really excited about is coming up soon, and it’s going to be the first time I’ll be out in public in a big way without my hairpiece, so I’m finally taking a really long, careful look at my face, still healing from my facial feminization surgery but now very well into its healing phase. I look good. A million times better than I did when I started transition, but just… not really what I’d secretly hoped for. The last two years of my transition has been an absolute frenzy of work, desperate to get everything I possibly can out of my hormonal transition before—

Well, before the two-year mark.

I’m a scientist. Scientaster, perhaps, since what I do is report, rather than research, but still. I did my research. Everything I can find says it pretty clearly: expected results for virtually everything in estrogenic HRT will be seen by 24 months from the start of hormonal transition. It’s loomed in the back of my mind for the last two years, a ticking deadline I’ve felt like I can’t escape.

A deadline three months past, now.

B— has noticed my melancholy, but I’ve always smiled and told her it’s just impatience for my FFS recovery to be over and done with. That’s not even a lie—I am impatient, quite impatient, but it’s also not the whole story. My face is just the most prominent part, but my breasts never really came in, and the hips and butt I’ve got are… not exactly up to the excellent standard other women in my family seem to all get without an ounce of effort.

I skate for fitness. Hip and butt implants aren’t options for me the way breast implants are, and I’m just not comfortable with the safety of Brazilian Butt Lifts.

I guess this is it, I think, and smile at myself. It’s only a little forced.

I stare into the mirror, smiling wholeheartedly. It’s a little more than three years of HRT now, and I can’t get enough of the girl smiling back at me from my reflection. It’s not just my face, either. My butt has grown enough that some of my pants from last year are on the verge of not fitting, even though I’ve lost weight, and my hips are finally starting to look like they belong to a woman from my family. The last year has been equal parts wild and wonderful, but one thing’s for absolute certain:

24 months wasn’t the end of HRT’s effects, that’s for damn sure.

The thing they tell you when you start HRT

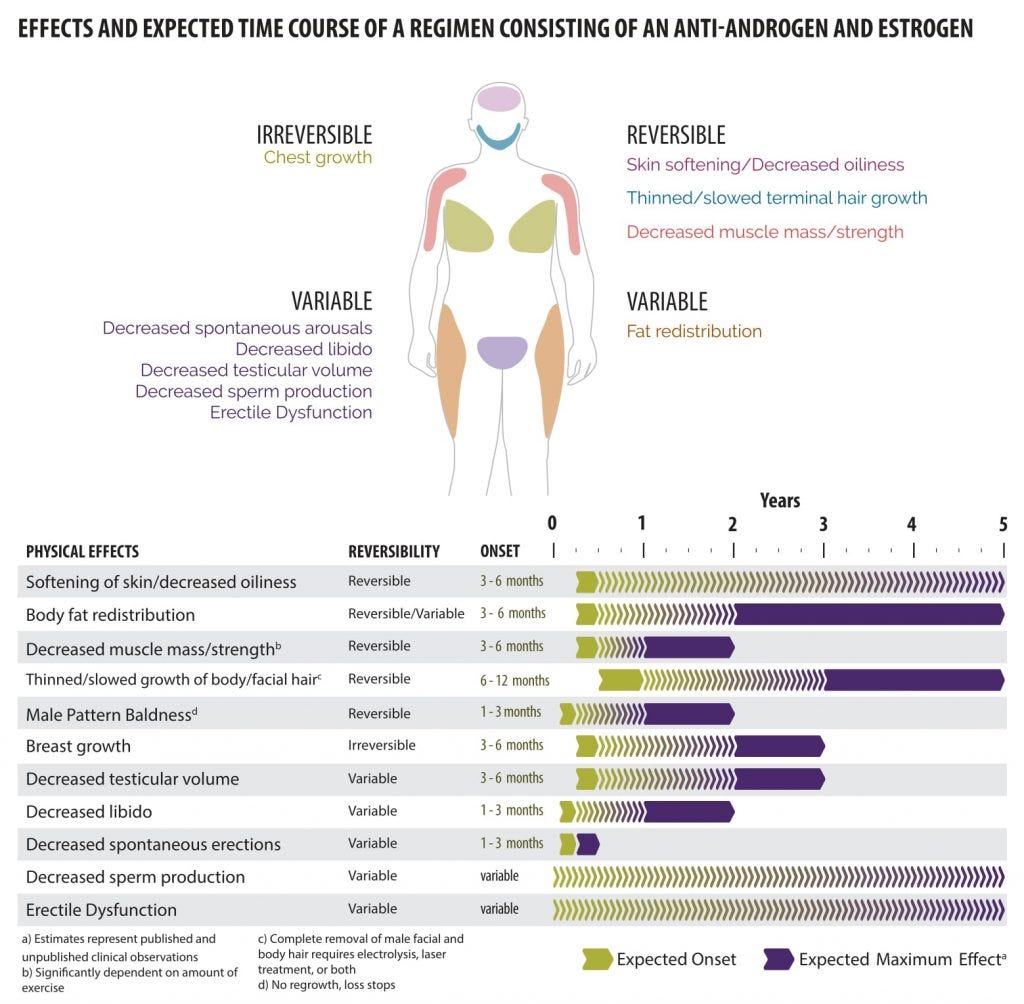

When a trans person begins HRT, the prescribing doctor sits down with you and runs through an absolute laundry list of what you can expect from it. If you’ve started yourself, you probably remember—there’s usually a packet and diagrams and stuff. Sometimes, they’ll even show you a graph, like one of these, courtesy of Transgender Care Montcalm:

They’re good graphs. Clear, it’s easy to visually nab all of the information. And those talks, at the start of HRT? The absolute foundation of informed consent.

It’s a shame the information in them is bullshit.

I mean, it’s not all bullshit, and I don’t want to imply that the doctors presenting this information are acting in the wrong. They’re not! The listed effects here are indeed correct for how testosterone and estrogen will affect the human body.

But that list isn’t complete.

And it includes information we know stone cold to be wrong. No hair regrowth on estrogen? That’s hilariously wrong. I mean, this is in the scholarly literature as an example of estrogen-only hair regrowth, with only six months separating the before and after:

And the timeline? It’s pretty much medical-grade nonsense.

And it’s all because of how HRT has been studied.

Cis focuses, cis results

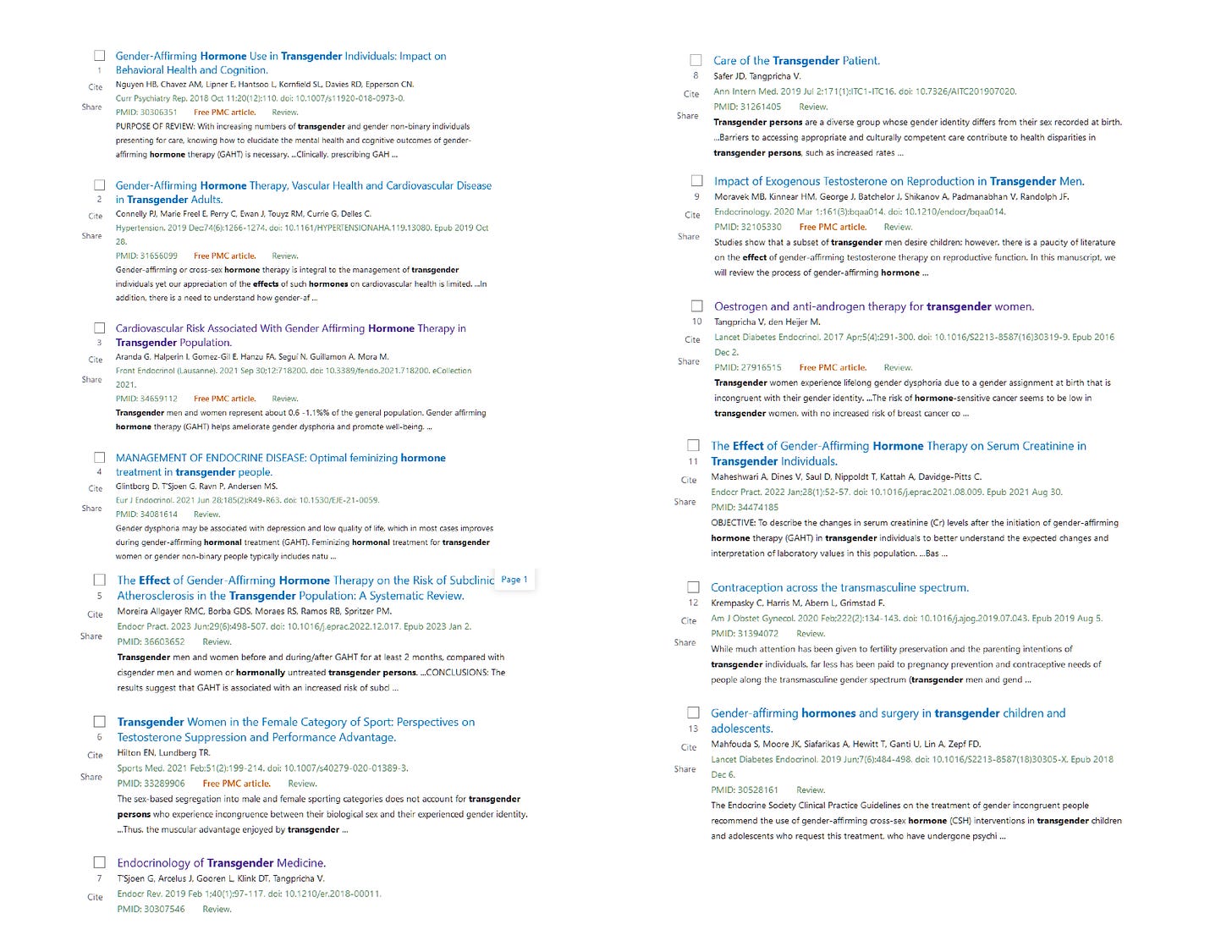

There’s been a lot of research on how HRT affects trans folks. Like, a lot a lot. Thing is, though, when you look at how HRT has been studied, there’s a clear and overwhelming focus.

I do most of my research for Stained Glass Woman through a database called PubMed, which is a US-government-administered platform that archives all medical and pharmaceutical research done in America which was funded, wholly or partially, through US government grant money. For reference, that’s the overwhelming majority of all medical research, and the stuff on PubMed is pretty much always freely accessible for anyone to read for themselves. It’s a powerfully searchable database, and it lets medical researchers do incredible things with our scientific research.

When I look for “transgender hormone effect,” just to pluck one search term out, here’s a sample of the results I get:

Of the first 13 results for a simple search on the effects of gender-affirming hormone replacement therapy on PubMed, only four or five, depending on how you want to consider the 13th one (as it’s as much about surgery as HRT) are actually about the overall effects of HRT, and none of them are research on the timelines or desirability of the effects of hormonal transition.

None of them.

No matter how you search PubMed, the overwhelming majority of the results you’ll get when you research transgender anything, but especially HRT, focus on the risks and disasters we might face as part of our hormonal transitions.

And even the ones that do speak to how to help care for us overall?

Well, I’ll let these samples from their abstracts speak for themselves:

In a nutshell? Cis researchers overwhelmingly study risks, to the near-exclusion of research on the actual desirable effects of HRT. It’s so egregious that some of the main studies on the desirable effects of HRT, which continue to be cited today, are from 1989 and 1986. Fair warning: those articles talk about trans people in ways most of us would feel are pretty monstrous today.

So, what’s the deal? Why are cis doctors so obsessed with risks?

Trans broken arm syndrome

Stop me if you’ve heard a variation on this one:

A trans person falls while exercising and hurts her arm. She goes into urgent care to get the wound treated at urgent care. The doctor comes in, looks at her bleeding and maybe-broken arm, and comments that she’s got a fair bit of road rash, but does so using he/him pronouns.

“No, doctor,” she says. “I’m a transgender woman. My pronouns are she and her.”

The doctor blinks and shifts uncomfortably on his stool.

“Have you considered that your hormone replacement therapy might’ve been part of the cause for this?” he asks. “You should probably stop it.”

There’s a long, awkward silence in the exam room.

“I’m not on HRT yet,” the woman says. “And how would estrogen make it more likely that I’d fall?”

Another, longer silence.

“I’ll send in the nurse to clean your wound and take X-rays,” he says, and leaves.

That actually happened to me, in late September of 2020. A rock caught in one of my skates and I took a spill, and the doctor at urgent care literally told me that the HRT I wasn’t even on yet had caused it.

Trans Broken Arm Syndrome is when physicians near-obsessively and intrusively focus on all of the possible ways that a person could have some sort of bad effect as a result of their hormonal transitions. Many of them do so with absolutely zero meaningful understanding of what HRT is or how it works, often inventing wild theories on the spot to justify their prejudices. According to the research, it’s extremely common, and it seriously undercuts the care trans folks receive.

Thing is, Trans Broken Arm Syndrome isn’t just limited to urgent care, the emergency room, or a primary care doctor’s office. The brute truth here is that most doctors are cisgender, and they look at their trans patients and are, at a gut, emotional level, confused as to why someone would do what we’re doing. They want to know how and why it can go wrong.

And good god, do they want to tell us exactly what they find.

We call this sort of attitude physician bias or, in the case of medical research, researcher bias. These doctors, these researchers, aren’t even aware that they’re prejudiced against us.

But that prejudice influences the research that they do.

Why it’s “two years”

All of this comes together to a pretty simple point: since almost all of the research that’s being done on trans folks is about risk management, what we know for how HRT affects a trans person over the course of our lifetime is very limited. We’re stuck using very old, outdated research that was done with versions of hormones that we don’t even use anymore, on very small groups of trans participants, when our very understanding of what it means to be trans has completely changed in the meanwhile.

Let me repeat that, just for clarity:

When most of the research on the effects of HRT was done, the researchers thought of us, and treated our bodies, as though we were and would forever be members of our AGAB.

And that’s the research that is still cited today.

And the research that does get done on us? Virtually all of it only lasts 1-2 years.

You remember those unfortunate timeline graphs from earlier? Here’s the reference page behind the feminizing HRT one:

I’ve highlighted a few things, obviously. Look at the range of those publication dates. Some are as old as I am, and only five of them were performed in the last decade. These aren’t lazy providers, for clarity! They’re doing their best! The focus on our health is just that bad. Take this study on progesterone, for example—it set out to see if progesterone affected breast growth in trans women… and ran for three months. On nineteen participants. That’s a ludicrously small sample and time period.

That, coincidentally, kind of brings us to the point: I’ve said a whole bunch that all science has a half-life, right? Well, back when most of the “recent” research was done on the effects of estrogen and testosterone on trans people, “the duration of puberty was [thought to be] 1.96 +/- 0.06 years” for cis girls, for instance, and a similar length for cis boys. In the last twenty years, however, a lot more science has been done, brying that window wider and wider, at least doubling that length, now, strong data says that puberty lasts around 10-14 years. It makes sense that doctors studied HRT the way that they did. When they did it, they thought that that was as long as puberty lasted. That part just… turned out to be wrong.

Simply put: trans folks are a marginalized, oppressed group which relies on the dominant group to research our medical needs. We, in general, don’t get a say in the research done on us, and it’s why I haven’t—and won’t—write an article about best practices on HRT that’s more specific than “stay within either male or female ranges, or work with an endocrinologist to find a nonbinary combination of estrogen and testosterone that’s right for you.”

We don’t have the research data.

And frankly? It’s not coming. I’m not aware of any meaningful, long-term research that compares different methods, doses, or approaches for HRT that’s currently in process.

Part of me can’t blame researchers. Running a single study for a decade and a half on any reasonably large sized group of people? That’s basically making that one study your entire life’s work, and it’s something that’d be incredibly expensive to do.

But it means that we’re going to be out in the wilderness for what HRT does after the first two years for the foreseeable future.

What we know, and what it means

All of this means that we have to move forward based on general knowledge, not specific research information. And that knowledge, in the end, boils down to this:

Starting a hormonal transition is, fundamentally, starting a second puberty.

Puberty lasts between 10-15 years.

Pubertal changes are affected by a person’s metabolism.

A person’s metabolism slows down as they get older.

Puberty’s effects toward the tail end tend to be subtle individually, but really significant in total.

A great example here is how a young man’s upper body frame fills out when he hits his early twenties, taking him from a scarecrow to the suddenly-robust arms and necks that you see so often.

And that means, all together?

Settle in. You’re going to be seeing changes from your hormones for a long, long time.

Thank you for this breakdown. Even if the conclusion is frustrating, I think it is a really useful explanation for those of us still in the first few years of transition and for us to share with loved ones who have genuine concerns.

The amount I've gotten out of HRT compared to what I was initially led to expect has been nothing short of astonishing. It's easy to get ideas in your head through osmosis from transphobes, like that hormones basically do nothing, but the reality is damn near magical.