I shift in my mesh office chair and bite my lip, the hair of the little topper wig I’m wearing tickling my cheek. It hides my receded, nightmare hairline. In front of me, on the left of my two monitors, is dozens of little rectangles, showing person after person in the virtual gender support group my therapist had encouraged me to attend. The facilitator is an older lady who said she’d been in transition for over nine years now, and she’s encouraging and soft-spoken, two things I’m intensely grateful for right now. There are, maybe, twenty or twenty-five people in the meeting with me, and they’ve been taking turns to talk about their struggles and triumphs as trans folks.

They have, anyway. My mic is off.

My camera is off too, of course.

The woman speaking now seems impossibly beyond me. Not the facilitator, and probably older than I am, but she’s lovely in the way that women get when they hit their late middle age, where wrinkles start to appear to tell tales of kindnesses given and struggles overcome. I can’t imagine ever being as beautiful as she is as she recites her poetry for us all. As smart, as strong.

My heart sinks, and sinks, and sinks.

I’ve known I was trans for all of twenty-seven days.

I’ve known I was a woman for nineteen days.

I made an appointment to start HRT thirteen days ago. Less than two weeks. An appointment that won’t come for almost two months.

I shift, my pleated skirt shifting with me, and I love it’s kiss on my knees. I feel like a fraud. My heart sinks further.

I haven’t dared to say a word at this meeting, and I’m increasingly sure I don’t belong. Won’t belong. Can’t belong.

It’s been two hours, and now the facilitator is calling an end to the meeting. People are leaving, and my opportunity has passed. I wait, as they file out, and tap out a private message in the text chat to the facilitator to thank her for allowing me to join them. Soon enough, almost everyone has gone—it’s just her and me and a couple of transmasculine people who, I will learn many weeks later, are also facilitators.

“I’m glad you came,” she says to me over the video, smiling at my blank, silent screen. I type out a reply as quick as I can that it was very nice of her to let someone like me, who doesn’t belong, come.

“You’re welcome any time,” she says warmly, and it’s too much. I can’t just go, not when she’s being so nice to me. Obviously, she doesn’t understand. I start typing again, but before I can send anything, she says “It’s just us, you know. You can turn on your mic and camera if you want.”

I pause. I hesitate.

I unmute my mic.

“Sorry,” I say in my awful man’s voice. “I just…” but the words are gone, whatever it was I wanted to say. I’m withering, so ashamed to be taking up their time when I don’t deserve it.

“You don’t have to turn on your camera,” she says, repeating something she’d said earlier. I hesitate again.

“Fuck it,” I say, and turn my camera on. My beard shadow, poorly-hidden behind cheap foundation applied too heavily, slashes across the screen. I look like a scared buck, badly and comically disguised as a doe.

“Hi, there!” she sais cheerfully, and the two others give me little waves. For some reason, they’re not laughing at me. They’re treating me like…

Like I belong here.

I can’t say how confusing it is. How hopeful. How impossible.

“I’m Zoe,” I say, for want of anything else to say, and I realize afterward that it’s the first time I’ve told a stranger my name.

“It’s nice to meet you, Zoe,” she says. “Welcome.”

On being trans enough

The trans experience is incredibly, impossibly diverse. Over the years I’ve been out, I’ve met more trans people than I could even guess at, with more experiences, more genders, more perspectives than I could describe if I took the rest of my life to try and catalogue them. Each is spectrally different, and impossibly so, in ways that, sometimes, aren’t even within the bounds of physical human possibility.

I don’t even understand a lot of their experiences of gender. Doesn’t make those experiences any less or more real than mine, just… beyond my ken.

To be honest, it’s one of my favorite parts about the trans experience. Sit two trans people down in a room and ask them to talk about what their gender is and what it feels like to them, and you’ll get the most wonderful, poetic responses, from the starkness of “just a little guy” to “the triple point of woman” to “a tachi-class combat doll,” with a mythos that spans cultures and whole novels to contextualize it.

It’s fucking cool.

In all of that variation, one thing I like to say is that “there’s no one way to be trans,” meaning that each of our experiences is unique to ourselves. There’s nothing that each of us shares beyond the desire to be a gender that isn’t our gender assigned at birth.

But… well, I don’t think that’s entirely true. Not quite. Because there’s one other thing I’ve seen at some point in every single trans person I’ve ever met. Something they either confided to me, raise as a possible reason that they’re might not even be trans, to the bemused, self-depricating memory of times past.

And that’s the feeling of not really being trans enough.

Of being an imposter.

Imposter syndrome

I’m sure most of you have heard of imposter syndrome at some point. On the off chance that you haven’t, it’s this thing that happens when someone believes that they’re not as [insert trait here, usually smart, capable, or competent] as other people around them, that they’ll be discovered as a fraud in short order, and that that discovery will lead directly to abject, total failure. The thing is, imposter syndrome isn’t connected to reality at any level—the reverse, in fact! Scientists are some of the people who experience imposter syndrome most frequently, for example.

And yes, I experience it too.

Imposter syndrome isn’t a formal diagnosis, like depression or anxiety. It’s a common, shared experience, and it’s seen some pretty decent study, mostly as part of employment and professionalization research. The thing is, members of minorities in general and queer folks in particular experience imposter syndrome at rates much higher than average, though there’s some chaos in those numbers. Not much research has been done, specifically, on queer folks’ feelings of imposter syndrome on their own queerness, let alone on trans people’s.

But the research that has been done tells us a lot. Specifically, where imposter syndrome comes from.

Being not good enough

Imposter syndrome has been studied the most in doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other medical workers, partially because it’s a little easier to get access to members of those professions to participate in studies than many others. Imposter syndrome comes from a fear of imperfection, and a drive to perfectionism, which I’ve written about a few times before as a devastatingly harmful pillar of white supremacy that pervades Western society generally. The thing is, though, it’s not perfectionism itself that causes imposter syndrome.

No. It’s when that perfectionism, or rather the drive to be perfect, is combined with a fear of not being able to meet other people’s expectations of them:

Although the health professions students we sampled did not report more perfectionism than other student samples, as we had expected, we still found that the students who were very perfectionistic were at signifcantly greater risk for psychological distress. In particular, students who were chronically worried about meeting others' expectations of them reported more psychological symptoms.

Masking, in other words—when we suppress ourselves to meet other people’s expectations of us. And masking our queer genders and sexualities has long, long been observed as one of the most common ways that people feel imposter syndrome.

It’s absolutely everywhere. And I’m far from the only person who’s written about it.

But why is queer masking and perfectionism so common in queer folks, and even moreso in trans folks?

The tiger in your home

A little while ago, I wrote a bunch of articles on trans trauma, but one of them is really important here: Slivers. If you haven’t, there’s an important piece that you need to understand, and it’s this: growing up trans in the West is inherently traumatic. Our entire culture is very, very good at telling us how wrong, how monstrous, we are for the cardinal sin of being born trans. Many of us—most of us, of a certain generation—grew up in homes where if our transness were ever discovered, the results would be catastrophic at best and fatal at worst.

This reality sparks the fight/flight/freeze/fawn response, an evolutionary response built to save your life when you’re in life-or-death situations. At a basic level, most of us grew up in a home where, instead of sharing it with a kind and loving family, the evolutionary equivalent of a hungry tiger prowled our hallways. Small and alone and afraid, there was no way we could fight back and win, no chance of flight. Only by fawning—by magnifying the desires of those dangerous or perceived-to-be-dangerous family members and minimizing our own needs, could we appease these people.

And survive.

And if that sounds a lot like the masking we talked about a moment ago, you’d be absolutely right. Fawning for an extended period of time is masking, and we each had to craft a mask of our own pain and suffering, the rictus grin of false happiness pasted haphazardly on it, sharp and savage teeth digging into our own lips as we tried to reflect the face of our fear back upon it.

Only then would the tiger in our homes prowl on, satisfied for now that we were like them, a fellow tiger.

But that tiger never stopped hunting, did it?

Which means we had to mask perfectly for them. They only had to notice our true selves once. But us? We had to successfully hide that self.

Every.

Single.

Time.

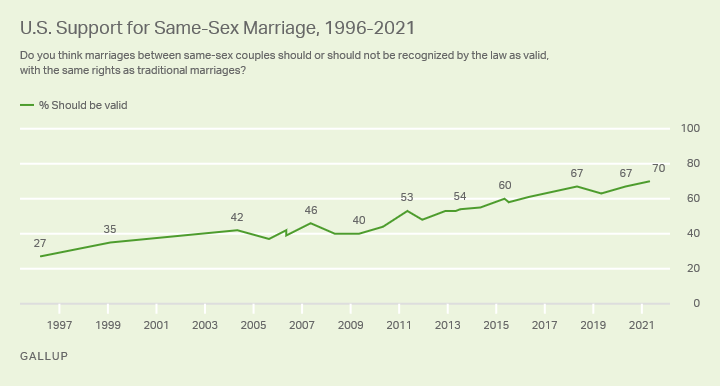

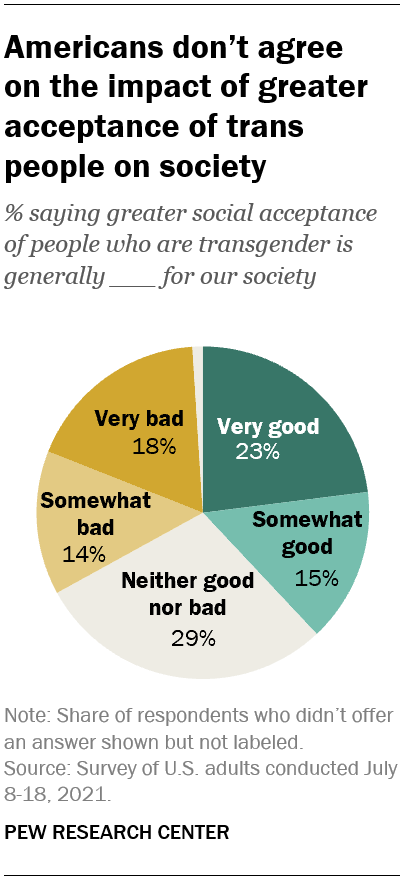

It’s so easy to forget that widespread acceptance of queerness is so, so recent.

And that widespread acceptance for transness lags far, far behind.

Even for those of us whose families turned out to be loving and supportive of who we are…

How is a small child supposed to tell the difference between a large housecat and a tiger in the dark?

So we wore the mask until we came to believe it was our face.

Unmasking transness

Escaping trans imposter syndrome really depends on two things, because of this trauma we share:

Letting go of the perfectionism that grips us.

Unmasking, and showing our authentic self to the world.

If you’ve read anything I’ve written, you’ve probably noticed by now that I’ve been on a bit of a personal mission to tear down the internalized supremacy culture I, like most folks in America, have going on in the dark corners of my head. It’s not easy, and it’s a hell of a process. It’s a good thing, and work I can enthusiastically recommend… but it’s not quick. And it’s not easy.

Unmasking is an idea that’s come out of neurodivergence research, and specifically from autism advocacy, where it has been by far best studied, and members of the trans community can take a few lessons from the work our neurodivergent siblings have done.

Autistic folks, like trans folks, grow up learning to hide many of the essential parts of themselves in order to avoid abuse by their allistic peers and family members. Like trans folks, autistic folks craft socially-acceptable masks to hide themselves, and like trans folks, autistic folks are actively harmed by maintaining those masks. Unmasking, then, is the process where they work to honor their sensory, physical, and social/emotional needs, like stimming in public when they need to, engaging in or disengaging from social interactions, embracing their special interests—in a nutshell, they work to live authentically, regardless of the judgement of allistic people around them.

Sounds so simple, doesn’t it? Well, like unlearning supremacy culture, it’s easier said than done.

At its heart, imposter syndrome is something called a cognitive distortion, which is just a fancy way of saying “a misperception that harms us.” That imposter syndrome you feel or have felt, the sense of not being as trans as the other people around you—it’s fundamentally not real. It’s the self-image equivalent of an optical illusion, a trick your mind plays on you in order to try and better understand a world that doesn’t quite make sense.

We know that the best ways in general to beat imposter syndrome are:

Understanding why and how it happens.

Deep, personal, human connection.

Yes, this means sharing the parts of yourself that you’re ashamed of. In fact, the more ashamed you are of them, the more important it is to share them.

Yes, your failures too.

Honestly? Your failures especially.

Forgiving yourself.

Letting go of your perfectionism.

And what it means is that the cure for trans imposter syndrome is, for better or worse, trans community. Mask off, tender, terrified, beautifully, wonderfully true face for everyone to see, maybe for the first time in your whole life.

Authenticity.

And that's going to mean sharing parts of yourself you never imagined you'd let anyone else in the whole world see. God knows I've shared things about myself, just here on this Substack, that I never imagined telling someone outside of a therapy office. It's terrifying, when you've been masking your whole life, to let it slip deliberately.

But ohhhhh, it's so incredibly healing to whisper your truth aloud for the first time, to be met with a chorus of “Me too!”s.

I don't know if you need to hear this. I don't know if it means a whit to you. But, on the off chance that it is something you need to hear:

Whether you're a basic binary gal, just a little bit nonbinary, a guy who never wants to give up his breasts and the dresses you love, or any other type of the wonderful spread of transness and nonbinary identities, no matter what you might or might not want for your body:

Yes, you belong. And yes, you're every iota as trans as the rest of us.

my autistic unmasking led to my gender unmascing. once i got to the place where i could comfortably say 'i am autistic', it was only a matter of months that my gender was freely accessible to me.

The relatively recent experience of spending a lot of time with LGBT people at an educators' conference (written about on my own SubStack) was profoundly beneficial because so many of them (especially those in their 20s) weren't masking nearly as much as anyone my age (over 40), and I was able to see that what people had often told me was ASC (in me) was far more likely to be untreated CPTSD.

I'm still seeking treatment but it's been an immense relief to be able to be so candid about this with other trans people who have been figuring out their own coping strategies, doing their own research, and getting their own treatment.

On a separate note, Doc, only days after I commented on one of your pieces that I'd had a particularly bad coming out to my colleagues (bearing out the value of your advice), I did manage to have something of a reset by posting on a Staff bulletin board my new e-mail address (that week), as well as my pronouns and full name which hadn't been disseminated as clearly, months before. It was the start of Trans History Week so I posted a few suggestions for how we could integrate it into our lessons, and the result was, as one colleague, "...the most hearted message in living memory."

Thanks, again, for all you do here : )