So, you think you might, maybe, possibly be trans, huh?

Yeah. Yeah, that’s scary as hell, isn’t it?

When I was questioning, I told my wife that it felt like I was hurtling through space in a spacesuit with no visor, tumbling and completely out of control. No sense of up or down, left or right, no way to know where I was going, just a sense of incredible momentum.

I want to offer you a little help here. Maybe you’ve looked through some other guides to questioning your gender, and things just haven’t felt like a good fit to you… and yet, this question just won’t go away. That’s okay. I’m going to try to strip all the interfering stuff away, and keep things as simple as humanly possible. I’m also going to provide sources for everything I can, so you know it’s not just me saying things.

And hang in there. It’s going to be all right. You’re not going to be alone.

I promise.

How do you question your gender productively?

Many, many, many people get stuck in a rut questioning their gender for months or years, unable to come to an answer. Unfortunately, that happens because a lot of ways of questioning your gender don’t get at the heart of what it means to be trans, only some of the symbolic and stereotypical stuff.

Why? Because gender is weird and complicated. And that’s okay! But gender is everywhere, all around us, and that means there’s a lot of background noise that gets in the way. Most questioning strategies don’t really deal with any of that noise, so it muddies up the answers you get. They tell you to go put on a skirt and ask if you like it, or something like it. Not so helpful if you’ve been a crossdresser for years, is it?

To question your gender productively, you need to be systematic, and you need to clear out as much of that background noise as you can.

One last thing before we get to questioning

This one’s going to be hard. Are you ready?

Right now, you need to accept—really accept, in your heart—the possibility that you could be transgender.

Anyone could be. It’s frankly pretty common. You’re no different, in this respect, from any other random person on the street that you might run into. Any one of them could be trans. Some of them are. I mean, roll a 20-sided die every time you see someone new. Every time a 20 comes up, that’s a trans person, statistically speaking.

Okay. What’s the question?

The second spot people get hung up is that they try things, and those things don’t feel right to them. Say, someone who’s wondering if they might be a trans woman tries on a frilly, pink dress, looks in the mirror, and is disappointed. Does that mean they’re not trans? No. It probably just means they don’t like that particular dress. It could be because they’re not trans. It could also be because they’re a trans tomboy, and would much rather be kicking ass in Doc Martens and biker leathers than a dress of any kind. And yes, there are trans guys who love feminine clothes and makeup and all that jazz too.

It’s all just stuff. It doesn’t mean anything.

Author’s note: This section used to include a note about F1nn5ter as an example of a “femboy, cis man,” to quote the original content, who was confident in his gender but enjoyed presenting as a woman. On March 1, 2024, he came out as genderfluid, so that section has been removed.

So here’s the question that you need to answer:

Do you want to be the gender people thought you were when you were born?

Being trans means a person has something called gender incongruence, which is a medical way of saying that they want to be a gender that isn’t their gender assigned at birth. If you’re paying attention, that’s exactly the question I wrote just above. And we need to look for desire—what you want—because wanting to be a gender is what it actually means to be that gender. There’s no difference. They’re the same thing.

But… it’s not really helpful by itself, is it? Like, I knew that question, and it still took me over 35 years to start questioning my gender.

Why do we care about desire?

Remember Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs? Looks a little something like this:

Needs are things that we require for our survival, so if it’s a thing on Maslow’s hierarchy, we generally need it to live. There are a few things that vary from person to person—reproduction, for instance, is essential for some of us and absolutely not for others—but these things are the hard requirements for life for the average person.

What you’ve probably learned about Maslow’s Hierarchy is that you can’t deal with stuff higher on the pyramid until you deal with stuff lower on the pyramid. Like, if you don’t have food or water, it doesn’t especially matter to you if you’re at risk for a heart attack. That understanding is correct, but it misses one really important asterisk: the needs higher up on the pyramid don’t just go away because you’re dealing with lower-order needs. They’re still there, eating away at you. Mostly, they’re causing stress to build up.

Stress isn’t just a feeling. Really, no feeling is “just a feeling”—they’re chemical, physiological reactions in your body—but stress in particular comes from the buildup of cortisol and some other chemicals in the tissues of your body. That’s good in a world of fight or flight, because it gets you ready to do those things, but unless the stress can be relieved it can very literally kill you. Stress needs to be flushed out by meeting those needs. And not doing so? It takes almost three years off of your lifespan, making it about 50% as bad for you as smoking, which is the worst possible thing you can do to shorten your lifespan.

So, yeah. It’s really bad. This is why hardworking people just drop dead of stress at fifty or sixty.

Desire is really important here because desire is how our body tells us that we’re not meeting a need. Think about the last time you were thirsty—you had an unmet need for water. You desired water. And if you didn’t get some, the desire just got stronger and stronger until you had to do something about it. Desire that doesn’t go away, in other words, is how our body tells us that we have a need that we’re not meeting.

You’re probably wondering right about now how all this relates to you maybe being trans, right? Well, check out the middle level of the pyramid—love and belonging. All of those specific needs fall under the umbrella of ‘authentic living,’ because living honestly and openly as yourself is the first, most important step to having deep friendships, intimate relationships, and stuff like that. You really can’t have those things if you’re living a lie, can you? Which means that a trans person who’s living in the closet, whether they know they’re living in the closet or not, can’t meet these needs. That’s why the question we talked about earlier—whether you want to be the gender people thought you were when you were born—is important. Cisgender people want to be their gender. They have a need, and it’s met.

This is why trans people come out, whether we transition or not. It’s not us trying to be special or brave or what have you. It’s us trying to meet the needs we need to meet in order to survive.

And if you’ve got this question, this desire, that just won’t go away? It might be you just trying to survive too.

Let’s science the shit out of this!

The cool thing about all this is that if feelings and needs are real, physical, chemical reactions in your body, that all of this is science. Science is cool!

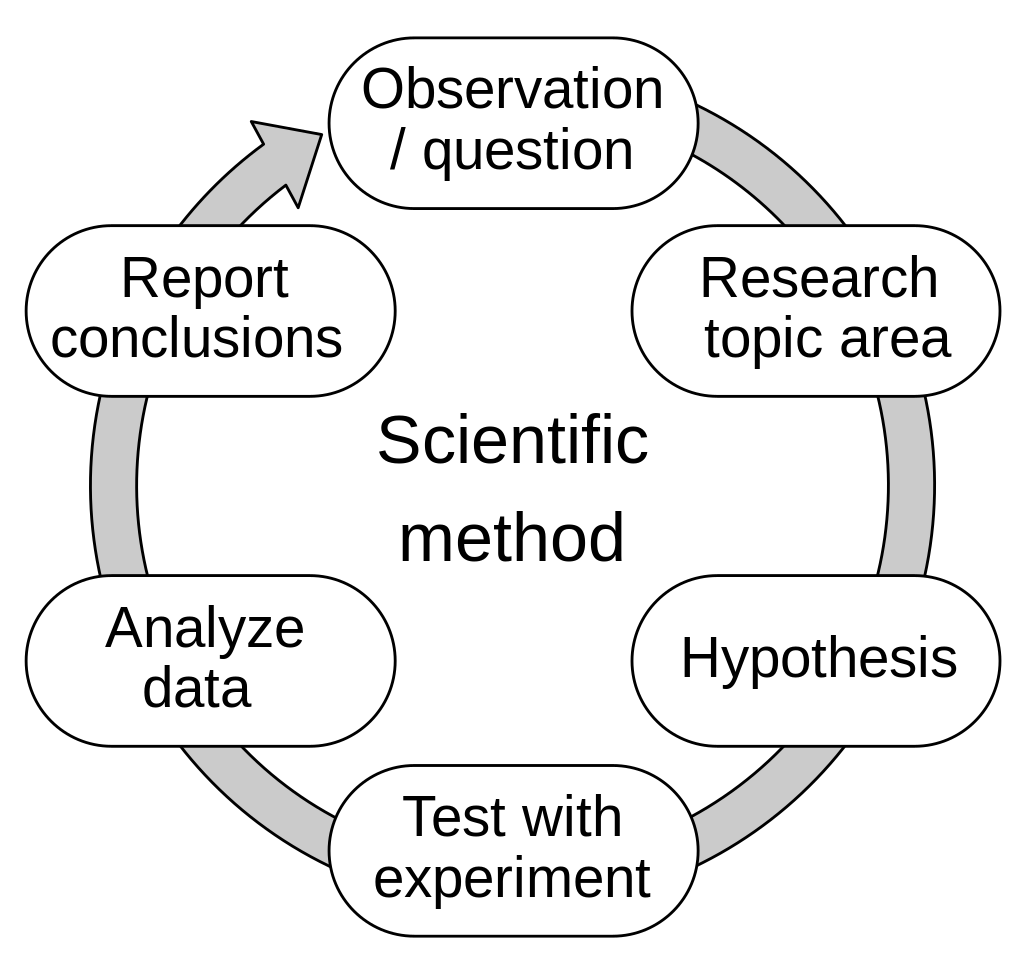

The cool thing about the question we’re trying to answer—whether or not you want to be the gender people thought you were when you were born—is that it’s an investigative question, which just means that it’s a testable, specific question with possible answers that don’t overlap. That means we’re already in the middle of the scientific method. So, that means that we can just follow the method through to find an answer.

We have our question. Let’s research the topic area and define our terms!

Defining our terms

A lot of people get hung up in questioning their gender right here, because there are a near-infinite number of possible genders out there, from binary to nonbinary genders, and even within binary gender there’s a whole lot of possible variations. There’s so many options! How can you know which one you want to be, right?

This is where well-defined terms are really helpful.

Being cisgender means that your gender matches the gender you were assigned when you were born.

Being transgender means that your gender does not match the gender you were assigned when you were born.

The word “match” is really important here. It means equal to, corresponding to—in other words, a perfect fit. So, anyone is cisgender if they’re a 1:1 match to their gender assigned at birth, and anyone is transgender if that’s not the case.

Most people and most guides to questioning your gender get hung up trying to prove to the reader that their gender is this or that trans or nonbinary identity, but science doesn’t work that way, and that’s why so many people can’t make any progress that way. Science can’t prove that a thing is. It can only prove that a thing isn’t, or it can fail to do so. That’s called falsifiability—the ability to disprove a scientific hypothesis.

So, at this point, you’re probably thinking, “but I can’t disprove that I’m any of the almost-infinite varieties of transgender and nonbinary genders out there! There’s too many!”

And you’re right. You can’t.

But whether or not you’re cisgender is falsifiable. That’s just one gender.

Hypothetically speaking

What we’ve just built here, as part of our research, is the backbone of what’s called a hypothesis. A hypothesis is just a testable, falsifiable assumption about something you’ve observed in the world—in this case, that you might be trans—and which you will attempt to disprove. If you are able to disprove it, then you know the hypothesis was untrue. If you can’t, then the hypothesis holds. And, since we can only falsify a hypothesis—we can’t disprove a negative (in this case, that you’re not cisgender)—the hypothesis we need to test is pretty easy to build:

Hypothesis: You, the reader, are cisgender.

That means that we need to try our best, systematically to show that that hypothesis isn’t true. Because—and again, this is why you needed to accept earlier that you might be trans—the hypothesis that you’re cis and the hypothesis that you’re trans are inherently equal. Neither one is the default. And, if you’re interested, there’s a very, very good essay about this exact thing that you might want to read, either now or later.

We’re not trying to disprove that you’re cis because that’s some kind of standard. We’re doing it because there’s just one thing to disprove.

Because, if your gender isn’t a 1:1 match to your gender assigned at birth, you’re transgender. What your gender is, at that point, is a question for another experiment, but no matter what, if we can falsify that hypothesis, you’re trans.

Designing a gender experiment

The last area where people get stuck when questioning their gender is in experimentation. The typical advice for experimenting amounts to “go put on some clothes and see how you feel,” which is kind of not really helpful because, again, it’s just stuff. Doesn’t mean anything. And even if it did, “see how you feel” is kind of hopelessly vague, isn’t it?

Any experiment needs controls and variables. Basically, controls are things that are consistent, fixed, and unchanging, so they’re stuff that doesn’t interfere with the results of your experiment. Controls are good because they reduce the number of things you have to think about when you’re looking for results.

Variables? That’s what we’re measuring to find our answers. In this case, we’re going to be measuring your desire—what you want and why—and that has a very important impact on our controls.

When we’re measuring feelings, we’re doing something called qualitative research. You’re probably more familiar with quantitative research, which is all about numbers and values. It’s super useful, but qualitative research is very frequently used as a first form of research, before researchers can perform quantitative research, because qualitative research is really good at figuring out what’s there, as far as peoples’ feelings and perceptions are concerned.

Remember, this is science. We want to keep things focused and simple in each experiment. We can always come back later and do quantitative research to figure out how strong your feelings are once we know what they are.

The variable

We’re measuring feelings with this experiment. What it means to be trans is that you want to be a gender that isn’t your gender assigned at birth. In turn, that means that whether you’re trans or not is a dependent variable—in other words, what it is depends on an independent variable. The independent variable is what we need to test for.

That independent variable is what you desire.

That means that our experiment needs to test for desire.

When we test for desire, we need to know two things:

What you desire—and it can be multiple, conflicting things.

Why you desire it—the source of the desire

We care about what you want for pretty obvious reasons—if you were assigned male at birth (AMAB) and want to be a girl, that’s a big ol’ clue. We care about why, however, for equally important reasons. Let’s say that you’re AMAB and you desperately don’t want to be trans… because you’re afraid that your parents will be upset if you are. Thing is, that doesn’t actually answer the question, because whether your parents approve of you being trans or not has nothing whatsoever to do with whether you are trans or not. In an experiment, we call that a false negative.

A false negative (or, oppositely, a false positive!) wouldn’t mean that you are or are not trans, just that the test got corrupted and the data’s no good either way. After all, a cis person could (and probably would!) desperately want to be not trans for the exact same reasons a trans person might wish the exact same thing.

Asking why to your what in qualitative research will tell you if the test result is telling you something useful.

Controls

Since we’re measuring feelings here, and since there are lots of feelings out there, we’re going to get interference from feelings we’re not testing. We talked about one example of how fear can mess up test results a moment ago, but there’s a whole lot of other stuff that will give us bad results. If one or more of those things show up when you’re asking yourself why you’re feeling something, the data isn’t useful, and needs to be set aside.

To control for those interfering feelings, here’s what you need to ignore while you question your gender. They’re what are known as our exclusion criteria:

Fear. Being transgender is neither good nor bad, just like being cisgender is neither good nor bad. Being afraid of being trans is being afraid of the consequences if you are. None of that matters if you aren’t, so it’s nothing but interference when you’re trying to get to a simple, yes-or-no answer as to whether you’re trans or not.

Your feelings about what’s possible with transition, or how hard it is. It’s the same as with fear, in that none of this matters unless you are, but with the added (and incredibly important) part that not all trans people transition.

Your obligations to your family, especially your partner. Just like with fear, this doesn’t and can’t matter until you have an answer to whether you’re trans or not. Besides, there’s a lot of good evidence that being trans is at least partially genetic, so if there’s one trans person in a family, there’s a really good chance that there’s another. Especially if you have kids.

Your employment or living situation. Again, none of this matters until you have an answer.

How you feel about stuff, be it dresses or jewelry or makeup or sports or cars or anything else that’s usually assigned “boy” or “girl.” We talked about this earlier with F1NN5TER—stuff doesn’t matter, in and of itself. There are a million ways to be any given gender.

Your feelings about sex and kink. Yeah, that seemed to come out of nowhere, didn’t it? Don’t worry, we’ll circle back around at the end. The short version is that these don’t matter one way or the other either, and we’ll talk about why a little later on.

Lust or envy. Envy can point really strongly toward a trans identity, but a lot of trans people say that they had a really hard time telling the difference between lust—which has nothing to do with anything—and envy—which does—before they realized they were trans. Since it’s often hard for people to tell the two apart, it’s better to ignore them both.

Just as importantly, there are a few emotions that we want to designate as our inclusion criteria. If a result meets an inclusion criteria, that means it’s pretty much automatically useful data. Here are our inclusion criteria:

When there’s no obvious reason why you feel the way you feel. If you want something for completely inexplicable reasons, that means it’s an expression of pure desire, and pure desire is exactly what we’re measuring!

Hope or longing. Hope is an expression of desire, just placed into the future. Longing is the same thing as hope—it’s just something we don’t believe we can have. Either way, they are expressions of pure desire, which is what we want to measure.

Regret. Regret is desire for something that didn’t happen. If you regret something, it means you wanted, and still want, something different.

Despair. Despair is desire for something we think is flatly impossible. If we feel despair over the belief that a thing is impossible, it means that we do desire it.

So, if we check the causes of our feelings and find an item in our exclusion criteria, we ignore it. If we check them and find one from our inclusion criteria, that’s a valid, useful result.

The test itself

Go grab a pen and paper, or open a word processing program, so you can take notes.

So that we can have consistent, controlled-for results, I’m going to present you with three scenarios. I want you to imagine yourself in these scenarios. At the end of each scenario, I’m going to ask you a question. Jot down your immediate, emotional, gut-level answer to it, and then jot down why you feel how you feel, to the best of your ability. You can absolutely have multiple answers for each scenario, if you feel multiple things at once.

Once you’re done with all three scenarios, go check what you wrote against the list of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Cross out any answers that mention an exclusion criteria, and circle or highlight any that mention an inclusion criteria.

Afterwards, we’ll talk about understanding the results.

Test time!

Scenario 1

Scenario 1 has two versions, depending on whether you were assigned male or female at birth.

Scenario 1—If you were assigned female at birth

You wake up tomorrow morning and you have the body of a typical guy. You check your ID, and it has a masculine name on it, and it says your gender is M. You closet is filled with a variety of guy’s clothes. You get dressed and head out.

You meet some friends, and they act like you’ve always been this way. You chat about some shared history, and they talk about a fishing trip you went on together in the past, as though that’s the way it’s always been. You hang out, play a little ball for fun, and then part ways.

On your way home, you swing by the grocery store to buy some milk and bread, because you’re running low. As you’re in the checkout line, a guy behind you sees that you’re wearing a jacket for the local sports team and asks if you saw the last game. You didn’t, and and he tells you about a play he things was particularly great. You buy your groceries and head home. Nobody bothers you or hassles you as you do.

When you get home, you find a small box with your feminine name on it. Inside is a note and a small, red button. The note reads:

Push this button to return to the universe where you have a feminine body.

The button’s not going anywhere. You can press it any time you choose, or not press it at all. There’s no hurry to make a choice, but if you press it, it’s a one-way ticket back to your original reality.

What do you do, and why?

Scenario 1—If you were assigned male at birth

You wake up tomorrow morning and you have the body of a typical woman. You check your ID, and it has a feminine name on it, and it says your gender is F. You closet is filled with a variety of women’s clothes. You get dressed and head out.

You meet some friends, and they act like you’ve always been this way. You chat about some shared history, and they talk about a mutual friend’s recent roller derby game, as though that’s the way it’s always been. You hang out, gab for a while, and then hug and part ways.

On your way home, you swing by the grocery store to buy some milk and bread, because you’re running low. The lady running the checkout compliments your skirt, and you cheerfully tell her it has pockets. The two of you talk for a little bit about where you got it, and she wishes you well as you take your groceries and head home.

When you get home, you find a small box with your masculine name on it. Inside is a note and a small, red button. The note reads:

Push this button to return to the universe where you have a masculine body.

The button’s not going anywhere. You can press it any time you choose, or not press it at all. There’s no hurry to make a choice, but if you press it, it’s a one-way ticket back to your original reality.

What do you do, and why?

Scenario 2

Scenario 2 has two versions, depending on whether you were assigned male or female at birth. Each should be repeated three times, once with each body type described in the bullet points.

Scenario 2—If you were assigned female at birth

A magical fairy flies in through your window. She waves her magic wand and poof! You’ve suddenly got

a traditionally masculine body, with narrow hips, broad shoulders, and facial hair

an androgynous body, with no features that look particularly masculine or feminine

a body with a mix of features which are strongly masculine and feminine—maybe breasts and a beard, or curvy hips and a chiseled, flat chest, or any other combination you can imagine

“Oopsie doodle!” the magical fairy says. “You’re not my fairy godchild! I’m so sorry! Would you like me to change you back? Do please hurry, because I’ve got to be going!”

You’ve never seen a fairy before, so you’ll probably never see her again once she leaves. What do you tell her, and why?

Scenario 2—If you were assigned male at birth

A magical fairy flies in through your window. She waves her magic wand and poof! You’ve suddenly got

a traditionally feminine body, with breasts, curvy hips, and no facial hair

an androgynous body, with no features that look particularly masculine or feminine

a body with a mix of features which are strongly masculine and feminine—maybe breasts and a beard, or curvy hips and a chiseled, flat chest, or any other combination you can imagine

“Oopsie doodle!” the magical fairy says. “You’re not my fairy godchild! I’m so sorry! Would you like me to change you back? Do please hurry, because I’ve got to be going!”

You’ve never seen a fairy before, so you’ll probably never see her again once she leaves. What do you tell her, and why?

Scenario 3

You’re ninety-two and a half years old and are sitting on the front porch of your home in a rocking chair, cozily nestled underneath a warm blanket. Your partner passed away last year, peacefully, in their sleep. Your kids, if you have any, are all well off, living their own lives, with their kids. You wish they called more often than they do.

You’re watching the sun set and reflecting over the life you’ve lived. You got the job you were supposed to get, lived the life you were supposed to live. You never did anything about the feelings you always had about your gender, and those feelings, those questions never went away.

How does it make you feel that you felt this way your whole life but never did anything about it, and why?

Understanding your results

Check your answers. If all of your answers got crossed out because of exclusion criteria, try the scenarios again, paying attention to other feelings you feel when you go through them, or design your own scenarios along these lines. If you circled any answers because they met inclusion criteria, focus on them first, and then on any answers that were neither circled nor crossed out.

I’m going to present the meaning of each scenario behind a hyperlinked button. The idea behind this is that, if you need to repeat a scenario, you won’t be at risk for reading the meaning before you redo it, and so that you can focus on each answer one at a time.

One last thing: ONLY YOU CAN KNOW YOUR GENDER. These experiments are meant to give you data so that you can sort through what you want, and why, but only you can know the truth of your heart. There’s no such thing as a definitive answer to any test for gender. Besides, If I, or anyone else, told you that you were, for sure, either cis or trans… would you believe me? Like any other question of identity, your answers need to come from inside you.

Before you click on any result, though, there’s one extra button. Only click on it if you’re hoping, right now, that your response to one or more of the scenarios means that you’re transgender, and that the reason why isn’t one of the exclusion criteria.

When you’re ready, click the meaning of the scenario you want to understand a little better.

Post-test questions

Why three scenarios when they get at the same sorts of things?

Simply put? Because people respond differently, in emotional terms, to different situations. Some folks who are really caught up in the churning of the present day, for instance, might be able to see what they want more clearly in hindsight.

Why do so many of the answers amount to “you’re probably some version of trans?”

Frankly? If you got far enough questioning your gender that you went looking for at least one, and maybe several, guides on how to do it and get an answer, you’re probably trans. The fact that you opened this article at all is, by itself, a pretty important sign that there’s probably something there.

Cis people don’t question their gender like that. For them, it’s kind of the same way you’d imagine what it might be like to be a lamppost: fleeting, and with rapidly-increasing horror if you were forced to really dwell on it.

Why can’t anyone just tell me whether I’m trans or not?

Because nobody in the world knows you better than you do.

What if I’m not sure?

That’s normal. Pretty much none of us are 100% sure, because the only way to have that much confidence is to be told when you’re little by someone you trust with all your heart. As soon as you realize—really accept—that a person’s gender assigned at birth doesn’t have to be their gender, you’ll never be 100% certain again, whether you’re trans or cis.

And that’s okay.

Why don’t you talk about gender dysphoria as part of questioning?

It gives both false positives and false negatives. Not all trans people experience gender dysphoria, but more importantly, cisgender people can feel gender dysphoria too. When cisgender women has their breasts removed as part of breast cancer treatment, for instance, they often feel dysphoria at the absence of their breasts, which can only be alleviated by reconstructive breast augmentation.

This is what’s called a confounder, or an independent variable that we’re not measuring. Confounders can really mess with good data, so we have to exclude them from any well-designed experiment.

Wait, why did you exclude anything to do with sex or kink?

That’s a really big question—and probably a whole article by itself, if I wanted to answer it completely. The shorter version is that sex and kink are confounders, just like dysphoria is.

You’ve heard of Rule 34, right? Anyone can develop a kink about anything, and one part of anything is fantasizing about being another gender. Gender play (don’t google that term if you’re at work or around kids!) is really common. And since anyone includes everyone, that means some people with gender play kinks will be trans. And that’s normal. Healthy, really, just like any consensual kink.

Some people have gender play kinks. Some people are trans. Some people are both trans and have gender play kinks. That means that a gender-y kink can definitely be a sign of a trans identity… or it can mean absolutely nothing. It’s something that each person has to figure out for themselves, and that has to come after they have an answer they know whether they’re trans or cis.

…what if I think I’m trans, after this experiment?

If you tell me you’re trans, I will believe you.

You will be welcome in our spaces, and if you have questions that you need help finding answers to, or just want to talk to someone about it who’s been there, please do reach out.

You are the one and only expert on who you are.

I believe you.

Resources for further reading:

Love Lives Here: A Story of Thriving in a Transgender Family

It’s Just a Fetish, Right? Maybe. Or Maybe it’s Gneder Dysphoria

Acknowledgements: It’s like to thank the following people for their feedback in developing this article: Terra “That one unhinged bitch with the too-small tits” (she insisted that she be addressed in this way), Ellie, Emily, Tattie, Slenderwoman, Faith, Tammy, and Emily.

Another wonderful article and so thorough. This helped me identify that the exclusionary variables are the only thing holding me back. I have been looking for a local therapist and think I may have finally located one. I really want the first visit in person. I do not know where it will lead, but I know I need it. Thanks for doing what you do. It really is a big help!

I know its so sappy but when I went to the 'I hope I'm trans' button and saw the message I made the biggest smile I've made for a long time, and it comes back every time I look back at it.

I've saved both a photo of myself and of the screen to look back on and remember this moment. Thank you so much for doing what you do, this has made me feel amazing and really affirmed me. And thank you for commenting on someones reddit post that led me straight here!