Can I Offer You An Egg In This Trying Time?

On the memetic rhetoric of transgender coming-out comics

On July 17th, 2020, at 10:10 PM–Eastern Standard Time, mind you–a transgender friend of mine sent me a link to a webcomic, saying that it felt very relatable to her. So, since I wanted to be a good friend and try to understand her situation a little bit better, I read it… and immediately plunged into an eleven-day-long panic attack. This comic said things to me openly that I’d never said to anyone, ever. I was rung like a struck bell. And, at the end of those eleven days, when I said to my therapist, “Melissa, I don’t think I’m cis,” her response was a simple, gentle, “I don’t think you are either.”

I had never suspected I might be transgender. I had never once crossdressed. Never once knowingly wished I was a woman. And yet, here I stand before you all, trans as hell and proud of it.

I am part of what we are now beginning to recognize to be a demographic tidal wave that will, in the next five to ten years, reshape higher education as we know it. Transgender people, and especially transgender youth, are recognizing and actualizing our identities at absolutely unprecedented rates, catalyzed by a perfect storm of quarantine isolation, social media communication, and new ways of describing the trans experience. This talk sets out to examine one of these new modes and how it functions, both to foster community through shared experience, and to provide trans people who haven’t yet realized their identities with the vocabulary and the tools to effectively question their gender. As you might imagine from the session title, I am speaking, of course, of the transgender coming-out comic.

Terminology

We need to do a little legwork before diving into these comics, since there are very often major misconceptions about what it means to be trans. I’m going to start with some terminology, because the community uses a fair bit of slang which often appears in these comics, and which won’t make much of any sense without explanation.

First of all, trans people can generally be split into two groups: binary people–men, or women, that is–and nonbinary people–folks who are neither, both, or some other kind of gender altogether. Many cis people imagine there’s a sort of hierarchy here, where a binary trans person is somehow considered to be ‘more trans’ than nonbinary people. However, and I need to be absolutely clear here, there is no such thing. Each trans person is exactly as trans as any other trans person.

Because of this, the community has moved away from terms you may be familiar with, like MtF or FtM, that is, male-to-female or the inverse, which privilege binary trans identities, and also from AMAB or AFAB–a male assigned at birth or a female assigned at birth–which focus heavily on the birth gender of a trans person and which is made largely irrelevant by their transition. Generally, the community uses ‘transmasculine,’ or someone who is moving towards somewhere generally in less-feminine and/or more-masculine spaces, or ‘transfeminine,’ which would be someone who is moving towards somewhere more feminine and/or less masculine. We continue to use an initialism I’ll be using a fair bit in this presentation–‘AGAB,’--which is the generic, “a gender assigned at birth.” It is mostly used as a gender-neutral term in the definitions of other things, and is a holdover because a better option hasn’t yet been found..

Finally, a bit of slang: an egg, which you’ll hear a fair bit today and which the title of this presentation references, is a term for a trans person who has not yet realized that they’re trans. Hatching, then, is slang for the often-sudden realization that a person is trans. It’s particularly apt, because once you have this realization, you can never really go back. Also, because trans people tend to be punsters–Hormone Replacement Therapy has many affectionate nicknames, from anti-boy-otics to boy sauce to titty skittles–there’s a pretty reasonable chance that when a person hatches, you wind up with a chick.

The last bits you’ll need to know are the polite euphemisms the trans community uses to talk about surgeries we sometimes get: top surgery can refer either to breast augmentation for transfeminine people or the removal of breasts for transmasculine people. Bottom surgery, which this presentation will not address and which is included here only for terminological completeness, refers to any of over a dozen surgical procedures which can be performed on the genitals.

Lockdown

Before we get to the comics themselves, let’s talk about demographics and the COVID lockdown of 2020. Historically, the transgender population has been estimated at around 0.6% of the total population of the US. These numbers had been shifting a little over time, mostly as members of Gen Z increasingly came out as one variety of queer or another. You’ve probably heard about how queer Gen Z is elsewhere, but let’s quantify things a bit. In 2017, one of the last big surveys of the trans youth population by the CDC found that about 1.7% of Gen Z self-identified as transgender which, given that it was almost triple the known, overall US rate, caused a bit of a stir. During the COVID crisis, however, these studies continued–and some surprising numbers began to emerge. The first of these, a study that came out in the summer of 2020 and which included in a significant part of its corpus the first big lockdown event, found that 2.2% of all 10-20-year-olds self-identified as trans. In the spring of 2021, a study of over 3,000 9th-to-12th-graders–the first major population study which began its data collection after lockdowns began–found that 9.2% of those students were trans, when provided with a little bit of vocabulary. While that study is still an outlier, the headcount of trans youth continues to rise, capped by an enormous, nearly-11,000 participant Pew Research population study that found that over 5% of all people under 30 are transgender, released last year.

Why this explosion, though? Psychology offers some answers. While there is a big cultural idea that trans people always knew we were trans, many–like myself–show that lie for what it is. In reality, there are several life stages where trans people typically realize they’re trans: in adolescence, yes, but also in our early adulthood, in our early-to-mid thirties, and when we retire. These life stages correspond with major turning points in life, when questions of identity are already up for grabs–the transition from childhood to adolescence, the transition to adulthood, the transition from the scarcity of young adulthood to sufficiency, and the transition from the working world to retirement. That being the case, it’s natural for other questions of identity to bubble to the surface at those points in time.

Additionally, there seems to be a pretty simple formula for having a gender crisis if you’re trans and don’t know it, or are in deep denial. A gender crisis happens when you feel a certain level of basic safety–good old Maslow popping up here–when you have a certain level of basic awareness of the existence of trans people and what it means to be trans and, finally, when at least one major coping mechanism is overwhelmed or removed. COVID lockdowns were a perfect combination of these factors–people felt safe at home from something terrifying in the wider world, those same lockdowns removed a lot of coping mechanisms from people, and pretty much everyone, trans or cis, dove deep into social media to pass the time. This caused, as Flaherty et al (2021) observed, a “deterioration of self” which caused people to go looking for things to identify with–and found a new wave of memetic communication about the trans experience cresting before them.

Comics & Visual Rhetoric

According to McCloud (1993) in “Understanding Comics,” comics at their best bring together both the written and visual medium to support each other’s strengths and create something that no other medium can do. When working together, text and picture can represent a scene while adding depth to what that scene means for its characters and readers. For example, a picture of someone staring at a mirror with a distraught look upon their face can convey that the person is not happy with how they look. However, we don’t get anything more than that. Add text, and the inner emotions behind that distraught look become clear and the scene becomes far more impactful.

Comics are incredibly helpful for transgender storytelling because the process of transition is both internal and external. Externally, there are obvious physical changes, but just as importantly is showing the emotions we’ve suppressed our whole lives. Internally, trans people have to wrestle with a wealth of emotions. The terror of realizing that you are trans. Depression and dysphoria from your body and your place in the world. Worry of what’ll happen when we decide to come out. Relief, at being accepted by our friends and family. The pure joy we feel when we finally recognize ourselves in the mirror. Comics effectively portray these things because, by combining text and picture in tandem, all of these things can be represented at once.

Take, for example, the opening page of Jadzia Axelrod’s 2022 graphic novel “Galaxy: The Prettiest Star” Here, the protagonist is getting ready for school. Normal. Happy, right?

Restore the inner monologue, and you see from the first panel, and catalyzing on panel five, her distress. Her. You see, in this comic, the protagonist is an alien princess trapped in the body of a human teenage boy. Galaxy’s inner monologue, which is given to us in textboxes, tells us why she’s feeling this way: she knows she is in the wrong body, but is helpless to do anything about it. This is a well-known feeling that many transgender people have. By combining the visual with the textual, both the representation of unhappiness and her gender dysphoria are brought together for the reader/viewer.

Here we have three panels from Robin Brooks’ comic “How It Actually Happened”, which focuses on her first steps exploring the idea that she may be transgender. These specific panels show Robin shaving her legs for the first time and realizing not only that it felt good, but that it was the first time she ever liked how her body felt. Without the text in these panels, this life-changing event would be completely inscrutable.

It’s not only the presence of text in a panel, but its absence, especially when the panels before and after have text, that can add weight to the story by highlighting an emotional beat that leaves a character speechless. This can be a powerful tool in transgender storytelling because the process of transition is filled with moments in which we are left truly speechless as we try to make sense of all of our conflicting and overwhelming emotions.

Returning to “Galaxy: The Prettiest Star”, we have a a two-page splash, in which Galaxy’s girlfriend Kat has dressed her up and done her makeup for the first time. Kat’s speech balloon on the left page is small and quiet, and the page with Galaxy looking at herself in the mirror is completely blank. Up to now, almost every panel in the comic has either had speech bubbles or inner monologue textboxes. Here, we are brought to a standstill with just an image of Galaxy looking at herself, utterly stunned. The nothingness tells us one thing: Galaxy is overwhelmed by the fact that the beautiful woman staring back at her is herself. By her face, for the very first time.

Similarly, Robin Brooks’ comic contains 19 panels, 17 of which either have speech bubbles or captions. The only two left silent panels clearly convey the emotions of the main characters. In the first, Robin and her partner, Jordan, are silent as they come to terms with the fact that Robin is trans. The silence of inner monologue and speech bubbles emphasize the impact of this realization. In the second textless panel, Jordan is hugging Robin, accepting her. The silence sells this moment and Robin’s overwhelming feelings towards this more than any text would do.

The Technical Communication Functions of Coming-Out Comics

One of the most fascinating aspects of trans coming-out comics is that almost none of them act as a simple announcement. Rather, they narrativize the artist’s journey to their identity–but are presented in such a way that they effectively become tutorial documents, as Yu describes (Yu, 2019, 226). Comics as a technical communication medium are particularly effective for transgender tutorialization, as the dialogic discourse which comics rely on–either with multiple characters on a page or between the artist and reader/viewer directly. These are not conversations between characters where the reader is a voyeur, separated from them, as is the case with film. Comics inherently and necessarily include the reader/viewer as a participant, because every frame needs to be actively stitched together into a narrative whole by that reader/viewer. Yu argues that this mechanism invites identification and engaged learning, so it follows that once a trans egg identifies with a character in a coming-out comic, it allows them to close a critical cognitive circuit: to think the thought, “I could be trans.”

And that’s critical, no matter how mundane it sounds, because there are as many unique ways to be trans as there are trans people. Anyone could be trans. Anyone. Any one of you could be trans. There’s no way of existing that would preclude a person from being trans, after all. The only requirement is that a person would simply prefer being a gender or genders that isn’t simply their AGAB. To illustrate this, I want to take a close look at what are probably the two most influential trans coming-out comics since the beginning of the pandemic. The first, Epiphany by Mae Dean, is a transfeminine perspective, and the second, The Weight of Them by Nate Stevenson, is transmasculine.

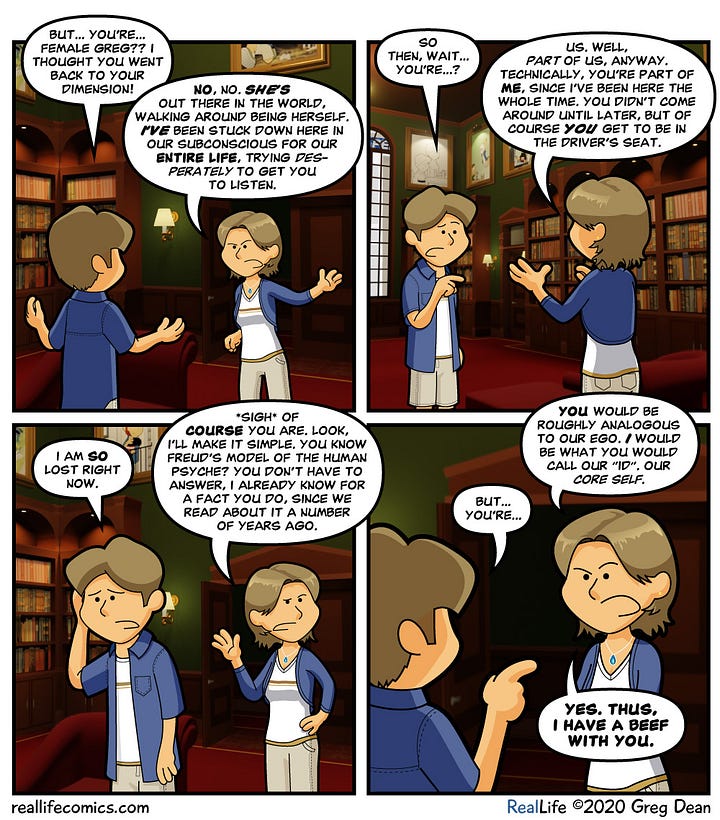

Mae Dean is the artist of the extraordinarily long-running semi-autobiographical webcomic Real Life Comics, of which Epiphany is a fifteen-page part. A well-known fixture of the turn-of-the-century webcomics scene, Mae had faded almost entirely from the public eye as the strip lapsed more and more as time went by, eventually entering a long hiatus in 2018–immediately, as it turns out, after she realized that she was trans. She made her gender public beginning in the summer of, 2020, and used Epiphany to tell her story. As a note, I have skipped a few pages in the interest of time.

The comic begins with a stark statement–a reproduction of the tweet which caused Mae to suddenly hatch in 2018. That tweet, by trans activist Kathryn Gibes, went very viral, to the extent that it is known simply as The Tweet in many parts of the online transfeminine community. It reads, “If you’re under the assumption that you’re a cis guy but have always dreamed of being a girl, and the only reason you haven’t transitioned is because you’ll be afraid you’ll be an ‘ugly’ girl: That’s dysphoria. You’re literally a trans girl already.”

Mae depicts the common initial panic reaction which accompanies a sudden hatching wordlessly, in the same way that Galaxy does. After this, she is immediately confronted by her id, her core self, who spends several pages being enraged that she has been buried for “three decades.”

The comic goes on to describe the “little thoughts in the back of [her] mind” which were that core self trying desperately to break through to Mae’s conscious self, telling us how she wished “on every birthday candle” that she could be a girl, how she wished for “shapeshifting” as a superpower–little example after little example of Mae’s gender trying to break through and be understood. And then, of course, Mae admits her fear and shame, that if she ever admitted to these feelings that people would hate her. These little examples, this visceral fear–they are overwhelmingly common, especially among transfeminine people who necessarily struggle against transmisogyny which, for those of you who haven't encountered the term before, is what you get when you cross misogyny with transphobia, and is often enforced with violence.. The combination, unfortunately, is far more toxic than the sum of its parts. To return to the comic, these nuggets of lived struggle offer the reader/viewer relatable experiences that they can latch on to as parallel with their own life, as Yu noted.

From this point, Mae disambiguates gender from sexuality. Mae is a lesbian, and many transfeminine eggs struggle with the separate axes of gender and sexuality, as the requirement that transfeminine people be exclusively attracted to men before they were allowed to access even gender-affirming therapy, let alone hormone replacement therapy or any other medical care, was not removed in America until 1994, and was not banned outright as a practice until almost two decades later. She then separates gender from performance–who we are versus who we look like and what we do–a second major problem in the transfeminine community, as until this requirement was set aside in 2013, a transfeminine person could be barred from hormones if she ever did not present sufficiently feminine at her therapist’s appointments. Turns out that that’s hard to accept for trans tomboys. This, as a note, is the source of the stereotype that trans women are hyperfeminine; until a little more than a decade ago, we were literally required to be in order to receive medical care of any kind. That expectation was not formally banned until last September, and is still widely practiced in many countries, and by some psychologists in America, regardless of the ban.

After this, Mae pivots to a discussion of coming out and transitioning, first considering strategies for telling her wife and her daughter. This too is a common pain point for transfeminine people, as until 1994, we were required to leave our families and cut all contact with anyone we had ever known before transition before we were allowed gender-affirming therapy. This is the source of the narrative that trans women leave their wives and families to pursue relationships with cis men, and it’s a common crisis point for many transfeminine people. Epiphany offers a model, here, of how a family can not only survive, but thrive in transition, as turns out to be the case in Mae’s real life.

Finally, Mae closes with the hardest part of the hatching process: self-acceptance, in that same emphatic silence we see used so often, and to such effect. The merging of the ego and the id. Discarding, once and for all, the mask, and the illusion that the masquerade can continue. What we see here is an emotional story, well-told–but also a very practical, nuts and bolts guide for how to question your gender, with answers for all of the biggest pinch points there are.

Nate “ND” Stevenson is one of the most famous transgender people working in Hollywood these days, but you probably don’t know his name. The creator, writer, and producer of the reboot of She-Ra and the Princesses of Power, Nate has an enormous list of credits to his name, including appearances on Critical Role, writing credits on over a dozen comics series and dozens of TV episodes across a large number of shows, a movie, and is the three-time winner of the Eisner award–and that abridges his list of achievements. I can promise: if you’ve seen drawn or animated media within the last decade, you’ve seen his work. Like me, Nate started to question his gender during the first COVID lockdown, and after a while, and a transformative surgery, he poked his first toe out of the closet with The Weight of Them, a beautiful comic about his top surgeries–and his journey into questioning his gender. As a note, one of the comics we’ll be looking at shows unsexualized, unclothed breasts, in the context of his transition. If, for whatever reason, this is a problem for you, I understand completely. Feel free to duck out for a couple of minutes; they come at the very start of this segment, and I won’t be lingering on those slides. Finally, I will be skipping over a few panels of this comic in the interests of time, in the same way I did with Epiphany.

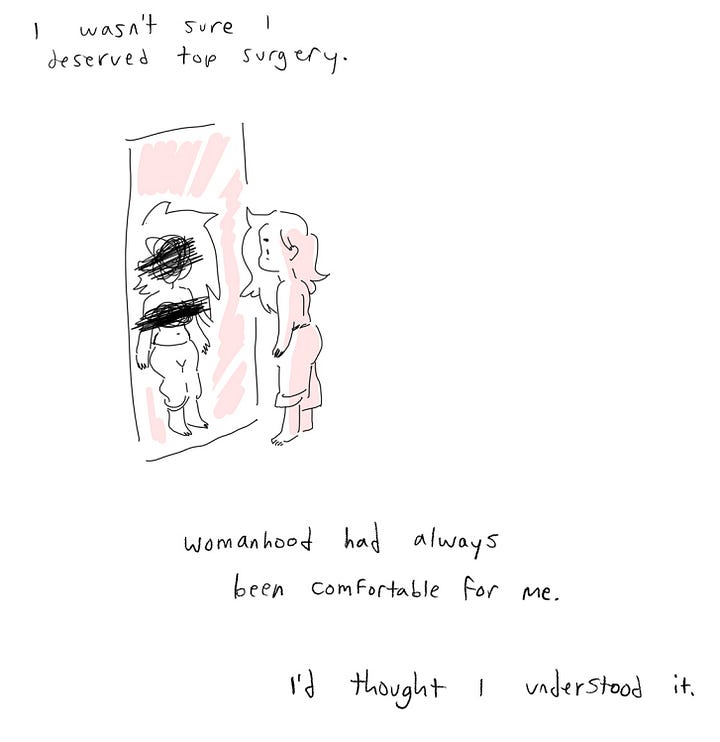

Nate begins in the first three panels here with a brief discussion of his first top surgery, a breast reduction. He moves through it quickly, focusing on how, immediately after, he knew the reduction wasn’t enough for him. He falls, on panel 3, into a deep depression in what is the first unambiguous depiction of dysphoria in this comic–and an existential depression that will not lift is one of the most common symptoms of gender dysphoria there is. He lingers here, never calling it out, but instead illustrating in great detail what dysphoria felt like for him. You’ll notice that this very much parallels Mae Dean’s work in Epiphany, and it is a larger feature that is almost universal in trans coming-out comics because–and I need to make this very clear for any cisgender people in the room–gender dysphoria feels nothing at all like we are told it does. These explorations of existential pain exist for a single purpose: to give trans eggs reading them the vocabulary to understand what gender dysphoria feels like. It may be their most important purpose.

From there, Nate moves into an illustration of his coping mechanisms for that dysphoria, and you’ll notice parallels with Epiphany here too. First, minimization–we tell ourselves that we don’t deserve authentic self-actualization. Then, adaptation–we cherry-pick things about our AGAB that we can tolerate, or that we even enjoy.

Then, pure physical dysphoria–our ingrained belief that, physiologically, we can never look the way we wish we looked. This is the common pivot you’ll see in trans coming-out comics because it’s the pivot we almost always make in real life: denial of our needs because we believe we don't deserve that they should be met, and even if we did, we’d never get to be our real selves anyway.

Eventually, as with Epiphany, the breaking-point came. You saw this earlier with Galaxy and in Robin Brooks’ work too, because there is always, always a point for us at which the center can no longer hold. This comes because authenticity is a fundamental human need, in the same way that breathing or human connection is. This crux-moment is when we are forced to pursue our truth–even when we, as Nate did at the time–don’t really know what it is yet… or when our stories end forever, overwhelmed by the shame and self-hatred that the world piles onto us.

Nate’s crux was the forced introspection of the pandemic, the same as mine. And, like me, he found himself grasping, lunging for the things he needed–complete breast removal, in this case–in a way that is plainly out of his control, no matter how hard he tried to hold himself back.

I want to linger on this line–feeling the weight of them–for a moment, not only because it’s the name of the piece and the very heart of it, but because it’s such a perfect, beautiful encapsulation of the reality of a lifetime of living with dysphoria. In a mirror of this, it wasn’t until August of 2021–a year into transition–that I let myself feel the absent weight of the breasts I didn’t have, despite the effects of HRT. I wept on and off for a week as, for the first time, I let myself really feel that absence. I’ve talked to hundreds–maybe thousands–of trans people of every gender you might imagine, and I’ve heard some variation of this story from every one of them. At one point, finally, we let ourselves feel. We accept ourselves. I stand before you only 48 days away from my own second top surgery, because the first wasn’t enough–I’m a bit of Nate’s reverse, in this respect–and if you hear tears in my voice, that’s where they’re coming from. Like Nate hyperconsciously felt the weight of his breasts, I feel the missing weight of them, and it pulls at my heart every moment. It doesn’t make sense. It’s true anyway.

And that’s the function of this section of a trans coming-out comic: to give voice to these indescribable feelings, to know the weight of the parts of our bodies that should or should not be there–and to show the joy, the relief, the euphoria, when it’s finally corrected.

In both Euphoria and The Weight of Them–in essentially all trans coming-out comics–you have this same rhetorical construction: Suppression, self-destruction, an instinctual grasping for truth, then final, joyous freedom from our self-imposed shackles. These comics are a practical guide, certainly–Mae shows us the hows and whys of the questioning process, and Nate shows us the nuts and bolts realities of asking for and getting top surgery, and that you don’t need to have the answers first–but more importantly, they are an emotional how-to. That’s the real work of transition: accepting that your feelings are real, and that you deserve to be happy. Most of us don’t believe these things, and have to learn them. These comics show us how.

Memetic Retransmissions

When we look at these behaviors we also need to look at them in their context. In this way, we can consider them as memetic–now, I use this term in the way Sparby (2017) used it, adapted from Dawkins, as a cultural idea that replicates itself from mind to mind. In this sense, a meme is not a noun, but a verb, a method for transmitting shared consciousness which otherwise escapes easy description. Trans coming-out comics, then, are a vehicle for shared experience, where trans people, hatched or not, can point to them and say “That! That’s how I feel!” with a great sigh of relief. Moreover, they serve to build community after the fact through that same retransmitted shared experience. This distinction is crucial in considering the memetics of these comics, because while they are memetic, they don’t necessarily get shared from one platform to another, one person to another, in the viral fashion that most people think of when they hear the word “meme.” Some do, certainly–but not all, and virality is not a requirement for memetics in this sense. For instance, while The Weight of Them has received enormous attention from the trans community, it never went viral the way that Epiphany did, due in large part to Nate Stevenson’s enormous existing platform. There was no need for virality; everyone could simply see the comic at its source.

Meanwhile, the pandemic lockdowns opened up the “deterioration of self” that Flaherty described and Nate Stevenson illustrated so well in his coming-out comic. Combine those two things–a search for shared identity out of desperate isolation and the memetic vehicle that trans coming-out comics offer–with the privacy to explore yourself, and you get an electric combination, where people could suddenly realize aspects of their identities they’d never otherwise considered. The ripples of this can be seen today, and will continue to impact the world for a long time to come: wave after wave of trans comings-out, overburdened gender clinics, overbooked gender therapists, and surgical wait lists stretching to four years or more.

Classroom Applications

So what does all this have to do with composition classrooms? Well, let’s get back to demographics for a moment. If 5% of your incoming student body knows they’re trans right now, that means that you can expect to have an average of at least one trans person in every composition class you teach. And that 5%? That assumes that everyone who is trans has already figured it out. Let me remind you that I was 35 before I first even thought to question my gender, and that simply existing as a trans person is under massive, desperate legal assault across the nation. Just last month, a Republican candidate for president who will remain unnamed publicly advocated the extermination of every single transgender person in America, every doctor who’s ever helped us, and every teacher who’s ever supported us. Over 270 bills have been proposed so far in America this calendar year, many of which would make it a literal crime for us to go about our lives in public, or which would even simply kill us by taking away the medicines many of us require for our survival, as one bill which is very likely to be passed into law in Oklahoma will. The scale of anti-trans hatred is that bad right now. Because of that bigotry and because so many of us have never yet thought to question our gender, the 5% estimate is almost certainly a significant undercount.

Let me say that again. It is very likely that more than five percent of the population of America is transgender.

If you are a classroom educator and you’re not aware of the realities of your queer students, you’re not going to be able to teach them effectively. If you’re not representing their lives to them, at least from time to time, your content is not going to engage them. And if you’re teaching from a cisheteronormative perspective–that is, the assumption that your students are cisgender and straight–you are telling your queer students that they are abnormal, and that their way of being is inherently less worthy than that of their cis and straight peers. Worst of all, in doing so, you are reinforcing the systemic discrimination which your queer, and especially trans, students face, and which produces, to cite a single example, a poverty rate four times as high as your cisgender students face.

I hope very much that this framing and these ideas sound familiar to you, because if you were to replace ‘queer’ with ‘women’ and ‘cisheteronormative’ with ‘sexist,’ that’s the foundational argument for anti-sexist pedagogy. Antisexist pedagogy is a best practice for a reason, so an anti-cissexist pedagogy should be no less important in the classroom. Representation is how we all imagine a better life for ourselves.

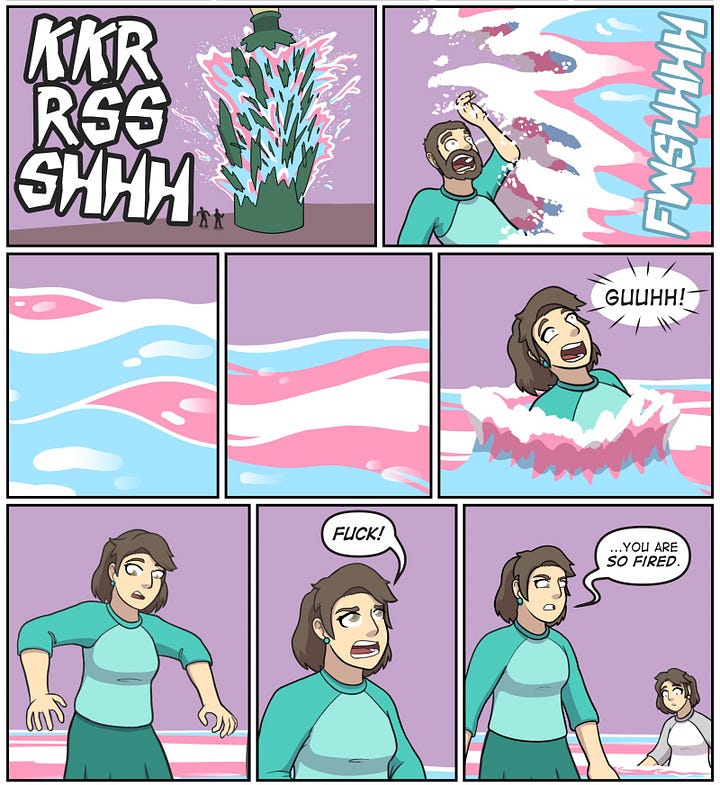

Even aside from questions of equity, trans perspectives offer an excellent pedagogical tool for basic classroom instruction. Consider Robin Brooks’ original coming-out comic, but this time through the lens of an educator trying to teach your students what visual rhetoric is, on a fundamental level. Robin has a discussion with herself, visually representing her fears and anxieties as literal bottles in a discussion of bottling up emotion.Then, with this basic setup, the second page arrives, and it is virtually wordless, with the largest bottle–coded in the colors of the trans pride flag, but the only unlabeled bottle in the comic–exploding and washing over Robin, who is terrified. She emerges two panels later as a woman–as is the avatar for her coping mechanisms–and simply swears in frustration. Nowhere in this comic is it explained that Robin is trans, or that her ability to bottle up her gender failed spectacularly, and in such a way that it will never work again. These arguments are made by the visual display of failure and transformation, and her trans identity is made plain by the repeated use of the trans pride flag and her rejection of the coping mechanism at the end. It’s a clean, clear, simple example of visual arguments which make use of a wide variety of symbols students will be immediately familiar with. It requires virtually no introduction, and is absolutely unambiguous. It is, in short, a perfect teaching tool.

Perhaps the best part is that trans stories are likely to resonate with your cisgender, heterosexual students almost as much as they do with your queer students. After all, who among us hasn’t had that sudden collapse of a coping mechanism, forcing them to deal with a reality they’d been avoiding? It’s part of growing up. More broadly, trans stories resonate well with the general public because when you set aside questions of our gender or our transitions, the realities and emotions we struggle with in hatching and transition are universal: depression, anxiety, self-hatred, self-doubt, fear of judgment, fear of abandonment and, perhaps most importantly, learning to love yourself.

It’s not just students, either. Consider that 5% figure one last time. Then, I would invite you to do a little mental math for the department and the school you work at. Are 5% of your colleagues, to your knowledge, trans? Because unless that answer is yes–and I would be shocked if it was anywhere outside of a Women’s and Gender Studies program–it is a virtual certainty that some number of your colleagues are trans and are closeted, either to the world or to themselves. Conscious and vocal inclusion of anti-cissexist pedagogy is one of the most important ways that you can make your workplace safe for them to begin their journeys.

But make no mistake: trans students will be–probably already are–coming to your classroom in far higher numbers than you’ve ever seen in your career to date. These are our stories. This is how we talk about our experience. This is how we want other people to see our lives. This is how we see ourselves.

This is how you can show us that you see us too.

I finally got to read this post and signed up to Substack so I can write this comment. I came across this post in Mastodon on Friday and as I've generally been very interested in this topic lately (I'm 45, btw), I started reading. After the first two paragraphs I decided to follow the link to Part One: Webcomic. Surely didn't know what was about to happen.

Webcomic post was interesting and therefore I started reading from the beginning of your blog. Went to the Amanda Roman article. Started feeling something strange in my stomach, where I always have physical symptoms when I'm nervous. About this time I got home (was reading these on the bus) and as my wife was home, I pushed the thoughts away. Or at least that's what I tried. The anxiety was still somewhere under the surface.

Yesterday morning I tried not to think about this but felt it in my stomach. When my wife went to work, I bursted into tears. "What the f*** is going on?" I asked myself. I had no choice but to go online and google "How do you know if you're trans?" Some things seemed to fit, others not at all. After I googled "How do you know if you're non-binary?" things started to click.

I think I'm non-binary. The term genderqueer resonates with me. I remember so many times when I've felt like I wasn't the right kind of boy. How I've wished I wouldn't be this emotional. I've had a wonderful therapist with whom we've discussed the gender roles, among other things. Now it all clicked. I've always felt that I don't fit in the box a male should fit. Well, that's because there's a part in me that is male but that's not all there is. I'm more than male.

I kept reading, both your blog posts and other websites, understood more. I knew I had to tell my wife. I was terrified. When she came home in the evening, I asked her to sit down with me. It wasn't easy but I went almost straight to it. I told her that I think I'm non-binary. I explained that I don't feel that there's anything wrong with my body (as that's how I really feel) but that this realization still means a lot to me. I also added that I was afraid of her reaction. She replied with "This doesn't affect how I see you at all." (I'm crying as I'm writing this.) As I told about my feeling that there's a male in me but I'm more than male, she replied with "I knew that." I can't believe this! I love her so much!

During the last half a year, maybe a bit longer, I've felt better than ever. My therapist can surely take some credit for that. We just bought a house with my wife. I'm at a transitional place and feel maybe safer than ever. You mentioned in your post the transitional phases being when people realize they're trans. Yup.

This weekend's been a wild ride and there's still lots to process. I've read about the topic a lot yesterday and today. I'm a big bundle of all kinds of feelings, I've cried a lot. At the same time, I feel like nothing has changed. Now I just understand something more about myself. Many things from my past now make sense! Next, I'll go polish my fingernails. It's something I had a courage to start last year, thanks to my therapist. Now it feels so obvious tell-tale.

I want to thank you for your posts! Without them I wouldn't have realized what I realized yesterday. Sure, it would've most likely happened later but better now. Thank you so much!

I knew from the title I would love this! But also I knew I'd need a tissue lol ;) :)