Foreword: This is a scholarly article that I worked on for the last seven years—two in research and very nearly five in attempted publication—and which was repeatedly rejected by a series of journals and the reviewers at those journals. Some of the most common feedback I received was that reviewers simply did not believe my results. Unfortunately, as this research was performed with human participants and under an Institutional Review Board’s oversight, it is not ethical to publish research results which are more than five years old, so it is no longer possible for this article to see print before that deadline passes.

I am presenting it here as a non-peer reviewed piece of research, in the hopes that it will be useful to someone, somewhere.

There is an archive of different designed syllabi and classroom prompts at the end of the article.

Introduction

It has become increasingly clear over the past decade that common conceptions of the syllabus as a contractual document (Fornaciari & Dean, 2014; Nilson, 2010; Parkes & Harris, 2002; Smith & Razzouk, 1993) is factually incorrect (Collins v. Grier, 1983; Gabriel v. Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, et al, 2012; Miller v. Loyola University of New Orleans, 2002; Miller v. MacMurray College, IL, 2011; Rumore, 2016; Womack 2017). Despite its inaccuracy, this belief persists, though why it does is the subject of considerable debate. Some argue that when a student fails a necessary class, a few appeal that failure, using the university grievance system, and occasionally the legal system, to try to force the matter (Nilson, 2010; Rumore, 2016). Instructors then typically add a new clause in the next semester’s version of the syllabus in an attempt to keep these challenges from recurring, avoid student complaints and grievances, and lawsuits in extreme cases (Nilson, 2010). Others take the position that the contractual syllabus arose as the result of administrative meddling, and that these syllabi have been misunderstood in the larger work towards better pedagogy (Fornaciari & Dean, 2014), that instructors are unsupported and therefore unable to integrate better practices (Lillege, 2019), or simply that instructors are often much less in touch with the needs of their students than they think they are (Davis & Schrader, 2009)—all classic usability problems, in other words. Regardless of the specific cause, syllabi now often stretch to astonishing lengths; Womack (503) notes that syllabi are now often 10, 15 or even 20 pages of dense legalese, and some stretch well beyond even that.

As syllabi have become more and more bloated, students have responded in an unsurprising way: They have largely stopped reading the documents, and increasingly disengage from classroom documentation as a whole. This phenomenon has now been well-documented interdisciplinarily (Fornaciari & Dean, 2014, Harnish & Bridges, 2011; Ludy et al.; 2016; Wasley, 2008, p. 1; Womack, 2017).

This paper answers Womack’s (2017) call for additional research into usable, accessible classroom documentation, and extends Chong’s (2016) and Sauer’s (2018) calls for better usability instruction in the classroom by showing the quantitative benefits of using industry-standard approaches to technical documentation and usability in our classroom documents. It does so by providing evidence from a completed experimental study designed to evaluate the outcomes of providing documents designed to promote student engagement. It then offers a discussion of the implications of this data for instructors in higher education.

1. Background and Terminology

Contemporary syllabi fall into one of a two broad categories. The first and most common is generally referred to as a contractual syllabus, but is also known as a pseudo-legal syllabus (Ludy et al., 2016; Nilson 2010; Womack, 2017). A contractual syllabus is characterized by extensive detail, broad scope, legalistic language, and generally quite a large size, with classroom policies spelled out in exhaustive detail—10-20 pages of text is common. Some contractual syllabi may use cooperative language, and some may use legalistic language; some may use graphics, and some may be plain. The type of language or the look of the page is not relevant—what makes a syllabus contractual is the intent of the document. Fundamentally, contractual syllabi assert an instructor’s control over the course and, thereby, the students in it (Baecker 1998).

The second category of syllabus does not have a consistent name. Ludy, et al. (2016) refer to it as an engaging syllabus, while Womack (2017) describes it as an accessible syllabus; other terms, such as graphic syllabus, crop up as well. Inconsistent terminology is a major barrier to ongoing discussion on improved syllabus development; it is essential that scholars examining syllabi settle on a common term. To simplify, we propose a more universal term: The designed syllabus. We believe that ‘designed syllabus’ describes in concrete, actionable terms what an instructor needs to do to create such a document: design it to be used.

Designed syllabi are typically shorter and often use imagery in place of or to complement text in a way which generally conforms to the principles of Universal Design (UD), from which the name derives. In some cases, there are discussions of classroom policy, but designed syllabi generally work very hard to use personal, accessible, cooperative language (Persson et al, 2015; Womack, 2017, p. 512-515). UD offers a number of advantages in centering the needs of disabled student-users—it integrates disability needs into the core function of documentation, makes crucial information easier to find at a glance, and has the incidental benefit of, as UD has repeatedly demonstrated with common disability-sensitive real-world adaptations like curb cuts, automated doors, and elevators in every multi-floor building, making that documentation easier to use for abled student-users as well. Setting aside questions of language or appearance, which can make a designed syllabus easy to recognize quickly, the defining intent of a designed syllabus is to engage students. A typical designed syllabus, seen in Fig 1, was used in this study.

1.1 A Brief History of the Evolution of the Syllabus

Predating both contemporary types of syllabi was a third, which I refer to as Traditional syllabi, and which have been functionally extinct for several decades. Traditional syllabi, which were brief, often two- or three-page documents which described little more than due dates and reading lists. were a mainstay of classrooms across all disciplines from the first development of formal syllabi as a genre in the early twentieth century, but the specific date of that genesis is not entirely clear. Beginning in the mid-1990s, however, the traditional syllabus began to give way to the contractual syllabus (Mateja & Kurke, 1994; Smith & Razzouk, 1993). Parkes & Harris (2002) documented this transition in 2002, when the concept of syllabus-as-contract had almost completely overthrown the traditional syllabus.

The rise of the contractual syllabus appears to have been rooted in the sad perception of students as the enemy of the college instructor. Smith & Razzouk (1993) argue that

students… use the syllabus document to decide whether they should enroll or stay enrolled in a particular course. Therefore, it can be assumed that those who stay enrolled or enroll in a course implicitly acknowledge knowing of and agreeing to the ‘terms’ of the syllabus as drafted by the instructor (1993, p. 215),

which has become the foundation of the idea of a contractual syllabus. This analysis buries the lede, however; Smith & Razzouk continue, “It is now just as common an occurrence near the end of an academic term for students to fill out a student evaluation of the teacher's effectiveness” (1993, p. 215). In no way, shape, or form are contractual syllabi created for the use of students, nor have they been since their inception.

Later, Parkes & Harris noted, “for instructors, this contract perspective is particularly helpful in settling formal and informal grievances, (2002, p. 56)” and attempt to draw upon legal precedent, in the form of Hill v. University of Kentucky, Wilson, and Schwartz and Keen v. Penson, both decided in 1992. However—and, bafflingly, the authors acknowledge this—“in neither case were the syllabus issues decisive (2002, p. 56).” Their assertions seem to have been accepted broadly and without significant argument until quite recently.

Designed syllabi have come to some attention in recent years (Ludy, et al., 2016; Womack, 2017), largely as a response to the real-world failures of the contractual syllabus—most particularly that students rarely ever read or understand the basic information presented in contractual syllabi. Designed syllabi align with a larger movement outside of syllabus studies and align with the work, for example, that Worthy, et al. (2018) are doing on dyslexia. Further, they represent a larger intent to meet students where they are and which generally “work against the reduction of writing to written products” (Dunn, et al., 2017, p. 121). Designed syllabi remain relatively rare, in part because some degree of expertise in Universal Design is often required to produce them. More significantly, however, many instructors remain wary of their students’ litigiousness, worrying that a less-contractual syllabus will leave instructors exposed. As such, it is worth examining how a syllabus of any kind can, and cannot, protect an instructor.

1.2 Syllabi and the Law

Because so many instructors are concerned about their students’ ability to litigate the syllabus (Mateja & Kurke, 1994; Nilson, 2010; Parkes & Harris, 2002; Smith & Razzouk, 1993), either in the courts or before university administrators, it is important to review what American courts have actually said on the matter. Rumore, in particular, has performed an astonishingly thorough search of the legal literature as it pertains to syllabus design. While their focus is on pharmacy programs, the study’s findings are easily generalizable. Rumore reports that “the courts have consistently ruled that a syllabus is not a contract,” (2016, p. 2) and explores several rulings in detail, as they are foundational to modern jurisprudence on these documents. Collins v Grier (1983) provided a foundational ruling that “there is no contract between a professor or instructor and a student created by the syllabus or university guidelines” (2016, p.2) The most notable case law which follows is Miller v. Loyola University of New Orleans (2011), where the courts legally defined a syllabus as “not contractually obligate[ing] the college, but instead [provides] a variable metric” (cited in Rumore, 2016, p.3) A year later, in Gabriel v. Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, in 2012, a Vermont court found that there is no legal support for treating a course syllabus as a contract whatsoever. Each of these court cases found that clearly announced and consistently enforced classroom policy constitute legal standards, and that any discussion of such policies in a syllabus shows only an intent to enforce, not the actual enforcement of, those policies. Rumore closed with a remarkably clear summary of the legal reality of the situation: “Contracts are legally enforceable documents; syllabi are not” (Rumore, 2016, p.5)

Courts have consistently ruled that there is an actionable business relationship between the student and the university itself, and there is one between instructors and the university, but not between students and instructors (Rumore, 2016). Because the syllabus is not a legal document in the eyes of the courts, administrators’ ability to enforce it as though it were must be governed by academic freedom and oversight policies written into individual or union employment contracts, rather than contract law as it directly applies to the syllabus. While this reality is liberating in many respects, viewed from an alternative perspective, it can be worrying: If a syllabus is not a contract, no syllabus, no matter how comprehensive, can protect any instructor.

1.3 Prior Empirical Research on Contractual and Designed Syllabi

Research to this point on syllabus design has been in some cases scattered and, in some cases, consistent—often between many disciplines. Every empirical study uncovered in the review of the literature identified contractual syllabi to be the worst possible option (Becker & Calhoon, 2009; Harnish & Bridges, 2011; Ludy, et al, 2016; Richmond, et al., 2019; Womack, 2017). Each of these studies has identified that plain, cooperative language helps students, though the degree to which they are aided and the metrics by which that benefit is assessed vary.

Ludy et al. (2016), found significant gains in student impressions of both the instructor and the syllabus in the use of designed syllabi, and in student interest in course material. They also found that a more visually striking syllabus made an immediate positive impression on virtually every test participant they evaluated. Womack (2017) identifies a variety of critical accessibility issues commonly present in contractual syllabi and demonstrates robustly that designed syllabi remediate those issues to an all-but-universal degree.

Richmond et al. (2019) evaluated a variety of empirical studies in psychology before proceeding on to their own work, noting that Saville, Zinn, Brown, and Marchuk (2010, cited in Richmond et al, 2019) and others found that longer syllabi resulted in improved student perceptions of instructor expertise, which Harrington and Gabert-Quillen (2015, cited in Richmond, et al., 2019) corroborated. Harrington and Grabert-Quillen (2015, cited in Richmond, et al., 2019) found that “the length of syllabus plays an important role in syllabus design but… images do not” (Richmond et al., 2019, p. 12), which sharply contrasts the work of Ludy, et al. (2016), and Womack (2017)

This problem is resolved by examining the methodology of each study. Richmond, et al., Saville, et al., (2010) and Harrington, et al., (2015) all rely on subjective evaluations of syllabi that do not occur in a classroom and therefore are not in an instructional context. Thus, these studies did not measure real student engagement or performance.

Ludy, et al. (2016) and Womack (2017) situated their work in a real, representative classroom setting. Situating a study in as close to a real environment as possible will produce more realistic results. Because Saville, et al., (2010) and Harrington, et al., (2015) are not situated in a real classroom context, they are unable to measure real impacts on students, only participants’ impressions. Conversely, Harrington, et al., (2015) reported that longer syllabi produced not only a positive impression on participants, but that their participants consistently read long syllabi—an observation in contrast to many instructors’ experiences in the classroom. As such, their findings should be tempered with caution.

A crucial note here is that all prior study of syllabi that we have been able to find has been of the syllabus in isolation from other classroom documents, which we find to be somewhat puzzling. It seems that prior researchers, from Ludy, et al. (2016) to Baecker (1998). to Harrington et al. (2015), and many more, have considered the syllabus to be a sort of freestanding document which influences and is influenced by the class it describes, but which is essentially released into the class at the beginning of a semester and then left as a sort of monolithic entity. Given the degree to which syllabi are mutable once the course begins and given also the fact that assignment prompts which follow essentially expand upon and clarify the information originally presented in syllabi—an instance of rhetorical amplification if there has ever been one—it seems to us that there may be a more accurate way to think about syllabi, structurally-speaking. If we consider the syllabus instead as a living document which is periodically released to a classroom as its constituent components—assignment prompts, quizzes, and so forth—become relevant, it both adds to the rhetorical complexity of the syllabus and simplifies our understanding of the rhetorical function of classroom documentation of all kinds.

The one universal strain that runs through every commentary on syllabi is that they are instructional documents. This point seems to be undisputed—the authors could find no work on syllabi which claimed otherwise—yet the quantitative research on how they function as instructional documents is incredibly thin on the ground. Given these realities, it is both understandable and baffling that so much research has been done on syllabi outside a classroom setting. Ludy, et al.’s (2016) and Womack’s (2017) work is excellent in this regard, but more needs to be done.

If a syllabus is part of a larger documentary whole within a given classroom, and if that documentary whole’s objective is to instruct students who are unfamiliar with the material which is being presented, scholarship on usability and instructional design in technical writing offers best practices to guide our understanding and sound experimental design to measure these differences. Presenting and testing instructions to an unfamiliar audience is a central concern in technical writing, and by bringing an outside perspective to this problem, we may consider it anew.

Kostelnick (1990, 1994) argues that the visual design of a document is foundational to its function, and that that visual design teaches users how the document is meant to be used in the first moments of its consumption. Conventionally, this has meant that levels, headers, subheaders, and the like allow users to effectively signpost their way through complex documents (Kostelnick 1990, 1994). This corresponds to observed student use patterns of contractual syllabi (Becker & Calhoon, 2009; Ludy et al., 2016). Graphical elements can substantially enhance users’ ability to do this, and can allow technical communicators, like university instructors, to more efficiently and effectively communicate specialized, technical, or complex information. These strategies effectively translate to college writing instruction (Bush & Zuidema 2011, Bush & Zuidema 2012), and can therefore be generalized much more widely. Finally, the effectiveness of a document is reinforced by other documents which are constructed as part of a documentary whole (Schneider, 2005), which reinforces the reconceptualization of a syllabus as a multi-part, living document.

All of these items can be effectively measured through usability testing, which also offers clear guidance for iterative improvement of documentation (Bush & Zuidema, 2012; Redish & Dumas as cited by Schneider, 2005). Testing for usability-focused iterative improvement occurs most effectively in the real-world environment where the documents will be used. Therefore, real classroom monitoring of pedagogical documents is the best way to test their usability, as we have already seen in Ludy et al. (2016) and Womack (2017).

What works in technical writing for diverse audiences has translated accurately to classroom instructional design in a host of other ways (Bush & Zuidema, 2011; Bush & Zuidema, 2012; George, 2002; Ludy, et al., 2016; Schneider, 2005), but classroom instructional documents, like the syllabus, are discrete, testable, and the focus of extensive professional debate among university instructors. Because of these factors, it is not only possible to test whether these principles have the effects that scholarship in technical writing predicts, it may serve as a first step to finally settling a decades-long academic argument as to what sorts of student-facing classroom documents work well

2. Methodology

This randomized, repeated measures, control-group study tested a suite of designed syllabi and instructional prompts against a contractual syllabus and accompanying documents used in a typical advanced composition classroom populated by a representative mix of upper-division students. In doing so, it seeks to quantify the degree to which engagement and/or student performance in the classroom is affected by the form of these documents. These students come from diverse backgrounds, which represent the region of the university well and include a large number of international students. The hypotheses this study tested are:

Students encountering designed classroom documentation will improve their overall performance, as measured by project and end-of-term grades. All grading in each course was holistic, and followed standard grade distributions, such that an A was 93% and up, a B was 83.1% to 87%, and so forth.

Students encountering designed classroom documentation will have improved engagement, confidence, and an improved ability to transfer of knowledge to other courses.

This experimental, repeated measures, two-group design study was administered over a two-year period at Ferris State University, a public comprehensive university located in western Michigan. Participants’ protection was assured by receiving institutional review board (IRB) approval from the university prior to the outset of the study; the IRB determined the study met criteria for exempt status.

A Randomized Control Trial (RCT) based on the principles of usability testing was selected as a method to remove as many variables as possible. The principles of usability testing which this RCT focused on are as follows:

Documents should be designed and delivered in a live classroom environment, to accurately recreate typical classroom use.

Testing should be longitudinal, capturing user response across the whole length of the testing period as much as possible without being intrusive enough to affect participant behavior.

Usability testing should rely on quantitative metrics, or on mixed-methods metrics, so that intervention and control groups are directly comparable.

2.1 Underpinnings

To effectively meet the standards which usability testing calls for, this study was designed with the following core principles:

All testing must be conducted in participants’ real classroom contexts.

To as great a degree as possible, intervening variables have been controlled or eliminated. For example, this classroom study was undertaken by a single instructor, the primary investigator (PI), to remove any possible effects of instructor age, gender, and so forth.

Data collection would not occur within the classroom itself. To maintain a typical classroom environment, all data would be collected from participants online at their convenience.

The objective of these principles was to isolate the effects of designed documentation on students while replicating the real-world classroom environment as closely as possible, and to control for all possible intervening variables. Prior work on syllabi (Ludy et. al., 2016; Womack, 2017) and in technical writing (Bush & Zuidema, 2011; Bush & Zuidema, 2012; George, 2002; Ludy, et al., 2016; Schneider, 2005) predict improved outcomes along a variety of measures for documents designed along these lines. For the purposes of this study, syllabi and assignment prompts are considered as a single, extended, living document which repeatedly addresses the exigence that the classroom presents.

2.2 Inclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible for inclusion in this study if they met the following criteria:

Students were enrolled in a 300-level English composition course at the Michigan university where the study took place.

Students were invited to participate if they registered for the course taught by the PI.

Each student formally consented to participate in the study in writing, after being informed of the participant matter and aims of the study.

Students participating authorized the use of their grade information, anonymously, to determine the impact of the intervention.

Each student agreed to complete five time-sensitive surveys over the course of the semester.

Participants were not eligible to participate in this study if they were not at least 18 years old and/or did not meet all inclusion criteria.

Participants who volunteered to participate were compensated for their time with a small amount of extra credit. Students who were not eligible for inclusion or who chose not to participate were provided with an alternative in-class opportunity for an equal amount of extra credit. All extra credit offered in sections the study examined was applied only after grade information was extracted for the study and, as a result, did not figure into study results.

2.3 Measurement

This study utilized a series of questions which were drawn from major domain areas of the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) tool. The NSSE is used nationally in the USA to assess how students perceive about their experiences in a course and is the most—some would say only—effective tool we have for evaluating student engagement.

The NESSE asks a series of 20 questions which measures students’ self-evaluation of their engagement in a course, seeking to identify how frequently students engage in behaviors or actions which are associated with engagement in educational processes. One such question is: “During the current school year, about how often have you... discussed course topics, ideas, or concepts with a faculty member outside of class?” (NSSE, 2021, NP)

As it is always better to adapt an existing tool than to create a new, untested one, this study used an abbreviated, adapted version of the NSSE (2021) to quantify its results. The NSSE was chosen because it was most thoroughly vetted tool available to track student engagement, and the one which most closely aligned with the investigative aims of this study. The modification here reflects a difference of purpose; the NSSE seeks to map student engagement against actionable, trackable university-level initiatives, and as such the NSSE does not weight its major areas of interest equally. As this study sought to use it as an assessment tool, the NSSE was de-weighted, so that this study could focus equally on each of the five engagement domains which were not excluded earlier. To adapt the function of the NSSE while retaining as much of its proven value as possible, this study modified the NSSE in a systematic way:

Questions about student demographics were eliminated to protect the confidentiality of student respondents.

Questions about instructor and administrator interaction were discarded, because all participants would be taught by a single instructor.

Questions about the nature and character of the institution were discarded, because all participants attended a single university.

Questions about student-student interactions or on-campus activity unrelated to classroom activity were discarded.

Questions which examined participants’ perception of their coursework were discarded, as coursework was standardized amongst all participants during this study.

This left a total of 15 questions which could be used to address student engagement in a variety of aspects of student engagement with classroom activity. To maintain the question-by-question balance of the NSSE, 15 questions were categorized into their core areas of concern and rendered down into a single question for each of the five areas of engagement which preserved all key elements of the original questions. The five key domains were: self-reported direct engagement, regular activity in coursework outside of the classroom, transferability of course information to other contexts, social engagement with others about course materials, and confidence in the ability to perform expected class tasks. These 5 questions were anchored by a 1-5 Likert scale, with 1 being the lowest and 5 being the highest score. The final adapted questions used in the study were:

I’m more engaged on this class, compared to other classes I’m taking this semester.

I’m studying and working on projects for this class on a regular basis.

I’m using course material elsewhere in my life.

I talk to other students about this class frequently.

I’m confident that I can learn and do well in this class.

As a repeated-measures study, the surveys were administered in weeks 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 of a 16-week course. Each survey remained available to participants for one week. Engagement in each of the five tested NSSE domains were a unique, independent measure of engagement.

2.4 Randomization of sections and participants

Students (n=107) in a total of 10 class sections had the opportunity to participate in the study. Each course section was randomly assigned to either the test or control group through use of a die, and all students in each section received either the traditional documents or the designed documents. Students were never informed whether they were in the control or intervention section. Students from any class section had no reason to interact with each other, and the study administrator never mentioned the existence of other course sections. That said, it is possible that members of the control and test group may have had the opportunity to meet, and even discuss, their course materials. This is not a controllable variable in a longitudinal human behavior study.

Participants in the control group course sections received a syllabus built from the Ferris State University College of Arts and Sciences’ suggested syllabus template (Fig. 2, which abbreviates that syllabus), and received traditional-style, text-focused assignment prompts for their three major projects (Fig. 3 represents a typical example). Participants in the intervention cohort received syllabi (Fig. 1) and assignment prompts (for example, Fig. 4) which were designed according to best practices in technical writing. The control documents used parallel language to the intervention documents wherever possible.

Students were recruited from two courses during the study: Advanced Composition and Advanced Technical Writing. While the subject matter of the courses differed, workload, objectives, and expectations of student work did not. Both courses called for three major assignments. These were:

A short-length, wide-audience document which focused on visual rhetoric and audience awareness.

A deep, complex primary-research project which addressed a real-world problem.

A formal long report produced for a real-world client.

These projects were chosen because they represent a wide scope of the possible writing and multimedia assignments which might be assigned in any writing-intensive course, and this study sought to represent that scope accurately.

2.5 Recruitment

The study was announced to students in person, on the first day of class, through use of an IRB-approved script. Students had an opportunity to ask questions about the study, and questions which would not reveal control/intervention status were answered. Students then had one week to read, complete and return the provided informed consent form.

As part of the course, students were hand-delivered paper copies of all test documents. Access to these test documents were also e-mailed directly to their student emails and were made available through a Blackboard course shell. Electronic versions of documents were not made available until paper copies had been distributed. Both test and control documents were distributed in an identical manner, and with identical commentary.

At the beginning of weeks 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 of the semester, participants were e-mailed an invitation to complete a survey using the adapted NSSE tool questions and were informed that the survey would remain available for one week. The availability of the survey was mentioned in class during the open week, and the survey was closed at the end of that week. Responses were not examined before the end of the semester. Participant anonymity in the response process was maintained in two ways. First, Google Forms, the platform which collected responses, does not retain IP information, which could potentially be identifiable. Second, any information which Google Forms did retain was deleted during end-of-term data processing.

At the end of the semester, data from participants who did not complete all five surveys over the course of the semester were discarded. Finally, the study anonymized all identifiable participant information by replacing that information with a randomly generated control number.

The data were then subjected to statistical analysis to determine the following:

Was there a measurable, statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups in any of the five areas of engagement?

If so, was that difference related, to a statistically significant degree, to the intervention?

If so, did the intervention have a measurable, statistically significant effect on student performance in the class?

Any examined relationship which did not meet a two-tailed significance of p≤0.05 were discarded.

3. Results

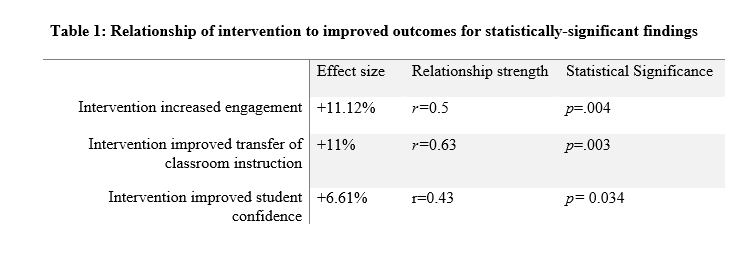

A total of 107 participants met all inclusion criteria for the study, completed all measures and provided grade information. Of these, 56 were in the control group, and 51 were in the intervention group. The abbreviated NSSE weas tested and achieved an R= 0.64 in this study. Summaries of all findings can be found in tables 1, 2, and 3.

Table 1: Relationship of intervention to improved outcomes for statistically-significant findings

Table 2: Relationship of improved outcomes to student academic performance

Table 3: Effect size of outcomes improvements on student academic performance

3.1 Student Engagement

Pierson’s r correlation coefficients were completed, and student engagement had a strong (r=0.5, p=.004) statistically-significant relationship between instructions-style classroom documentation and self-reported student engagement. The intervention group had an overall improvement in engagement of 11.12%, when compared to the control group. Further, the results demonstrated a strong (r=0.54), statistically significant (p=0.005) relationship between improved student engagement and improvement in achievement in the courses, as demonstrated by both end-of-term and individual project grades.

3.2 Work Patterns

Data on student work patterns did not pass an independent samples t-test. As a result, the data were eliminated.

3.3 Student Transfer

Pierson’s r correlation coefficients were completed, and student transfer had a strong (r=0.63, p=.003) statistically-significant relationship between instructions-style classroom documentation and self-reported student transfer. The intervention group had an overall improvement in engagement of 11%, when compared to the control group. Further, the results demonstrated a strong (r=0.65), statistically significant (p=0.004) relationship between improved student transfer and improvement in achievement in the courses, as demonstrated by both end-of-term and individual project grades.

3.4 Talking with Others

There was no statistically significant relationship between instructions-style classroom documentation (p=0.13) and the degree to which students talked with others about classroom materials. The Pearson’s correlation of that relationship was therefore irrelevant.

3.5 Student Confidence

A statistically significant, moderate relationship (r=0.43, p= 0.034) between course documents and student confidence occurred for students in the intervention group, a measured 6.61% increase over the students in the control group. Further, there was a moderate relationship (r=0.47, p=0.043) between the improvement in student confidence and improved project and end-of-term grades.

3.6 Student Performance

As the results of the study uncovered relationships between the documents and increased student performance, it is interesting to examine the overall difference in achievement between the two groups. The control group in this study reported a term grade average of 86.96%, while the intervention group reported a term grade average of 89.19%, an increase of 2.23 percentage points. This difference was tested against the relationships described in sections 3.1, 3.3, and 3.5 with Pierson’s r correlation coefficients. The strengths of those relationships were, respectively, strong (r=0.96, p= 0.005), strong (r=0.65, p= 0.004), and moderate (r=0.43, p= 0.043), all with high confidence.

4. Discussion

Designed syllabi were strongly correlated with how engaged students were in the writing courses they were enrolled in, how confident they were in their own success, and how well they perceived that they could transfer what they knew outside of that classroom. Moreover, these improvements were associated with better student grades—about a full grade increment, in this case from a B average to a B+ average—across the board.

The findings of this study align with and extend with the work of Ludy, et al. (2016) and dispute the findings of Richmond, et al., Saville, et al., (2010) and Harrington, et al., (2015). Both this study and Ludy et al.’s study use a real, classroom setting to test hypotheses, whereas other researchers did not. Principles of effective usability testing predict that the non-real environment which other studies have used would have a major effect on their findings, and our findings support this. This confirms the hypothesis that this study presented in Section 1—that the difference between a laboratory setting and a real classroom explains the disagreement of those studies. Real-classroom situation seem to generate real-use results, whereas a test in isolation appears to result in users performing more as a test administrator would hope that a user act, rather than as they would on a day-to-day basis.

4.1 Limitations

Although the protocol and research plan sought to minimize the impact of intervening variables, it is possible that these may have influenced the study results. For example: Because no demographic data were gathered, per IRB request, it is not known if the control and intervention groups differed in some unknown way. It is also not known if those who completed the study were somehow different than the general population of students in the courses. As well, although the sections of students were separated, because the study was completed on a college campus where some students shared a major or minor, it is possible that participants knew each other and had the opportunity to discuss the study, thereby blurring the lines between control and intervention group. Further, it is possible that Type II errors could have been made, in that the study may have been under-powered. The adapted NSSE tool approached (R= 0.64) but did not reach the level of significance expected (R=0.70). Finally, the PI of the study was also the person implementing the intervention, which may have impacted the results.

5. Implications

Designed syllabi intentionally disrupt the expectation that instructors seek to control and command our students. In doing so, our data indicates that they improve broad-based engagement and performance, all while protecting students with common learning and attention disabilities—exactly the outcomes that Universal Design predicts. We are obliged to pay better attention to how we can use such readily available tools to improve classroom outcomes.

The authors hesitate to single out any single component of designed syllabi as essential to inspire improved student engagement and performance, as syllabi and their supporting documents are rhetorically complex. Saying ‘this or that component of a designed syllabus, be it visual design or language or brevity, improves student outcomes’ is a project at least as complex as this one, and likely several. We feel that the only position which is clearly supported by the data at this time is that designed syllabi as a whole improve student engagement and performance. That said, the simplest explanation for this effect lies in comparing the rhetorical objective of a contractual syllabus against that of a designed syllabus. As many proponents of contractual syllabi have noted, the core objective of those syllabi is to control the classroom (Baecker, 1998; Nilson, 2010). Designed syllabi, by contrast, seek to engage students. It would make a great deal of sense that a syllabus designed to engage does so—and, since student engagement has long been linked to student performance, the benefits of improved engagement would naturally lead to improved performance.

Womack (2017) offers a master class in how and why syllabi ought to be better designed to serve the needs of students with disabilities, and we won’t reproduce her outstanding work here. Rather, we argue that her work should serve as a foundation upon which continuing research in syllabi should build. Womack (2017) correctly founds her argument, in substantial part, on the principles of UD. UD argues that improved design for those with disabilities helps users in the general population, both those with other, unrelated disabilities and abled users alike. In that sense, this work is the first step toward using that work broadly. To that end, we argue that a generalized reading of Womack’s (2017) arguments are of benefit both to instructors and students, regardless of their disability status, and argue that extending the principles she proposes will offer major benefits to students, regardless of their disability status.

Many of Womack’s (2017) arguments center around rehabilitating the language that a syllabus uses—make it more “inclusive” (p. 513), “positive” (p. 514), and “cooperative (p. 514-515). Contractual syllabi are typically “paternalistic” (p. 515), and this sort of authoritarian language sets up the student-instructor relationship as inherently confrontational. If, instead, we work to draft more “user-friendly” (p. 511-512) and “reader-friendly” (p.508-511) text, which is built from the ground up to help students “find agency” (p. 513) and value in the subject matter the course presents, we invite them to invest in the content of the course. By removing barriers to comprehension, as Womack describes, not only do we design for accessibility, we make meaning plain for all students.

That plainness and accessibility of syllabus language allows instructors to communicate meaning more simply, but it is not enough to say a thing in its simplest form—we should also remove items which do not need to appear on a syllabus for a student to be able to succeed in the course. Finally, we need to present what remains in a scannable, quick-reference format, since users of all kinds, not just students, rarely read documents all the way through (Womack, 2017). The more we reduce our text by volume, and the more we format what remains into simple chunks, the more likely our students are to use any given part of our syllabi. It’s worth remembering that students are often receiving four or five of these documents within the first two days of a semester. If each is ten pages of single-spaced text, simple math demonstrates why so few syllabi are ever read; asking a student to read fifty pages on no prior notice in a two-day period is probably hopeless. If each is instead two pages, it is much more likely that students will invest the time they need to. A few examples of how this can be accomplished are:

Reduce your schedules to simple statements of what’s due, and when.

Where any of your policies are identical to the University’s policies, simply say so and move on. Ideally, do so for all such policies in a single statement.

Remove low-stakes classroom policies from your syllabus entirely, and simply talk about them in class.

Identifying such policies is straightforward; ask yourself whether any given policy directly and substantively affects daily student learning for multiple students in the class, or which directly impacts grading categorically. If you find that a policy is mostly the result of a pet peeve, such as how students format their emails or whether they play quietly with their cell phones during class, it is almost certainly low stakes.

Make your headers larger than you think they need to be.

Use a larger font size then you would normally opt for.

Build a clean, clear level structure into your page.

Build your syllabus to reflect a hierarchy of information, where the information your students think is most important comes first, in large text, and things further down the page are progressively less important.

Grade breakdowns are almost always at the top of the list here, as are the texts students need to read to be able to complete the class.

Group similar ideas or items together.

Use visually-interesting, highly-readable fonts.

Avoid Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri which, while functional, are so commonplace that they do not stand out.

Easy substitutes for each exist and are readily-available. Garamond, for instance, is an excellent alternative for Times New Roman.

In short, follow the principles of modern, commercial, user-facing design that technical communication has long known to be highly effective at improving the usability and accessibility for wide audiences.

Finally, Womack (2017) argues for the use of appropriate visuals, and we emphatically agree, because visuals can present complex information in simple ways. Just as importantly, they indicate at a glance the kind of a classroom dynamic students should expect. This study’s syllabus design evokes a comic book, right down to the fonts, frame-styled dividers, and characters, but there is no reason to believe that that particular design—that any particular design—is needed to capture the effects our study find. There is a whole galaxy of options; you could make a pamphlet, or a booklet, or a website, and you could use the visual identity of your university, your favorite sports team, or of any other pop culture artifact you prefer. While the authors used Adobe InDesign® to create all materials described in this study, any design tool—even simple, free ones, like Canva or Adobe Spark®--can achieve excellent results. Even the humble templates and visual design capabilities in Microsoft Word® can achieve a great deal.

Ultimately, the rhetoric of contractual documents is fundamentally about power, not education—a reality which proponents of contractual syllabi are not shy about acknowledging (Baecker, 1998), and which students do not miss. If students’ first perception of instructors is that we are hoarders of power and knowledge, handing down pronouncements from on high, is it any wonder that they respond combatively? In the same way, it is no surprise that in a vacuum, students more highly rate syllabi that most completely fit the genre of the syllabus (Afros & Schryner, 2009), and that they expect they might have to litigate. These are all normal, predictable responses to the implicit rhetoric of contractual syllabi. If instructors show up ready for a fight, students will go looking for their boxing gloves.

6. Conclusion

The evidence this study presents parallels several other studies, all of which demonstrate that designed syllabi have remarkable ability to improve student engagement and performance. We believe that those improvements are achievable for the typical university instructor. In many ways, all this requires is that instructors return to the core of what a syllabus is: an instructional document, and to build it from that perspective. Best of all, this is an improvement an instructor can make without spending an additional extra moment of class time, and which can be readied before a semester begins.

7. Sample Resources

The following resources represent a series of sample designed syllabi and assignment prompts. Most of them employ significant visual design elements, as that is one of the author’s specializations, but highly visual elements are not necessary. None of them are perfect, nor are they presented as such; instead, each attempts to engage with students while also being a model example of the type of work the student is being asked to produce.

Syllabi

Prompts

A booklet assignment prompt for an instructions-writing project

A three-fold pamphlet assignment prompt for a pamphlet redesign project

A booklet prompt for a semester-long instructions redesign project

Bibliography

Afros, E. & Schryner C. (2009). The Genre of Syllabus in Higher Education. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 8(3), 224-233. DOI:10.1016/j.jeap.2009.01.004.

Baecker, D. L. (1998). Uncovering the Rhetoric of the Syllabus: The Case of the Missing I. College Teaching, 46(2), 58-62. DOI: 10.1080/87567559809596237.

Becker, A. H. & Calhoon, S. K. (2009). What Introductory Psychology Students

Attend to on a Course Syllabus. Teaching of Psychology, 26(1), 6-11. DOI: 10.1207/s15328023top2601_1.

Bush, J., & Zuidema, L.A. (2011). Professional Writing in the English Classroom:

Beyond Language: The Grammar of Document Design. The English Journal, 100(4), 86–89. www.jstor.org/stable/23047787.

Bush, J., & Zuidema, L.A. (2012). Professional Writing in the English Classroom:

Let's Get Real: Using Usability to Connect Writers, Readers, and Texts. The English Journal, 102(2) 138–141. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23365413.

Collins v. Grier, 1983 WL 5148, at 2 (Ohio App., July 27, 1983).

Davis, S. & Schraeder, V. (2009). Comparison of Syllabi Expectations Between Faculty and Students in a Baccalaureate Nursing Program. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(3), 125-

131). DOI 10.3928/01484834-20090301-03

Dunn, M. B., Juzwik, M. M., Cushman, E., & H. Falconer (2017). Toward

Rich Accounts of Writing Development. Research in the Teaching of English, 52(2)117-121. jstor.org/stable/44821480

Fornaciari. C. J. & Dean, K. L. (2014). The 21st-Century Syllabus: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. Journal of Management Education Vol. 38(5), 701-723. DOI: 10.1177/1052562913504763

Gabriel v. Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, et al, 2:12-cv-14 (MA District Court. January 12, 2012).

George, D (2002). From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing. College Composition and Communication, 54(1) 11–39. jstor.org/stable/1512100.

Harnish, R & Bridges, K (2011). Effect of Syllabus Tone: Students’ Perceptions of Instructor and Course. Social Psychology of Education, 14(3) 319–330. doi:10.1007/s11218-011-9152-4.

Kostelnick, C (1994). From Pen to Print: The New Visual Landscape of Professional Communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 8(1) 91–117, doi:10.1177/1050651994008001004.

Kostelnick, C (1990). The Rhetoric of Text Design in Professional Communication. The Technical Writing Teacher 18(3), 189-202. eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ421258.

Ludy M-J, Brackenbury, T., Folkins, J., Peet, S., Langendorfer, S., & Beining, K. (2016). Student Impressions of Syllabus Design: Engaging Versus Contractual Syllabus. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2). doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2016.100206

Lillge, D. (2019). Uncovering Conflict: Why Teachers Struggle to Apply Professional Development Learning About the Teaching of Writing. Advances in the Teaching of English 53(4) ncte.org/journals/rte/issues/v53-4.

Mateja, K, & Kurke, L.B. (1994). Designing a Great Syllabus. College Teaching, 42(3), 115–17. DOI:10.1080/87567555.1994.9926838.

Miller v. Loyola University of New Orleans, 829 So.2d 1057 (La. Ct. App. 2002).

Miller v. MacMurray College, IL. App (4th) 100988-U (Filed Oct 5, 2011).

National Survey of Student Engagement (2021). Survey Instruments: NSSE. Retrieved May 10, 2022, fromnsse.indiana.edu/nsse/survey-instruments/index.html.

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors, (3rd ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Parkes, J. & Harris. M.B. (2002) The Purposes of a Syllabus. College Teaching, 50(2), 55–61, DOI: 10.1080/87567550209595875.

Persson, H., Åhman, H., Yngling, A.A. et al. Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: different concepts—one goal? On the concept of accessibility—historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Univ Access Inf Soc 14, 505–526 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0358-z

Richmond, A. S, Morgan, R. K., Slattery J.M., Mitchell, N.G., & Cooper A.G. (2019). Project Syllabus: An Exploratory Study of Learner-Centered Syllabi. Teaching of Psychology, 46(1) 6–15, DOI:10.1177/0098628318816129.

Rumore, M. M (2016). The Course Syllabus: Legal Contract or Operator’s Manual? (Report). American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 80(10) 1-7 doi:10.5688/ajpe8010177.

Schneider, S. (2005). Usable Pedagogies: Usability, Rhetoric, and Sociocultural Pedagogy in the Technical Writing Classroom. Technical Communication Quarterly, 14(4) 447–67. DOI:10.1207/s15427625tcq1404_4.

Smith, M. F., & Razzouk, N. Y. (1993) Improving Classroom Communication: The Case of the Course Syllabus. Journal of Education for Business, 68(4) 215–21. DOI:10.1080/08832323.1993.10117616.

Wasley, P. (2008). The Syllabus Becomes a Repository of Legalese. Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(27), A.1-.

Womack, A-M (2017). Teaching is Accommodation: Universally Designing Composition

Classrooms and Syllabi. College Composition and Communication, 68(3), 494-525.

Worthy, J. Lambert, C., Long, S. L., Salmerón, C. & Godfrey V. (2018). ’What If We Were Committed to Giving Every Individual the Services and Opportunities they Need?’ Teacher Educators’ Understandings, Perspectives, and Practices Surrounding Dyslexia. Research in the Teaching of English, 53(2), 125-148.

That was a great read, and one of the most accessible academic papers I've read. (I read academic papers in various fields out of personal interest. I'm that much of a nerd.)

It reminds me of a branching trend from my later academic years. When I got my first two degrees, instructors used transparencies on overhead projectors. Later, when I went to a technical college (which became a polytechnic university), Power Point was just coming into wide use. I saw many examples of bad presentations. You know the ones: small text crammed onto every slide, read verbatim by the instructor.

Even worse, our Technical Communications course featured a presentation (which apparently cost the college several thousand dollars to use) that advocated using every high-contrast color combination, every slide transition, every animation in the toolkit, and having an image on every slide, regardless of whether it enhanced the information, or was even related to it. I learned a lot from that presentation: How *not* to design a slide deck. (I couldn't believe that presentation wasn't ironic!)

Then there was my Math instructor. His slides complemented his presentation, rather than duplicating it. His titles and text were large, clear, and concise. And the way he used animations to precisely illustrate geometric relationships has inspired my presentation style ever since. I've never studied Universal Design, but I'd guess that Scott's presentations ticked many of the boxes.

As I've gotten older, I've become more interested in readability in written materials, both in print and online. As a safety person, clear, immediately-visible communication is essential. I have a couple of comments on the accessibility of your sample documents.

- The header font on Technical Writing Syllabus 2 might not be as effective for older or visually impaired students. The serifs make up 80% of the letters!

- The title on the Redesign Prompt New pamphlet is superimposed on a full-color image. With text that big, it's not a significant barrier (and the shadow definitely lifts it off the background), but for someone with ADHD or dyslexia, it can delay comprehension. I looked at the title three times, seeing "Red Ensign" for some reason.

Overall, however, if I had been given syllabi that looked like that in university, I might actually have retained the information, rather than snoozing through it the first time and having to search through it later to find what I missed. I read everything including online terms of service. Good design makes it so much easier!

The term "contractual syllabus" helps distill an unease I have felt deepening over my decades-long career as a university classroom instructor.

Students -- or at least, lots and lots of students -- seem no longer to enter the classroom with a foundational trust that the instructor has their best interest at heart, knows what she is doing, and makes decisions about the course accordingly.

Many students instead have absorbed the mindset that university instruction is a product; that they are *customers*; and that the job of the instructor is generate in them an experience of 'customer satisfaction'.

I hate it. I like discussing and sharing ideas with students: that's why I like teaching. I have no patience for being addressed like a short order cook who allegedly f*cked up an order of fries, by a customer who now demands a re-do, on pain of going over my head to speak to the manager.

Writing for The Atlantic, Caitlin Flanagan described such stand-offs pungently: "they wanted me to change the grade; I wanted them to drop dead". (*)

I used to be shocked. Now I am just dismayed.

I don't blame the students. They are young: they are reflecting back the culture they find at the university, and in the larger world.

In response to such complaints, demands, and haggling, I found myself increasingly treating my syllabi as contractual documents. I wanted to anticipate and head off every conceivable pain-in-the-ass complaint the most entitled student might come up with.

Unfortunately, as you articulate so well, this approach degrades the educational environment and experience for all students. I realize that I have allowed the whiniest, most entitled, must anti-intellectual students to set the initial tone for the whole course, to an unacceptable degree.

More unfortunately, I've basically given up. Pressed between a noisy minority of students emboldened in their customer-driven entitlement, and a wholly indifferent if not meddling administration, I've mostly stopped accepting classroom teaching jobs.

Instead, I look for other opportunities to engage in intellectual sharing with other human beings.

Thanks for sharing your intellectual work with us.

----

(*) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/04/private-schools-are-indefensible/618078/