It’s kinda scary to be trans these days.

In a lot of places around the world, at least one national political party has decided to make “being shitty to trans people” a core part of their political platform, whether it’s Project 2025, Alberta’s exclusion of trans youth from basic gender-affirming healthcare, or the Cass Report. Why? Well, there’s a bit of a Kansas City Shuffle going on among conservative lawmakers around the world, but the short version is that modern demographics don’t favor conservatives in the long term. Young folks are self-identifying as queer at unprecedented rates—seriously, as much as 30% of Gen Z women are bisexual, pansexual, or omnisexual, with over 20% of all Gen Z folks saying they’re some version of queer—and for conservative political parties with decades-deep reputations for being anti-LGBT, those demographics look scary. If they don’t do anything, within another decade or so, they’ll be unable to win another election.

Like… ever.

So they’re trying to shove us back into the closet, like they are. They figure, if they can make us hate ourselves like they hate themselves, they can get us to vote for them. Yeah, I know it sounds stupid, but believe it or not, it’s sound psychology—the process is called reaction formation, and in a nutshell it’s where someone reinforces their own self-hatred by hating people just like them in a really loud and public way. It’s why so many anti-gay politicians and ministers and whatnot get caught having gay sex all the time.

They’re hoping to lock things down the way things are right now, have a nice, cold pint, and wait for all of this queer stuff to blow over.

It’s a ludicrous idea, to be absolutely clear. It won’t work.

But none of that helps trans folks right now, though, even as acceptance for queerness in general steadily rises around the world. We’re a small minority, whatever estimate of our population you go with, and that makes us pretty easy to single out and demonize, because we don’t have much political, social, or financial power to fight back.

But we fight back anyway.

Getting their attention

So, you’ve been posting advocacy comics on Instagram, writing pithy tweets, skeets, or toots, and all your queer friends agree that they kick ass, but when you talk to the cishet people in your life, saying the same things, they just… don’t get it. Why don’t they get it?! Our lives are on the line here! Why don’t they care?!

Maybe one of the most common frustrations when people start dipping their toe into advocacy work is what feels like a total brick wall right at the start, where they can’t make any progress at all towards their goals. What’s worse, it often feels like trying to make those arguments does more harm than good, pushing the people we want to persuade away from us, rather than drawing them in to deeper allyship.

Well, there’s a reason why rhetoric is a whole field of study, with PhD’s and stuff.

So, let’s talk about the fundamentals of effective pro-trans persuasion. And remember: arguing is a good thing! Persuasion helps people form and maintain community.

The available means of persuasion

If you went to college, you probably had to take a Freshman Composition class, and in that class, they probably talked about some basics of rhetoric. If you’ve forgotten absolutely everything else, you probably remember the four basic Ancient Greek persuasive appeals:

Logos: To persuade using evidence, reasoning, and logic

Ethos: To persuade using your reputation and character as a person.

Pathos: To persuade based on the audience’s emotions and compassion.

Kairos: To persuade by making the case that now is a uniquely opportune time.

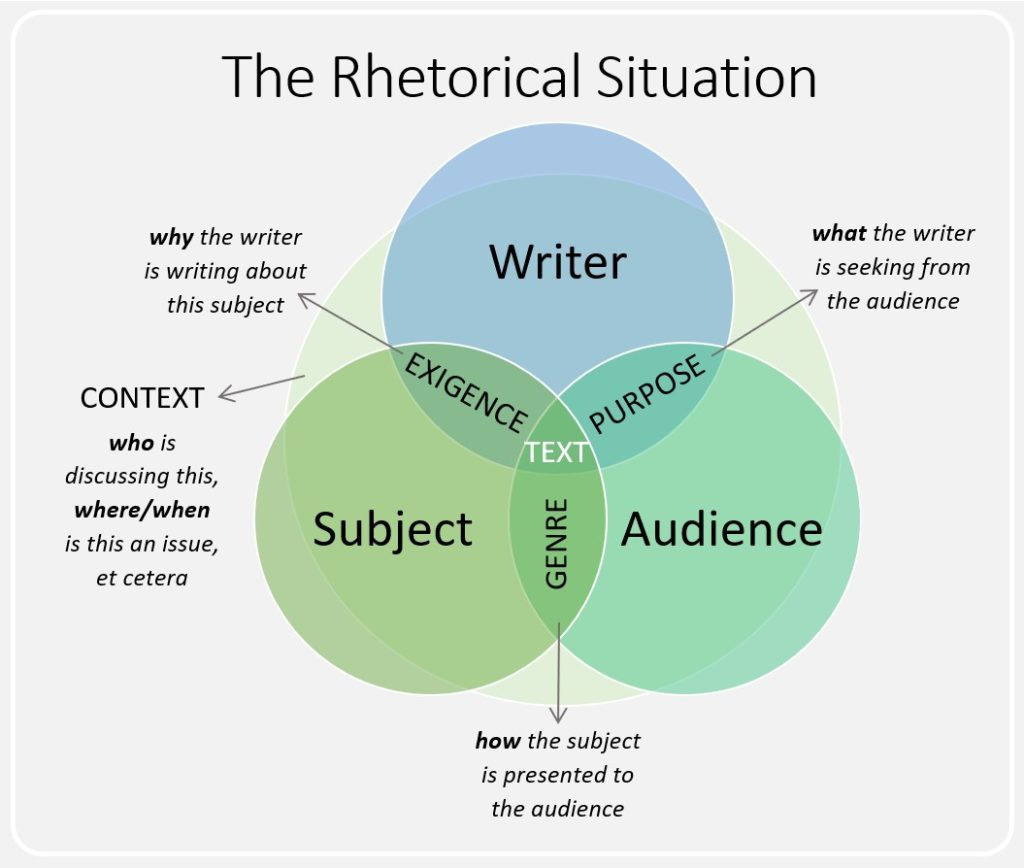

For clarity, before we keep going: the Greek model is too simple, to the point that it’s definitely wrong, but it’s wrong in parallel with what we know to be right, so these ways of looking at persuasion are useful because they help us break down the incredible complexity of the rheotrical situation into something more bite-sized.

And, for clarity, the rhetorical situation is still the easy Big Idea in rhetoric. Don’t even get me started on stuff like terministic screens.

We are a living, breathing part of the rhetorical situation. Who and what we are have a decisive effect on what arguments we can and can’t make, if we want to persuade people—there’s that ethos, paralleling reality, but not quite being 100% right. What we’re arguing about further limits our choices, because we need to stick to what’s factually true, unless we don’t mind screwing over our ethos in the future—there’s our logos parallel. Who we’re arguing to limits it even further, because not all people can be persuaded by any given argument—our pathos parallel. Finally, the context, within which all this happens—our kairos parallel—limits when and where any given argument will work.

That means that the reason your arguments aren’t working? They’re because you’re misinterpreting the rhetorical situation.

Let’s fix that.

Being a better rhetor—Ethos

When we step out of the written word, we have to trade “writer” for “rhetor,” which just means “a person who’s making an argument.” It’s just a more general term.

When we’re trying to be a better rhetor, and give our ethos a boost, we need to look inward and understand ourselves a little better. One of the most important things that trans folks need to get before their arguments can work well is that we tend to get pushed pretty hard to the political left when we come out and transition. It’s not some brainwashing thing—we just tend to be poorer, better-educated, and get hit with the shitty side of our capitalistic social structure, all of which pushes voters toward more liberal or leftist political positions. Given that we tend to hang out in groups, particularly online, we get hit pretty hard with the echo chamber effect, which reinforces socially-common political biases through self-sorting.

In simple terms? It means that by hanging out with a bunch of other trans folks, we tend to get entrenched in political stances that are common in the trans community. It’s the Fox News Grandpa effect.

And I’m guessing that it makes you feel a little uncomfortable to hear that.

This is the first and most important thing you need to face if you want to persuade people outside of your social bubble effectively: you are not immune to persuasion or propaganda. You have absorbed a lot without noticing it over the years, both before and after your transition. And those things? People have noticed them, and noticing those things has colored their view of you as a person and a rhetor.

Put a different way: if they know you have a history of arguing for what they see as hard-left stuff, stuff they think is a bad idea, they’re going to treat other things you argue for with a degree of pretty understandable skepticism.

To be a better rhetor is going to take some time and effort, but it’s worth doing not just because you’ll become more persuasive, it’ll help you fight your own radicalization. Here’s some good places to start:

If you grew up religious, and especially if you grew up evangelical, it’s an incredibly good idea to start working on deconstructing the sense of moral perfectionism that you almost certainly grew up with. It’s a central force of internalized white supremacy and a powerful radicalizing force, and more importantly it keeps you from willingly compromising. Compromise is the very heart of argumentation.

A really good example of what happens when you don’t take this apart inside of you is single-issue voting. The rabid anti-abortion crowd, who doesn’t care one whit about anything else on the ballot? The folks who refuse to “sully their vote” over Biden’s reprehensible handling of Palestine even though Trump will be immeasurably worse for Palestinians if he’s elected? That’s moral perfectionism: if they don’t get exactly what they want, no matter how impossible, they’ll take their ball and go home, rather than take the step-by-step improvement that moves things toward what they want.

Diversify your friend group, and diversify where you get your news and takes. This isn’t just about getting out of your echo chamber—it also helps you understand the people you want to persuade better. If you aren’t curious about them, they can hardly be expected to be curious about you.

No, I’m not saying to make friends with transphobes. On the other hand, if your entire friend group is queer and you feel like no significant news source can be trusted, that’s what radicalization looks like.

Related: don’t expect moral perfection from your news sources. Not only won’t you get it, expecting it will radicalize you.

Work to be a better listener. Yeah, I know it seems silly, but very few people are good at being active listeners. People are more likely to listen to you when they feel that they’ve been heard out.

If your audience thinks you’re a radical, a loony, a weirdo, they’re not going to listen to you no matter what you say. Better yet to not actually be one.

Know your subject—Logos

One advantage we have as trans folks in this place and time is that it’s hard to live as a trans person without getting an up-close, personal understanding of how the various laws and bills that the jerks are advocating will affect us—but a lot of us stop there. When we hear about bathroom bills, we worry about where we’ll pee, and what people will do if we try, but it’s really easy to forget that these bills don’t only affect us. They’ll get used to harass a whole lot of cis people.

And, as much distrust as a lot of our legal system deserves these days, especially in the US and the UK, many or most of these bills and laws are wildly illegal, in and of themselves. Florida’s high-profile bathroom law is a really good example here, because I couldn’t find even a single record of it actually being enforced. Why does that matter? Under US law, nobody is allowed to sue to get it thrown out as the unconstitutional garbage it is until someone is harmed by it. It’s still getting challenged in court for sure, but until someone is actually arrested under it, that lawsuit will probably fail because of standing. A good analogy is Mississippi’s cohabitation law, which makes it a crime for an unmarried man and woman to cohabitate. It’s obviously unconstitutional, but it hasn’t been enforced in decades, so there’s nobody alive who actually has legal standing to challenge it. On the other hand, all of the Florida anti-trans laws from the big push a couple of years ago that were enforced, like the trans healthcare exclusion, have been thrown out.

The things we’re fighting, in other words, exist in a bigger context, and when we zoom in too far and ignore that context, we sound like Chicken Little, screaming in panic over a sky that very plainly isn’t falling.

That means that we need to know not just about the things we want to advocate against, but how they actually interact with existing laws, and whether or not they’ll be enforced—and who they affect other than us.

Who are you trying to convince?—Pathos

You can’t convince everybody. Period. Some rhetorical situations are arhetorical, meaning that no argument of any kind could change the mind of your audience.

And the thing is? A lot of people will argue with you just to spread their ideas. You need to have a real interest in who you’re trying to persuade, to work to understand them and learn, beforehand, whether they’re even persuadeable.

But let’s say you find someone who you could convince. You probably have, many times before. Before any argument you could make could persuade them of anything, you need to learn what they think, feel, believe, hope for, and fear.

You need to listen. Actively.

When you make an argument, it needs to not speak to your reality, needs, or fears, it needs to speak to theirs. And yes, that’s why it’s so hard to get cis people to care about anti-trans legal measures in any concrete, get-up-and-do-something sort of way: as long as it’s about you getting hurt, it really only matters to their lives in an abstract way. Some folks will care in a meaningful way, but if they do, they’re probably on our side anyway, and don’t really need convincing.

Just as importantly, you need to understand that arguing from evidence? It doesn’t really work, except as a supporting thing. Evidence doesn’t change belief—it justifies it, and arguing from evidence against what someone believes usually only reinforces that belief, or pushes the person you’re trying to convince to seek community support from people who will reinforce their challenged beliefs. That’s the Backfire Effect, though it should be noted that there’s a lot of churn and dispute about how powerful the backfire effect really is. It’s emotions that impact belief much, much more. You need to speak to how people feel, first and foremost.

Let’s say, as an example, you want to argue against trans sports bans. A cis audience who doesn’t have trans folks in the family probably won’t be convinced by you giving them data from research that says that trans women are at a disadvantage against cis women in sports, no matter how reliable that data is. On the other hand, asking a mother how the bans will be enforced, and what might happen if her daughter gets accused of being trans just because she’s good at softball? Talking about how she could get forced to have her little girl’s private parts inspected—something that’s absolutely reprehensible and completely indefensible, and which has already happened many times?

That’s much more likely to persuade.

It’s not that your audience doesn’t care about trans people, which is what you hear a lot within the trans echo chamber. It’s the basic principle why Medicaid is much more poorly run than Medicare in America: a program for the poor is a poor program. Medicaid helps people down on their luck. Medicare is for everyone who’s old enough. People care about themselves and their families before they care about their friends or even strangers, so the best arguments, and the best policies, are the ones who help and apply to everyone.

Finding your moment—Kairos

There are moments that are more important than others, for any given thing, ideal, dream, or impending disaster. Maybe the best example right now is the danger that Project 2025, and Trump’s promises of going fully fascist, pose to not just the US, but global stability (sorry for the specific politics, but this is an article about activism). To be frank, it doesn’t matter what you want, politically—if you’re reading this newsletter, you won’t get it, and probably won’t ever even have a chance to get it, if he gets elected, whether your issue is justice for the Palestinian genocide, access to equitable healthcare, or equal rights for trans folks.

In other words, there are times to stand on principle, to help build a more just and equitable future even if it hurts in the short term. Right now? It’s not one of those times. The other folks are fighting to upend the whole system so you won’t be able to ever again.

In a nutshell, paying attention to the context an argument is within means you need to look at the big picture of how the specific thing you care about fits into the wider rhetorical situation, so you can understand what things are pressing on your audience. If they’re worried about being able to pay for groceries, or how understaffed they are at work, they’re not going to care so much about things that don’t speak to those realities. The response you’ll get will be something on the order of “you’re right, but I’ve got bigger fish to fry right now.”

You’ve won… but it doesn’t matter.

Speaking to the greater context at a time like this can be one of the really tough parts, because everyone’s under pressure these days, and we’re all kinda doing our best to hold our families together. Thing is, it’s also why it matters, and with some careful thought, it can also be a real advantage.

Let’s say you want to persuade someone to support transition healthcare, and they don’t feel like they should have to pay for what they see as “cosmetic stuff,” because their health insurance is already as expensive as they can afford. Well, trans folks say again and again that gender-affirming care is for cis people too, but that means that there’s an opportunity to argue to that guy that the testosterone he takes for low T is the same stuff you want to protect and expand trans peoples’ access to—and that if he gets his way, he’ll have to pay hundreds of dollars more every month for his own meds. That it’s really important to protect that right now, because these bills to exclude it are bring brought up right now; if he waits, he’ll be stuck with the extra bills, and there’ll be nothing he can do about it.

A lot of people don’t really think through the implications of their own positions. The right word at the right moment can change that. To be able to deliver that right word, you need to know all the different ones it can be, so to speak.

Parts of a whole

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ve probably noticed a theme throughout the four constituents of the rhetorical situation: as a rhetor? The argument can’t be about you. If it’s about you, you’re playing defense, and you’re probably gonna lose.

A good persuasive argument is about the person you’re making the argument to, first, last, and everything in between. That’s tricky when you’re trans, and trying to protect yourself and your community.

At the same time, though, that same sense of community is also where you can start making a bigger difference. If you’re arguing all by yourself, you’re going to have a damn hard time making meaningful progress. You’re not alone, though—there are many advocacy groups near you who you can get involved with, whether it’s a political party or a nonprofit, and they can help you make a much bigger impact. Sometimes, that support is financial first—there’s a reason I talk up the ACLU in the US, and you can probably guess where a chunk of my activism budget goes. Sometimes an organization needs boots on the ground, even if all that means is picking up boxes of yard signs and handing them out to people. It can feel like scut work, but you’re new and learning how to be effective.

You’re not going to join any organization in a leadership role, and that’s a good thing. People entering without experience and know-how is how preventable disasters happen.

When you step into those roles, remember to work on your active listening and pick up on the things that make a difference. Remember that compromise (with our allies—people who are arguing and working in good faith toward a better tomorrow) is how we move the needle, and moral perfectionism is how we end up with nothing but a smug sense of self-righteousness. Never let the perfect be the enemy of the good, or the better.

Listen especially to leaders who’ve been at these fights, and those like them, for a long, long time. Black and Brown organizers and leaders in particular generally have an incredible wealth of experience, and if you’re anywhere near as white as I am, you haven’t even been thinking seriously about equity and social justice for as long as they’ve been right there on the front lines, trying to make a difference in a fight you’re just joining in earnest now.

We can win. We will win.

But it won’t be overnight.

I feel like I'm stuck between the ol' rock and hard place. I want to help fight the good fight, but I've already rocked the boat quite a bit lately.

Context: I'm a public HS Math teacher in the south, for my own health I finally made the leap to be my authentic self in all my domains. My admin and coworkers support me but I know that there's some parents/students who aren't a fan (as evidenced by my roster total going from 100 before open house to 75 on 1st day, likely not all my doing, but too many to not have a correlation).

I don't want my presence to go unnoticed, but my admin team basically said to keep my head down and just teach the math. It's difficult for me to find the fine line of keeping my current job intact (I don't get tenure for 2 more years) and making my presence known to those who's minds can be swayed off the fence.

Thanks for another fantastic piece to push me out of my comfort zone (assuming that a trans person can ever have a comfort zone).

Editing question. First sentence, "word" or "world?"